In photos: The world's oldest cave art

Archaeologists may have discovered Earth's oldest known cave art. Dating back to around 40,000 years ago, paintings in Indonesian caves of human hands and pig-deer may be the oldest ever found — or, at the very least, comparable in age to cave art in Europe. Here's a look at the rock art, discovered and dated from seven caves sites in Sulawesi, an island of Indonesia. [Read full story on the Indonesia cave art]

The paintings were found decades ago in Indonesia's Maros and Pangkep regions, which have cave-dotted karst rock formations. But the artwork was only recently dated, revealing that the paintings are much older than was previously assumed. The finding sheds light on early human creativity and representational art. CREDIT: Screengrab, Nature Video.

The Maros karsts, in southwest Sulawesi, have dozens of caves. In addition to paintings, archaeologists have found other traces of human occupation inside these cavers: ochre "crayons," animal bones and shells. CREDIT: Anthony Dosseto.

One hand stencil found in this region has a minimum age of more than 39,000 years old, said Maxime Aubert, of Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia, in a video about the finding. "This is the oldest hand stencil in the world," Aubert added in the video. CREDIT: Kinez Riza.

Hand stencils, like the ones shown here, are created when artists spray paint or pigment over their hands. Similar hand stencils were found in El Castillo cave in northern Spain, but they are younger, dating back to 37,300 years. CREDIT: Kinez Riza.

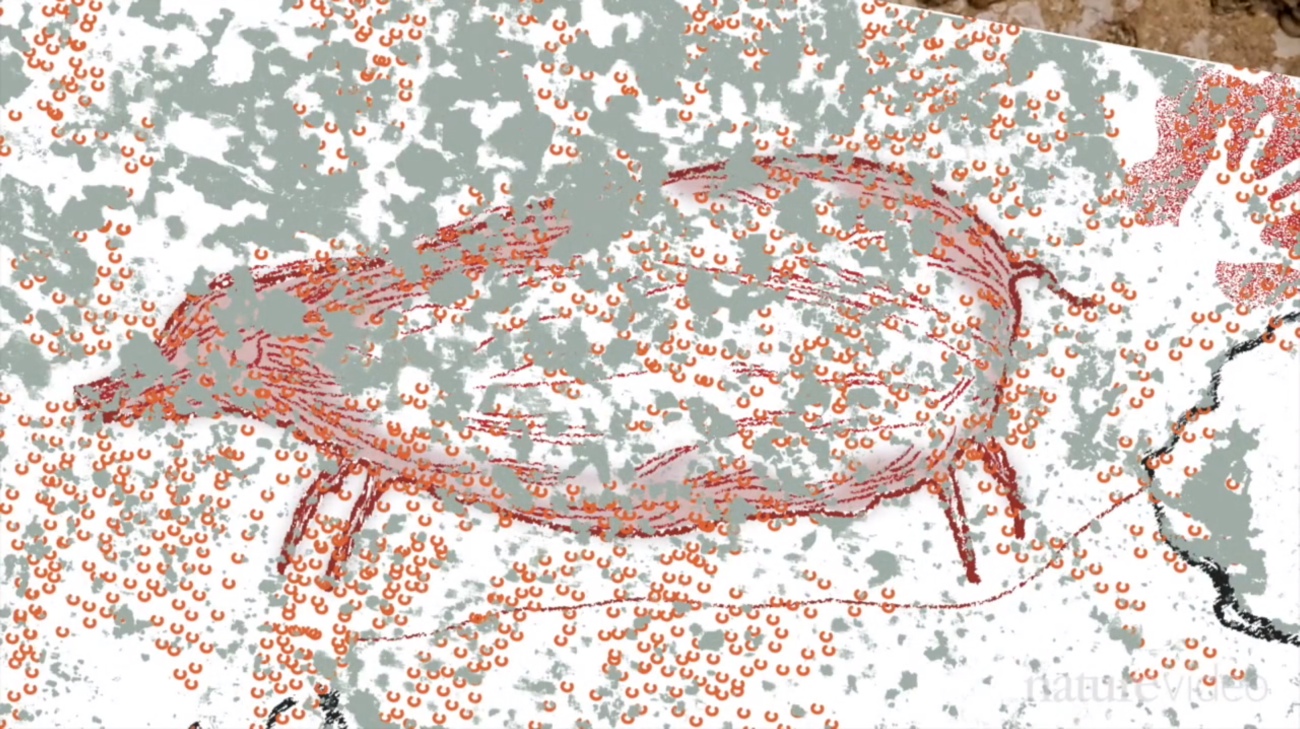

The new research suggests that humans were painting murals on the ceilings and walls of their caves in Indonesia at the same time as people in Europe. Only remnants of such artwork remain. This painting of fruit-eating pig-deer, known as a babirusa, was discovered in an Indonesian cave and dates back around 35,400 years ago. CREDIT: Screengrab, Nature Video.

The animal paintings inside Chauvet Cave in France were thought to be the oldest known examples of figurative art in the world. But the pig-deers, miniature buffalos and other creatures depicted by prehistoric artists in Indonesia could change that narrative. CREDIT: Kinez Riza.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's not clear if humans already had artistic instincts by the time the left Africa to colonize parts of Eurasia 100,000 years ago, or if symbolic representation arose independently in far-flung parts of the globe. CREDIT: Anthony Dosseto.

"In the early 1980s there were a lot of cave paintings on this site in the form of hand stencils (shown here)," said Muhammad Ramli, of the Preservation of Cultural Reserves Association in Indonesia, as translated in a Nature video, referring to the new finding. "Now a lot has been damaged through exfoliation, pieces falling off. And others are covered by calcium carbonate." CREDIT: Screengrab, Nature Video.

These calcium carbonate deposits, which can take the form of "cave popcorn" (shown here) contain radioactive uranium. That radioactive element provided a way for scientists to date the cave art. By dating the layer of "popcorn" on top of the art, the scientists came up with a minimum age and the date for the layer beneath the painting revealed the art's maximum age, the researchers said. CREDIT: Screengrab, Nature Video.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.