Alaska Volcano Blanketed Europe with Ash 1,200 Years Ago

Alaska's Mount Churchill volcano erupted some 1,200 years ago, spreading ash from Canada to Germany. The incredible reach resembles a high-school hitter powering past Babe Ruth's prodigious home run records.

"It's a bit surprising, because we wouldn't have expected an eruption of this magnitude to have ash go this far," said lead study author Britta Jensen, a geologist at Queen's University in Belfast, Ireland.

Only one other eruption in the last 2 million years has covered the Earth with an ash layer that traveled 4,350 miles (7,000 kilometers) — the Toba supervolcano. Toba was a colossal super-eruption that threw out 670 cubic miles (2,800 cubic km) of ash, smothering South Asia, India and East Africa 75,000 years ago. "Toba was a monster. It was truly a huge eruption," Jensen said. [Big Blasts: History's 10 Most Destructive Volcanoes]

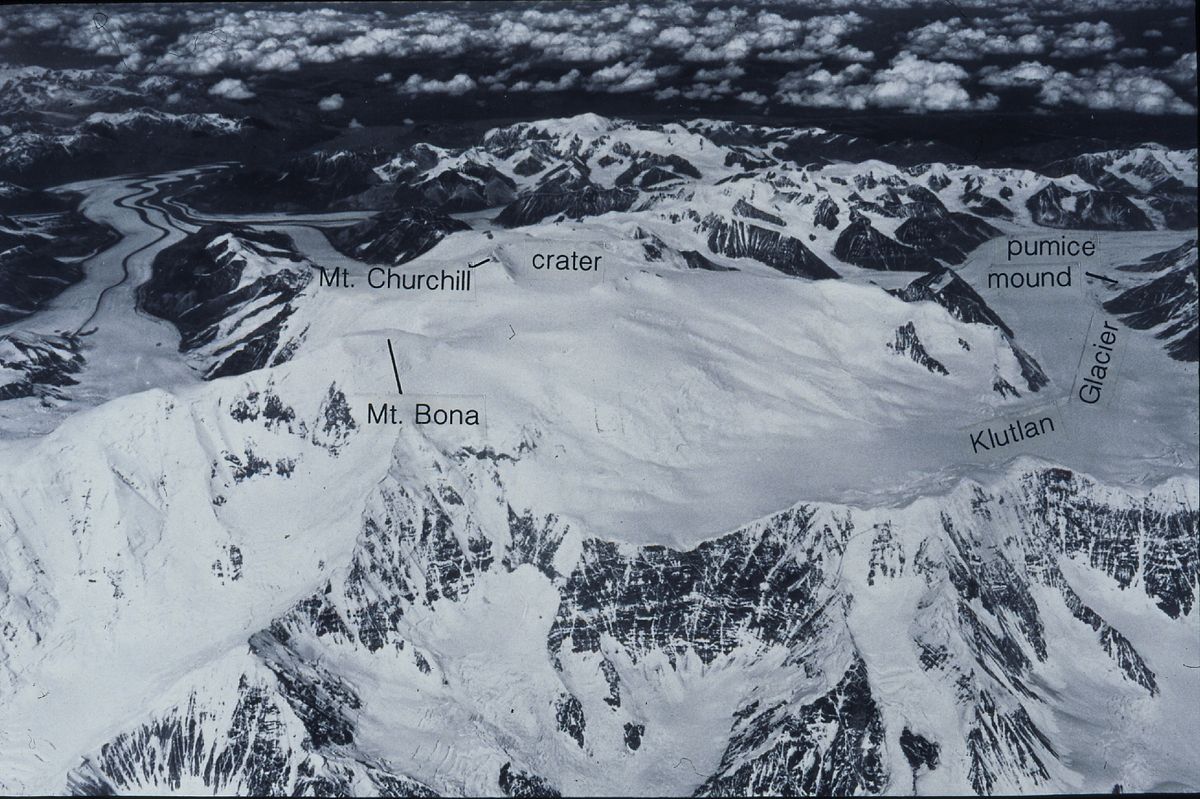

Mount Churchill is also an impressive volcano, the tallest on land in the United States and one of the towering, snowy peaks of Alaska's Wrangell-St. Elias Mountains. But Churchill's blast in A.D. 843 ejected just 12 cubic miles (50 cubic km) of ash, a layer now called the White River Ash, according to the new study, published in the September 2014 issue of the journal Geology. And the eruption hit just 6 on the Volcano Explosivity Index (VEI) scale, two ranks below Toba's VEI of 8 but larger than Mount Pinatubo's 1991 eruption, also a VEI of 6, according to Jensen. (Each VEI step is a 10-fold increase in explosivity.)

