How to Find a Submarine

This article was originally published on The Conversation. The publication contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Das Boot, The Hunt for Red October, The Bedford Incident, We Dive At Dawn: films based on submariners' experience reflect the tense and unusual nature of undersea warfare – where it is often not how well armed or armoured a boat is that counts, but how quiet.

Submarines generate sound from their machinery and crew, and sound waves from other submarines or surface ships are used to find them. But of course submarines don’t want to be found. With the Swedish Navy currently hunting what is believed to be a Russian mini-submarine in Swedish Baltic waters, how can unseen boats below the water be detected?

Echolocation

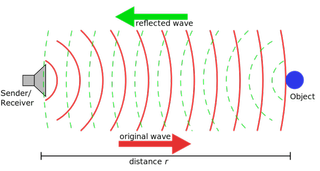

Sonar devices reveal objects below the surface by directing sound waves into the ocean and recording the sound waves reflected back. This is called active sonar – a form of echolocation much like that used by bats. Radar is also similar, but uses radio waves instead of sound.

Active sonar sources and receivers – essentially underwater loudspeakers and microphones – are usually distributed along a rope in an array and towed behind a ship. The length of the array is the equivalent to the aperture of a lens in optics: the longer the array the more sound it will receive, resulting in a higher definition and better quality sonar image.

Sonar works well if the submarine has a highly reflective steel surface and is surrounded by water at a constant temperature. But in the deep ocean the water temperature varies, which causes the water density to vary. This changing density creates an effect called the thermocline, which acts as a barrier, causing sound energy to bend away. A canny submarine captain can use the thermocline to good effect, effectively shielding the submarine from view.

Another ruse (one often seen in the films) is for a submarine to hide itself by coming to rest on the ocean floor, or near ocean cliffs and trenches. Here it’s difficult for the sonar to distinguish between echoes from rocks and from the submarine. If this wasn’t enough, modern submarines are shaped in such a way to minimise reflections, and are covered in coated tiles to absorb sound and minimise the boat’s profile even further.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Listening in

While sonar is well known, it’s rarely actually used to hunt submarines as it’s too easy to hide from the incoming sound waves. Instead modern anti-submarine warfare systems are actually extremely sensitive listening devices which rely on the submarine giving away its position by the sounds it makes. This is known as passive sonar.

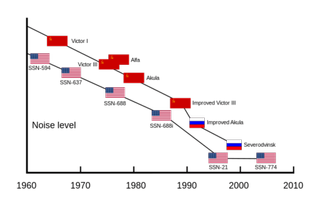

Surviving below the ocean without making any sound is pretty much impossible. Keeping the submariners quiet is the easy part. Much harder is keeping the submarine’s complex systems quiet – such as the machinery used to circulate air for the crew, or the boat’s engines.

So the first thing a submarine wishing to hide does is to shut down all unnecessary systems and, most importantly, come to a stop. This is important – a moving submarine disturbs the water, and the sound of the moving water leaves an imprint of sound waves that can be detected by the pursuer’s highly sensitive microphones.

Countermeasures

Given how hard it is to remain silent, submarine designers have spent a lot of time thinking of ways to minimise the sounds their systems make. For example naval nuclear power plants not only allow long missions at sea between refuelling but can also be cooled without using pumps, a source of noise. The final protection is the outer layer of tiles, which both reduce echoes from incoming sound waves and also reduce transmission of sound from within the submarine out into the ocean.

To find a submarine in the Baltic Sea is a challenge, as this area of relatively shallow waters is strewn with lots of small islands. To get the highest resolution images with active and passive sensors would require large arrays, often kilometres in length, to be towed behind quite large ships. But the complex ocean terrain makes doing so really tricky. In all probability Sweden will use relatively small arrays, and while these are still effective for detection, they are less able to discriminate between objects and pretty poor at accurate location.

All of which explains the current situation: the navy knows there is a submarine out there, but they just don’t know where. Ultimately there are just too many good places for a submarine to hide in this region. The hunt continues.

Bruce Drinkwater has received funding for research from the UK EPSRC and MoD as well as BAE Systems, Rolls-Royce Plc and ATLAS Electronik, all of whom are involved in aspects of submarine manufacture.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.