What If Alexander the Great Left His Empire to One Person?

As Alexander the Great lay on his deathbed in 323 B.C., his generals reportedly asked to whom he left his empire. "To the strongest," Alexander said, according to historians.

"And, of course, they all started fighting about who the strongest was," said Philip Freeman, a professor of classics at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, and author of the book, "Alexander the Great" (Simon & Schuster, 2011). "Pretty much right away his generals started fighting over who got his empire, and they divided it up."

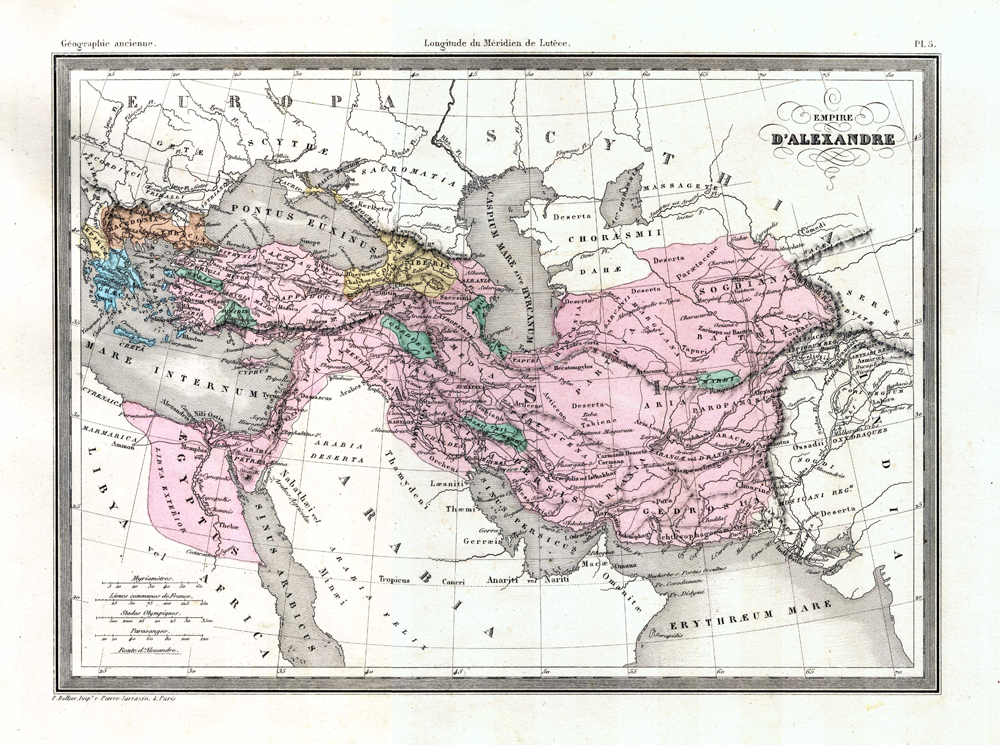

Alexander's empire stretched from Greece to the Indus River in present-day Pakistan, an impressive territory of about 2 million square miles (5.2 million square kilometers). The Roman Empire exceeded Alexander's in size, but the king built his faster, in just 13 years, before he died at age 32.

With his passing, Alexander the Great left an unborn son and a crowd of ambitious generals. His generals eagerly filled the power vacuum, and his rivals killed his son before the boy's 12th birthday. [10 Reasons Alexander the Great Was, Well … Great!]

At the Partition of Babylon in 323 B.C., rulers split the empire into sections, with Greece, Macedonia and southeastern Europe making up one portion, Asia Minor (present-day Turkey) another and northern Africa a third. Western and central Asia went to other rulers.

Ptolemy, a Macedonian general who served with Alexander, created a separate empire in northern Africa and southern Syria. At first, Ptolemy ruled as an appointed leader, but in 305 B.C., he declared himself king. The Ptolemaic dynasty ruled for 275 years, from 305 B.C. to Cleopatra VII's passing in 30 B.C.

One empire, one emperor?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But what if Alexander had explicitly left his kingdom to one person? Could this person have further expanded his empire, or at least continued to keep it together despite its incredible size?

It's unlikely the empire would have expanded, historians say. Lacking Alexander's charisma and acumen, it's doubtful any single general could have carried on in Alexander's place, following his death at age 32.

"If one person had managed to gain immediate control of the empire, it probably would have fallen apart," Freeman told Live Science. "There was nobody there who had the skill, intelligence, charm and military talent to hold it together like Alexander."

However, it's possible that Alexander didn't mean to express uncertainty about his successor and rather meant to hand his kingdom to his general Perdiccas, said James Romm, a professor of classics at Bard College in New York and author of the book, "Ghost on the Throne: The Death of Alexander the Great and the War for Crown and Empire" (Knopf, 2011).

But within two or three years of Alexander's death, while trying to attack Ptolemy's kingdom in Egypt, Perdiccas was killed by his own officers.

"He didn't do a very good job, and he didn't last very long," Romm said. Perdiccas' death highlights the fact that Alexander's demise led to an inevitable struggle for control.

"There was no one to whom he [Alexander] could pass power to that would have been able to hold the empire together," Romm said. "In the absence of a royal heir, there really was no one."

Would world maps and major religions be different now?

But if one person had continued the empire, the history of the world would have changed, historians told Live Science. A magnetic leader with military brilliance could have invaded Sicily and Rome when Rome was heavily involved in fighting its rivals in the Samnite Wars, which spanned, though not continuously, from 343 B.C. to 290 B.C. A well-timed invasion would have given Alexander's successor an enormous advantage, and, if successful, could have prevented the Roman Empire from forming, said Kenneth Sacks, professor of history and classics at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

Such a giant Greek and Macedonian empire could have altered the religious history of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, Sacks said.

It's possible that some Jews would have become more Hellenized than they are today under such an empire, as Greek culture had already influenced some Jews at the time, Sacks said. For example, Hellenized Jews tended to follow fewer dietary rules and may have tried to hide their circumcisions in the Greek gymnasium, where athletes competed in the nude, he added.

In contrast, Muslims might have become less Hellenized than they are today, because they may have not been as exposed to it, Sacks noted. For instance, the Byzantine emperor, Justinian I, persecuted Greek philosophers when he closed the Platonic Academy in Athens in A.D. 529. In response, the philosophers began moving east, away from the empire. Eventually, after Islam arose, many of the philosophers moved to Baghdad and strongly influenced Islamic thinkers with Neoplatonism, Sacks said.

And Christianity, without the backdrop of the Roman Empire, might not have spread to the West, Sacks said, explaining how the Church used the empire's protected roads and harbor systems to spread the gospel. Moreover, "the Church precisely copied the organizational pattern of the Roman Empire, assuring it control and stability," Sacks said. [In Photos: A Journey Through Early Christian Rome]

The continuation of Alexander's empire also would have changed modern-day maps.

"If there's no Roman Empire, there's no Europe as we know it," Sacks said. "So who knows what happens to Europe. It's still not Christian in any sense, or if there is Christianity, it probably would not have spread to Europe. It would have probably been localized as one of these Christian sects in the Middle East, many of which died out."

Without Rome, Europe would not have Roman technology, such as the aqueducts that carried water from distant sources to populated areas, and the use of concrete in harbors, which helped lead to the Renaissance, Sacks added.

Yet, no such leader existed. "None of these field marshals seem to exhibit the same kind of great vision that Alexander exhibited," Sacks said. "Alexander had a vision of how to stabilize an empire, how to maintain an empire, and none of his successors really demonstrated that capacity."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.