Bugs as Treatment: Coming to a Clinic Near You... (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. The publication contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

When you’re sick, you want the most effective treatment to help get you back on your feet. But what if that involved bugs?

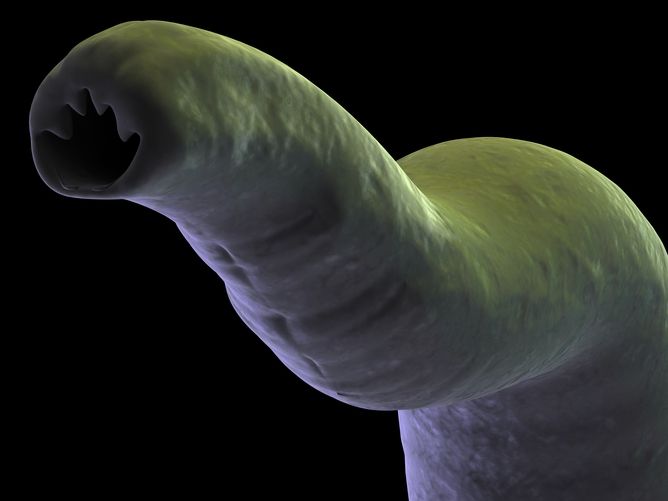

Maggots and leeches have been used for decades and are still supplied to hospitals for speciality treatments. Researchers are now investigating whether hookworms can allow people with coeliac disease to safely consume wheat.

Leeches and maggots

Creepy crawlies have long been used for various types of treatment. Historical references from ancient Greece show that leeches were used as far back as 270 BC, probably for bloodletting.

Over the years, leeches have been used for many purposes. With their potent secretions, leeches make microsurgery or plastic surgery more successful by preventing venous blood from collecting.

The modern story of the maggot in wound healing is that one fortunate solder in the First World War was found to have survived a life-threatening wound apparently because it was covered with maggots. The maggots ate the dead and dying flesh and helped to keep the wound from becoming fatally infected.

Today, wound healing is still an issue where modern medicine is not available, or where conventional therapies are ineffective, as with Bairnsdale Ulcer (Buruli ulcer) in Victoria, Australia, where “mighty maggots” are being trialled as a better treatment.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Although maggots are still used in some hospitals today, your chances of having a typical wound heal with or without maggots is about the same.

Worms and bacteria

Researchers first noticed that parasitic infection reduced the symptoms of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) in the 1980s and it’s now an area of active research. At the time, the researchers didn’t know why this would be the case and a number of other factors (such as diet and living conditions) made it difficult to establish a clear cause and effect.

As we learn more about how parasites work, it is becoming obvious that successful parasites came prepared with a full toolbox of chemicals. With the creepy crawlies, these tools do things like thin blood so that the leech – or mozzie – can get a better feed.

In the parasites, they also include molecules which interact directly with the human immune system. A parasite wants to live with you, and to do that it needs to convince your body’s immune system to ignore it.

Parasites that cause chronic infections have evolved ways to manipulate the immune system by switching it from high inflammation and “attack” mode, to low inflammation and “damage control mode”. This switching may have an incidental calming effect on inflammatory diseases like IBD and coeliac disease.

Interestingly, this is a similar argument for why the bacteria H. pylori is good for you in that it may reduce the severity of IBD. But while it could potentially be used as an edible vaccine, the down side is the risk of gastric cancer (in addition to ulcers), so there are good reasons to heed the warning “the only good Helicobacter is a dead Helicobacter”.

Hookworms to treat coeliacs

Coeliac disease is a problem where the body’s immune system attacks fairly innocuous proteins from wheat. This attack also damages the intestine and causes serious problems for sufferers, giving them few options but to avoid gluten altogether.

The immune system attack in coeliac disease is similar to what happens in IBD – ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease – and all three problems are often put together under the general heading of autoimmune diseases.

Michael Mosley ingested a tapeworm for his BBC documentary Michael Mosley.

Recently, the hookworm has been shown to release substances that calm the immune system, allowing the parasite to live peacefully in your gut. This calming effect may be helpful for IBD and recently it has been investigated against coelic disease.

Researchers at Brisbane’s Prince Charles Hospital tested the idea that the immune-calming effect of the hookworm could help people with coeliac disease during a small but well-designed clinical trial. While a previous study had not found an improvement in gluten tolerance, the new study was careful to slowly increase the levels of gluten.

As the researchers point out, the level of increased tolerance achieved was not enough to allow their patients to eat a whole meal of gluten, but it was enough that accidental (or incidental) ingestion of gluten would not cause problems.

Is it worth it?

Maggots secrete a host of factors to dissolve dying tissue. But it’s the actual action of the maggots eating the dying tissues that does the work.

With leeches, they release blood thinners and anaesthetics in a combination that has been difficult to replicate, though I believe this will be possible in the near future.

With parasitic infection of the gut, do you need the actual bug – or could you take a pill containing something that the bug secretes?

A handful of studies have identified molecules with immune-altering effects. But these proteins are “foreign” to the human immune system and may cause inflammation or other problems in own right. So far these molecules are showing promise as vaccines against neglected parasitic infections, but other applications may be some time off.

Personally, I hope these problems can be solved because the alternative – using the whole parasite – is not only distasteful, it also comes with the risk of disease.

Paul Bertrand receives funding from National Health and Medical Research Council for projects relating to gastrointestinal health and disease

Anna Walduck receives funding from RMIT University and NHMRC for research on infectious diseases and immunology.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.