How the Violin Got Its Shape

The elegant shape of the violin evolved over a period of 400 years, largely due to the influence of four prominent families of instrument makers, a new study finds.

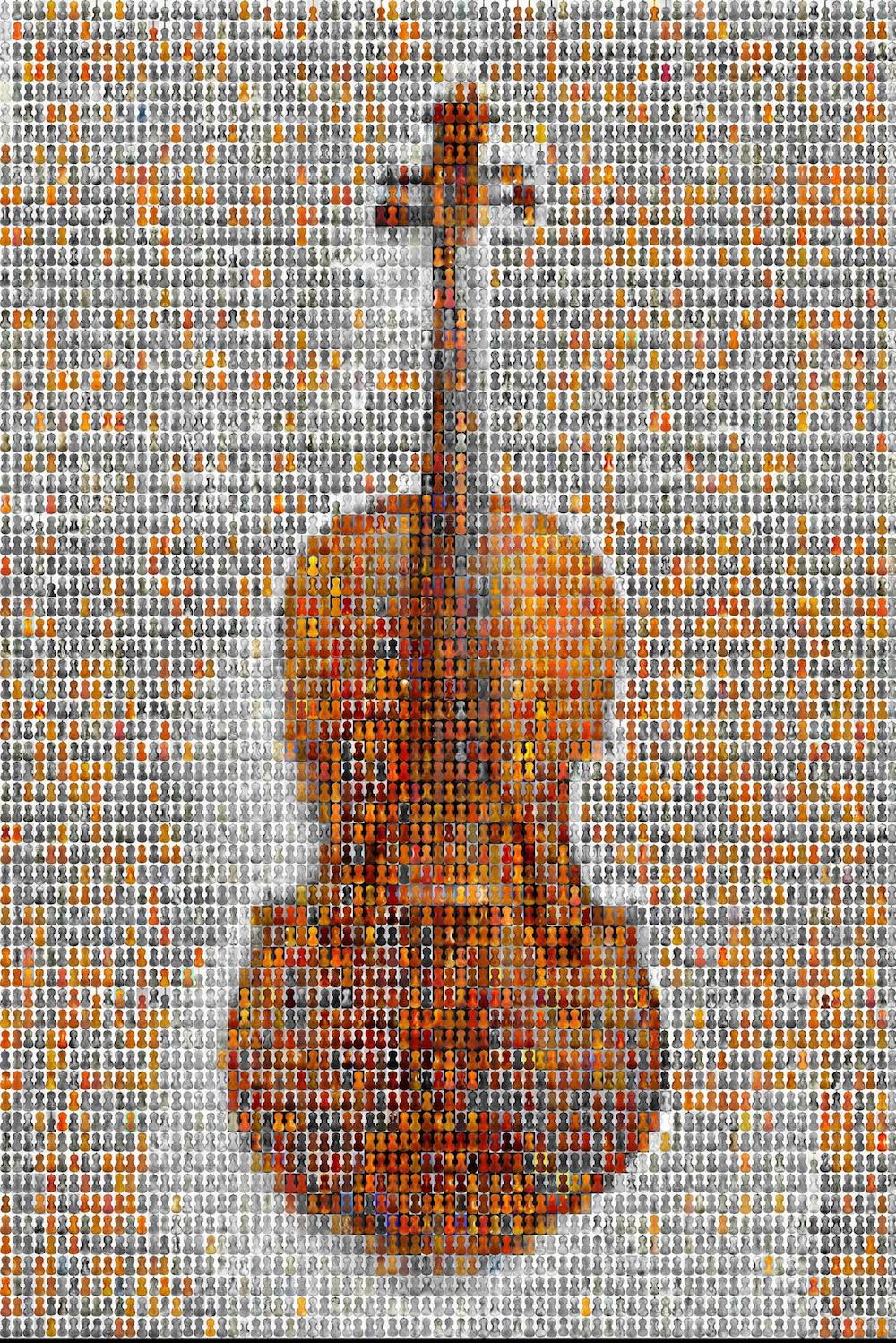

Researchers analyzed more than 9,000 violins, violas, cellos and double basses, and found that the shape of violins depended on the makers' family background, country of origin, the time period in which it was constructed, and how precisely the violins imitated the greats, such as the stringed instruments expertly crafted by Antonio Stradivari.