"It's pretty exciting and a little concerning if you think about hazards," Jensen told Live Science.

If moderate volcanic eruptions can spread ash for thousands of miles, then these blowouts may be more hazardous than scientists think. "If there was an eruption in western North America close to the size of White River, the potential impact would be enormous," Jensen said. "You could potentially shut down the air space across North America, the Atlantic and Northern Europe."

The good news is volcanic eruptions of Mount Churchill's size strike only once every 100 years, on average. "When you think about, we've been really lucky," Jensen said "We've been flying for the last 50 years, and nothing like [White River] has really happened. The lesson here is that by identifying this, we can start to think about what kind of impact that would have on our society."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cryptic clues

The White River discovery also means scientists may start hunting for the origin of mysterious volcanic shards on other continents, instead of close to home. Volcanic ash is a valuable time marker in diverse fields, from climate change to paleontology — as long as the tiny fragments can be linked to a source. For example, some archaeologically important ash layers in Central America have never been tied to a specific eruption.

"I really do think that the only reason we haven't seen more examples of far-traveled ash like this is because we haven't looked," Jensen said.

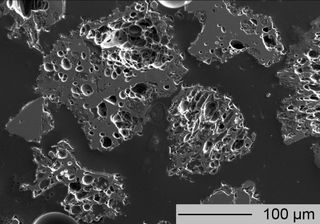

By the time the White River ash crossed the Atlantic, it was simply a few sprinkles of microscopic glass shards, not a thick, hefty layer as in Canada's Yukon Territory, where Jensen works. The elusive grains are called cryptotephra, and are invisible to the naked eye. The White River cryptotephra were small and light enough that high-altitude winds could whisk the shards across the Northern Hemisphere.

"It's just the most incredible, frothy pumice. It's just full of holes," Jensen said. For decades, researchers in Europe have relied on tephra, from Iceland and elsewhere, to help correlate and date peat bog sequences.

No volcanic eruption in Europe ever matched the enigmatic tephra that Jensen and her colleagues connected to Mount Churchill, which was dubbed AD860B in Europe. It took nearly 20 years before study co-author Sean Pyne-O'Donnell, also at Queen's University, discovered the right clue in a Newfoundland, Canada, peat bog.

At first, Pyne-O'Donnell thought the bog would hold Iceland ash, because Newfoundland is closer to the Atlantic island of Iceland than to the Pacific's ring of fire. But the bog instead held ash from Mount Churchill, Mount Mazama (Crater Lake) in Oregon, Mount St. Helens (Washington), and Alaska's Mount Augustine and Mount Aniakchak. The findings were the first step in connecting the White River Ash to Europe's cryptic AD860B tephra.

"For some of these unknowns that we could never identify, we really need to start looking further afield," Jensen said.

Connecting the dots

The good news for geologists who must now search the planet for ash progenitors is that every volcano births a unique set of shards. The tiny particles not only vary among different volcanoes, they even vary between eruptions in the same volcano, with distinct shapes and amounts of chemical elements. The White River ash, for example, has a relatively high chlorine content.

Altogether, these traits act like "fingerprints" to distinguish ash layers that may seem identical to the naked eye. And there is, in fact, a worldwide volcanic ash database, akin to the criminal fingerprint database maintained by law enforcement. [Volcano Ash: Shape Matters | Video]

Jensen and her colleagues have now picked out the White River ash bogs and ice from Nova Scotia, Greenland and sites across northern Europe, including Ireland, Scotland, Norway and Germany.

The layers precede, by about 50 years, a warm, dry period called the Medieval Climate Anomaly. The eruption could help climate change researchers tie together the various records of the changes that led to this climate swing, and determine whether the shift occurred simultaneously across the globe or began at different times in different places, Jensen said. (The volcanic ash itself had little to no cooling impact on global climate, according to historical records.)

"It's just so useful to have this incredibly large region connected by this ash bed. It's a perfect tie line," Jensen said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.