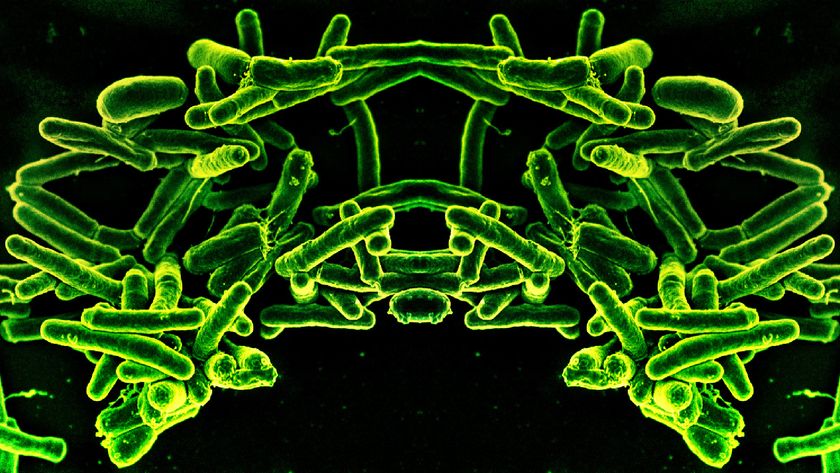

E. Coli Outbreak Linked to Dirty Medical Equipment

A recent outbreak of a deadly strain of E. coli in an Illinois hospital was spread by contaminated medical equipment used to examine patients' intestines, according to a new study.

In 2013, nearly 40 patients at the hospital were infected with a strain of E. coli called the New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-producing strain, or NDM-producing strain. No patients died as a direct result of the outbreak.

The NDM enzyme made by this strain of bacteria breaks down antibiotics, making the infection very difficult — if not impossible — to treat, said Dr. J. Todd Weber, chief of the prevention and response branch in the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which launched an investigation into the outbreak.

The CDC officials reviewed the medical backgrounds and hospital records of the first six patients to become infected with the deadly strain, and found that all of them had previously undergone procedures called endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographies (ERCPs). Doctors perform these procedures to diagnose and treat problems in the bile, pancreatic ducts and other parts of the intestine. [Body Bugs: 5 Surprising Facts About Your Microbiome]

The procedures are done with a type of endoscope called a duodenoscope. This long, tubelike piece of equipment has a camera at one end that's inserted through the mouth of the patient, into the stomach and finally into the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. Unlike the simple endoscopes used to perform colonoscopies, duodenoscopes have a more complex design and include a feature within them called an elevator channel, said William Rutala, director of the statewide program for infection control and epidemiology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, who was not involved in the CDC's investigation.

The channel helps keep guidewires and catheters in the correct place during the procedure. "This channel is complex in design and may be more difficult to disinfect completely," Rutala told Live Science in an email.

There have been a number of past outbreaks associated with duodenoscopes, and the investigations of those outbreaks determined that the scopes hadn't been disinfected properly, Weber said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But that was not the case in the most recent E. coli outbreak in Illinois, Weber told Live Science.

The hospital where the outbreak occurred was following proper protocol, CDC researchers concluded in their study. They had used the manufacturer-recommended disinfection method known as automated high-level disinfection with a chemical called ortho-phthalaldehyde (OPA), Rutala said.

This type of disinfection, with liquid chemicals, has been the preferred method of cleaning endoscopes because it doesn't require high temperatures, which might damage the devices, and it's approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Rutala said.

However, this method was clearly not sufficient to kill all the bacteria contaminating the scopes, a point that CDC researchers pointed out in their study. Since the outbreak, the hospital changed its protocol and now sterilizes its endoscopes with ethylene oxide gas, Weber said.

Sterilization is a more rigorous cleaning procedure than disinfection with liquid chemicals and might have helped prevent the recent outbreak, according to the researchers. However, a switch to sterilization might not be a possibility for all facilities that use duodenoscopes.

For one thing, the gas sterilization process takes longer than conventional disinfection methods, and the gaseous chemicals used in the cleaning process can be toxic. Furthermore, some types of gas sterilization aren't compatible with endoscope devices, according to CDC researchers.

The sterilization method currently in use by the hospital in Illinois is also not FDA approved, according to Rutala. New endoscope-sterilizing technologies will need to be developed and gain FDA approval to help prevent such outbreaks from occurring in the future, Rutala said.

In January, the CDC put out a notice to doctors to inform them about the risk of exposure to E. coli through duodenoscopes, Weber said. But manufacturers, as well as the FDA, will need to get involved to ensure that the bacteria aren't being spread through these devices in the future, he added.

The CDC's case study, as well as an editorial by Rutala, were published today (Oct. 7) in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Elizabeth is a former Live Science associate editor and current director of audience development at the Chamber of Commerce. She graduated with a bachelor of arts degree from George Washington University. Elizabeth has traveled throughout the Americas, studying political systems and indigenous cultures and teaching English to students of all ages.