New Diabetes Drug Is Activated with Light

A new drug for type 2 diabetes could be activated exactly when it's needed by shining a blue light on the skin, and might one day give patients with the disease more control over their blood sugar levels, some researchers say.

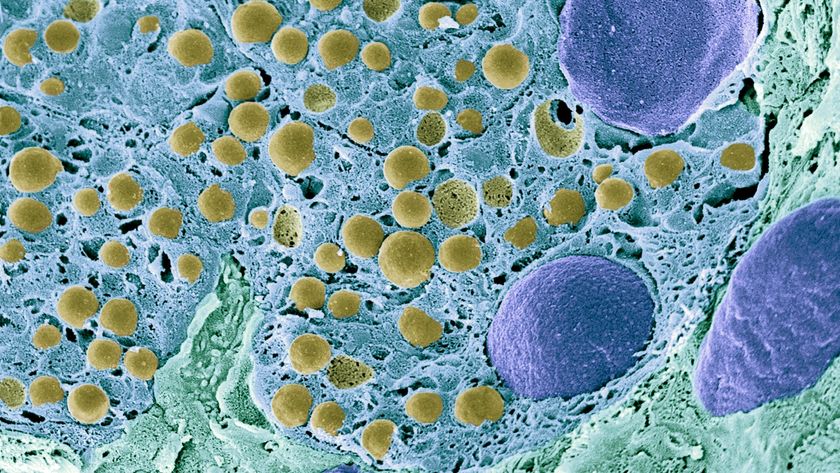

In a new study, researchers adapted an existing diabetes drug so that it is active only when it is exposed to blue light. Once active, the drug was able to stimulate the release of the hormone insulin from pancreatic cells in a lab dish, the study found. (In people with type 2 diabetes, insulin doesn't work normally, or is not produced in sufficient amounts, which leads to high blood sugar levels.)

Because the study involved only cells in a lab dish, there's a long way to go before a treatment based on this drug could be available to patients, said study researcher Dr. David Hodson, of the Department of Medicine at Imperial College London in the United Kingdom. But in theory, patients could swallow such a drug, and when they need it, they could shine a blue light on their abdomen to activate the drug within the pancreas, the researchers said.

Only a small amount of blue light is needed, and the drug becomes inactive once the light is turned off, they said. [5 Diets That Fight Diseases]

"In principle, this type of therapy may allow better control over blood sugar levels because it can be switched on for a short time when required after a meal," Hodson said in a statement. "It should also reduce complications by targeting drug activity to where it's needed, in the pancreas."

Currently, some drugs for type 2 diabetes can cause side effects because they act on other organs, such as the brain and the heart, and they can sometimes stimulate the release of too much insulin.

"Work on light-activated medications is still at a relatively early stage," Dr. Richard Elliott, from Diabetes UK, a charity organization that funded the study, said in a statement. "But this is, nevertheless, a fascinating area of study that, with further research, could help to produce a safer, more tightly controllable version" of diabetes therapies, Elliott said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study is published today (Oct. 14) in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. FollowLive Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.