Eyeless Swimmer: Bizarre Primitive Animal Is Your Cousin

Newfound fossils may solve a century-long mystery over the identity of a bizarre 500-million-year-old animal.

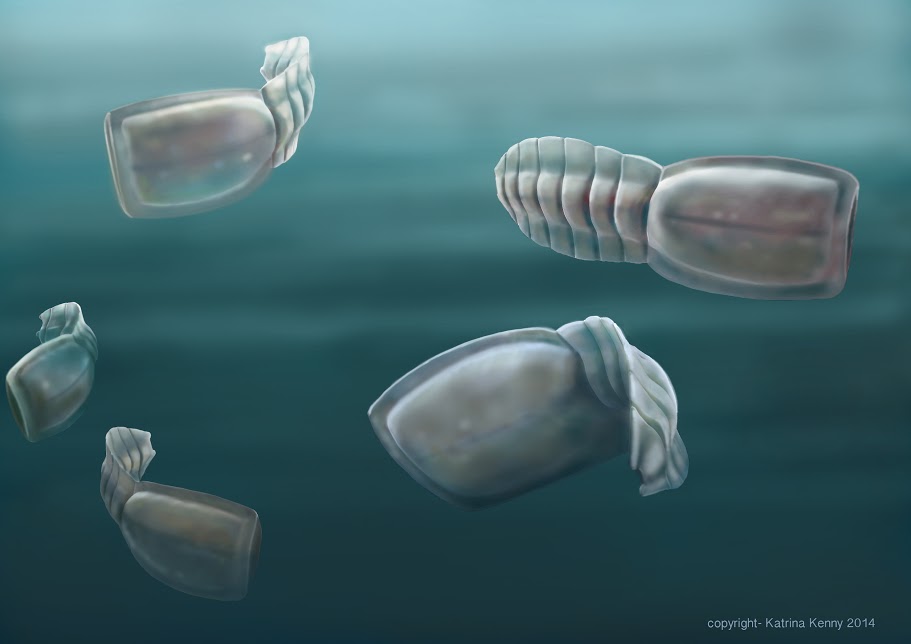

Strange figure-8 shaped creatures from the Cambrian Period are actually very distant cousins of humans, according to a new study. These vetulicolians, as they are known, appear to have possessed a notochord, a hollow nerve structure — just like modern vertebrates, including humans.

"It finally puts to rest the position of this weird-looking group of animals," study researcher Diego Garcia-Bellido, an invertebrate paleontologist at the University of Adelaide in Australia and an honorary research associate at the South Australian Museum, wrote in an email to Live Science. The findings also suggest that chordates, or creatures with notochords, were diverse and successful from the beginning of animal evolution, he said. [Gallery: See Images of the Bizarre Swimming Animals]

Weird life

Vetulicolians were truly bizarre: They lacked eyes, but had a wide mouth and a segmented tail. Like miniature whale sharks, these early animals swam through the oceans, filter-feeding off plankton and other microscopic tasties. Fourteen species have been found in the fossil record since 1911, including specimens from Greenland, southern China and western Canada.

Now, Garcia-Bellido's team has discovered a new species of this group on Kangaroo Island, Australia, a hotspot for Cambrian-age fossils with soft parts like musclesand guts preserved in stone. They dubbed their find Nesonektris aldridgei. "Nesonektris" is the Greek word for "island swimmer," while "aldridgei" honors late University of Leicester geologist Dick Aldridge, who studied vetulicolians extensively.

The most complete specimen of the new species measures about 4.9 inches (12.5 centimeters) long; most of the 150 or so fossils the researchers found were fragmented into tails and bodies, with tails usually measuring around 3.5 in. (9 cm) long. It was in these tails that the researchers noticed something very strange.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Running through the tails were long, rodlike structures. They might have been part of the gut, but they were unusually long and wide, the researchers reported in September in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology. More mysteriously, the rods appeared segmented into strange block-shaped structures.

"This finding is inconsistent with it being a gut (which is a hollow tube), but consistent with the way a cartilage (notochord) would break, which allowed us to realize where the group might belong in the tree of life," Garcia-Bellido said.

Tied by a chord

Notochords are present in the embryos of all vertebrates, acting as a cartilaginous sort of skeletal support before the bones form. Some boneless invertebrates, including filter-feeding sea squirts, retain the notochord throughout life. All animals with notochords (vertebrates included) are called chordates.

By comparing the Kangaroo Island fossils with animals such as sea stars, sea squirts, jellyfishlike salps and vertebrates, the researchers were able to position the vetulicolians as close relatives of tunicates, a group made up of sea squirts and salps. This puts vetulicolians in the same chordate category as vertebrates, including humans — not humans' direct ancestors, Garcia-Bellido said, but "cousins."

Paleontologists will need to re-evaluate other vetulicolian species in search of notochords, Garcia-Bellido said. The ultimate goal is to reconstruct the family tree of some of the first animals ever to evolve.

"On our part, we will continue to excavate the [Kangaroo Island] locality, searching for more clues about the oldest animals in the world," he said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.