The first violins were made in Italy in the 16th century. Stradivari, one of history's most respected violin makers, lived in Cremona, in northern Italy, from 1644 to 1737. He crafted roughly 1,000 violins, including about 650 that have survived to this day. [In Images: Recreating a Legendary Stradivarius Violin]

In fact, the study found that the shape of modern violins has been disproportionately influenced by the work of Stradivari, said study researcher Daniel Chitwood, a scientist at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center in St. Louis.

"It's so well documented that there are violin makers who openly said they were copying Stradivari because his violin shapes were more desirable," Chitwood said.

Chitwood isn't a master violin maker; he's a plant researcher who studies developmental genetics but also plays viola in his spare time. He typically studies how plant genetics relate to the shapes of leaves.

In the new study, he used similar techniques to examine how the "traits" of violins, or their shapes, changed over time. "Really, violins are just a trait of human beings, just as plants have a trait," Chitwood told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some imitations are so exact that, in a separate study pitting new violins against the ones of the old masters, expert violin soloists could not distinguish between old and new violins. The soloists also preferred the new violins to the old ones, surprising musicians everywhere, the study, published in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found.

"[Stradivarius] are exceptional violins, but they're not always the best violin," Chitwood said.

When and where a violin was made also factored heavily into the instrument's shape. "These people couldn't help but be born in Cremona, or Paris or London," Chitwood said. "The instruments that they produced were shaped by where they were in history and where they were at."

Violin making also tended to be a family business passed down through the generations, so "human relatedness was also contributing to the different violin shapes throughout history," Chitwood added. For instance, the brothers Nicolò and Gennaro Gagliano, who lived in Italy during the 1700s, made similarly shaped violins.

To assess the evolution of violin shapes, Chitwood relied on images from online sales of rare and valuable violins. By analyzing the outlines of the instruments, Chitwood found four main "blueprints" influenced by master instrument-making families, including Stradivari, the Italian Giovanni Paolo Maggini (1580-1630), the Italian Amati family and the Austrian Jacob Stainer (1617-1683). [Creative Genius: The World's Greatest Minds]

While examining the outlines of violins, Chitwood also found that using his analysis, the shape of a viola is indistinguishable from that of a violin about 63 percent of the time. A viola player himself, Chitwood said the instrument should probably be larger to accommodate its deeper range but that instrument makers decided to limit its size so that it could be played under the chin, like a violin, instead of between the legs, like a cello.

If made any larger, the viola would likely cause backaches in many viola players, he said.

"We wrongly decided that we're going to put them under our chin," Chitwood said. "But the real solution is that we should be playing violas between our knees."

Shape and sound

"This study looks at evolutionary patterns in that outline over the centuries," said Jim Woodhouse, a professor of engineering at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the study. "It reveals some fairly clear trends, and also clear clusters of related shapes."

The arching patterns and thickness of the wood used to make a violin's plates, as well as the plates' wood properties, are vital to the instrument's acoustics. In contrast, the shape of a violin doesn't have a strong influence over its sound, which means crafters can experiment with how they construct the body of the instrument.

"As the author [of the new study] acknowledges, outline shape has not received a lot of attention from scientists looking into the physics of how the violin works," Woodhouse said. "This is not an omission; it is based on a clear expectation that outline shape probably has a rather minor importance to sound. Other aspects of the violin structure are far more important."

Violin aficionados interested in Chitwood's work can download a poster of the violin images used in the study.

The findings were published today (Oct. 8) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.