Swimming Mammoths Beat Humans to California

VANCOUVER — A fossil tusk rescued from the sea proves mammoths swam to Southern California's Channel Islands much earlier than thought.

The new fossil is one of two recently discovered tusks that challenge the idea that climate change killed off the Channel Islands' pygmy mammoths, said Daniel Muhs, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Denver, who described the find Sunday (Oct. 19) here at the Geological Society of America's annual meeting. The pint-size beasts disappeared from the islands about 12,000 years ago. Most researchers blame either the Earth's warming climate or the arrival of humans on the islands for the mammoth's demise, he said.

But pygmy mammoths likely survived a steamier, more severe climate swing about 125,000 years ago. "This new find suggests they had to have lived during a period even warmer than the present," Muhs told Live Science. [In Photos: Stunning Mammoth Unearthed in Siberia]

Muhs and his collaborators discovered an 80,000-year-old pygmy mammoth tusk half-buried in the edge of a sea stack on Santa Rosa Island's northwest coast. With a few more storms, the rare fossil — just 3 inches (8 centimeters) wide and 2 feet (62 cm) long — might have disappeared forever into the Pacific, washed out of the rock pedestal. "It was a miracle," Muhs said of the well-timed find. The tusk is now in the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, he said.

Fossil corals buried with the tusk allowed scientists to date the find. But 80,000 years ago, sea level was higher than today. So Muhs said he thinks that mammoths crossed during an earlier glacial period, some 150,000 years ago. "We're going on the assumption that they only swim when the distance [to the mainland] is at a minimum," Muhs said. "Sea level was really low only at 150,000 years ago."

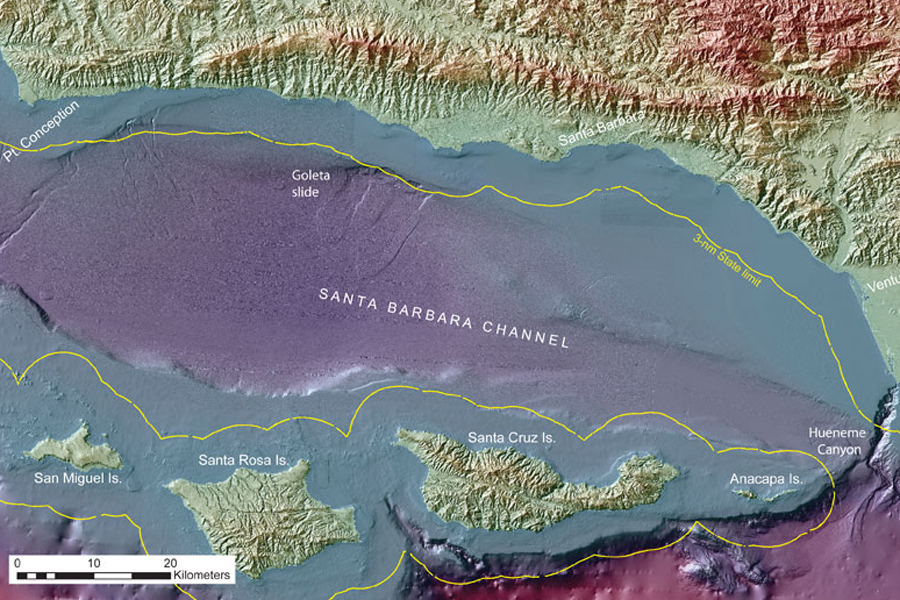

Scientists think mammoths reached the four northern Channel Islands when sea level dropped during past ice ages. At their peak, the planet's giant ice sheets socked away ocean water like sponges, lowering sea level around the Channel Islands nearly 400 feet (120 meters). Twice in the past 150,000 years, when the ice sheets expanded, the islands joined together into one large island, called Santarosae. The distance to the mainland near the city of Oxnard, along the coast of Southern California, shrank to about 4.5 miles (7.2 kilometers), easily reachable by a swimming, 10-ton (9,000 kilograms) Columbian mammoth. The island where the tusks were found, Santa Rosa, now sits about 26 miles (42 km) offshore.

Modern elephants, which share a common ancestor with mammoths, can cover at least 30 miles (48 km) with their ungainly underwater crawl. There are anecdotal reports of elephants swimming to islands in search of food, guided by the scent of ripe fruit.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

During the late Pleistocene epoch, winds blew from the northwest across the islands, carrying the scent of unmunched forests to the mainland.

"Mammoths could have swum over to the Channel Islands several times during different glacial periods, because mammoths have been in North America for 1 million years," Muhs said. However, despite more than a century of searching, no one had found older mammoth fossils on the islands until now.

Recently, Muhs and his collaborators uncovered a second pygmy mammoth tusk from a different rock layer, in sand and landslide deposits. Dating of snail shells with the tusk, and an older marine layer below the sand, reveal that this mammoth died sometime between 46,000 and 100,000 years ago. Even that broad age range is helpful to scientists piecing together the history of these pony-size mammoths.

Until now, researchers had thought the most recent ice age transformed the Channel Islands mammoths into pipsqueaks. That glacial period peaked about 20,000 years ago, and then Earth's climate started to gradually warm.

As the ice sheets melted, sea level rose and trapped the mammoths on separate islands. Once the animals were confined, the competition for a limited food supply favored smaller mammoths, and the animals shrunk until they were half the size of their ancestors. These pygmy mammoths are a unique species, called Mammuthus exilis, found so far only on San Miguel, Santa Rosa and Santa Cruz islands. [6 Extinct Animals That Could Be Brought Back to Life]

"There is every good reason to get small because of reduced forage, and no particularly good reason to stay large, because they've lost the predators," Muhs said. "Fortunately, the big predators do not swim."

Most fossils of pygmy and full-size mammoths discovered so far on the islands are between 20,000 and 12,000 years old, Muhs said. A handful hit 30,000 years old. And one spectacular, 5.5-foot-tall (1.7 m), nearly complete skeleton was uncovered in 1994, dating to about 13,000 years ago.

With the two older tusks, scientists may need to rethink how this textbook example of dwarfism evolved on the island. For example, did the mammoths settle Santarosae 150,000 years ago and then die out before the next ice age? Or did their descendants mix with a new wave of settlers? And what happened when people joined the mix? The earliest human remains overlap with the youngest pygmy mammoth fossils on the Channel Islands, suggesting the first humans arrived just before the mammals went extinct.

"This is one of the coolest fossil stories in the National Parks, which are full of amazing fossil stories," said Jason Kenworthy, a geologist with the National Park Service in Denver who was not involved in the study. "To push the time back and still be finding new information is really exciting. They've added a whole new chapter to the story."

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.