Where Is El Nino? And Why Do We Care?

That El Niño we’ve been tracking for months on end — the one that is taking its sweet time to form — still hasn’t emerged, forecasters announced Thursday.

But the reason we still care so much about it, following all of its tiny fluctuations toward becoming a full-blown El Niño, is that it can have important effects on the world’s weather, including in the U.S. It can even boost global temperatures, helping set the planet on the course to be the warmest year on record.

In their monthly update, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society at Columbia University said there is still a two-thirds chance that a weak El Niño event emerges and that it will likely do so in the October-to-December timeframe, lasting until spring 2015.

“I think it’s pretty safe to say that we’re essentially taking one step forward, that is one month forward since last month,” CPC forecaster Michelle L’Heureux told Climate Central.

How Will We Know When El Niño Finally Arrives? Struggling El Niño Still Shaping Hurricane Activity Why Do We Care So Much About El Niño?

While the conditions that mark an El Niño — such as warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific and a reversal of prevailing winds in the region — haven’t fully gotten in synch, they still can, and in some cases are, impacting the global climate and weather.

There’s a robust connection between El Niños and quiet Atlantic hurricane seasons, which the 2014 season has turned out to be, and hurricane experts have said that the burgeoning El Niño is part of the reason.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Even though waters in the eastern and central parts of the tropical Pacific haven’t consistently been warm enough to herald an El Niño, they are still affecting the atmosphere in a way that creates more stable, subsiding air over the Atlantic and more wind shear. Both of those factors tamp down on hurricane formation and development.

“This is fairly typical in fall” when the system is leaning toward El Niño conditions, L’Heureux said.

Those warmer waters, particularly ones in the central tropical Pacific, also helped bump this past summer into the books as the warmest summer on record. That heat has put 2014 on the path to possibly becoming the warmest year on record. If the El Niño continues to develop and forms before the end of the year, it will help nudge the planet toward that record.

The story isn’t quite the same for other El Niño impacts, namely the connection to a wet winter in Southern California. Only strong El Niños are associated with above-average winter precipitation there, something the region desperately needs in the midst of a three-year drought that is one of the most intense in the state’s history. But with this El Niño expected to be a weak one, the picture for California’s winter is unclear right now.

“We can’t rule anything out,” L’Heureux said.

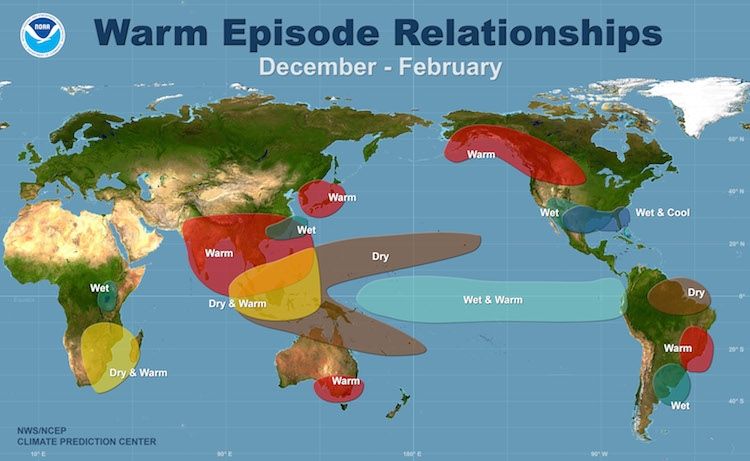

Other areas also see their precipitation affected by an El Niño, particularly in the Northern Hemisphere winter, with Indonesia and northeastern South America tending toward drier-than-normal conditions, for example. Places like Southeast Asia and northwestern North America tend to see warmer-than-normal temperatures. Those impacts can in turn affect agriculture, by bringing too much or too little rainfall to crops, as well as public health, by, for example, reinforcing the conditions in which mosquitoes that spread malaria breed.

Just as the exact impacts depend on how strong an El Niño is, they can also depend on its timing, both when it fully forms and when it peaks.

The expected start time for this El Niño is on the later end of the typical timescales for such events to emerge, but not unprecedented.

“There is a very wide range of start times,” L’Heureux said. “Anywhere from April to the end of the year.”

If the El Niño arose in the late fall, but then began to decay quickly, in January or February, then some of the typical impacts seen in the U.S. would be affected because they don’t typically emerge until the January-to-March timeframe.

“We do need the El Niño forcing to persist,” L’Heureux said.

L’Heureux and her fellow forecasters expect this El Niño to persist into the spring, but nothing is certain when it comes to El Niño. The record of at least fairly reliable sea surface temperature records extends back only to 1950. With such a relatively short record, El Niño researchers don’t think they have seen all the varieties of El Niño that can form, both in terms of onset and strength.

“We haven’t observed all that we can observe,” L’Heureux said. “So it’s not just what we know, but what don’t we know about El Niño evolution.”

You May Also Like: 2014 Extreme Weather: What Attribution Can Tell Us Sea Level Rise Making Floods Routine for Coastal Cities Oceans Getting Hotter Than Anybody Realized Antarctic Sea Ice Officially Hits New Record Maximum

Follow the author on Twitter @AndreaTWeather or @ClimateCentral. We're also on Facebook & other social networks. Original article on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.