Experts: Great Barrier Reef's Biggest Threat is Coal

This article was originally published on The Conversation. The publication contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Reef historian Iain McCalman, in Sydney, and reef scientist Stephen Palumbi, in California, are monitoring reef degradation from opposite sides of the planet. They compared notes.

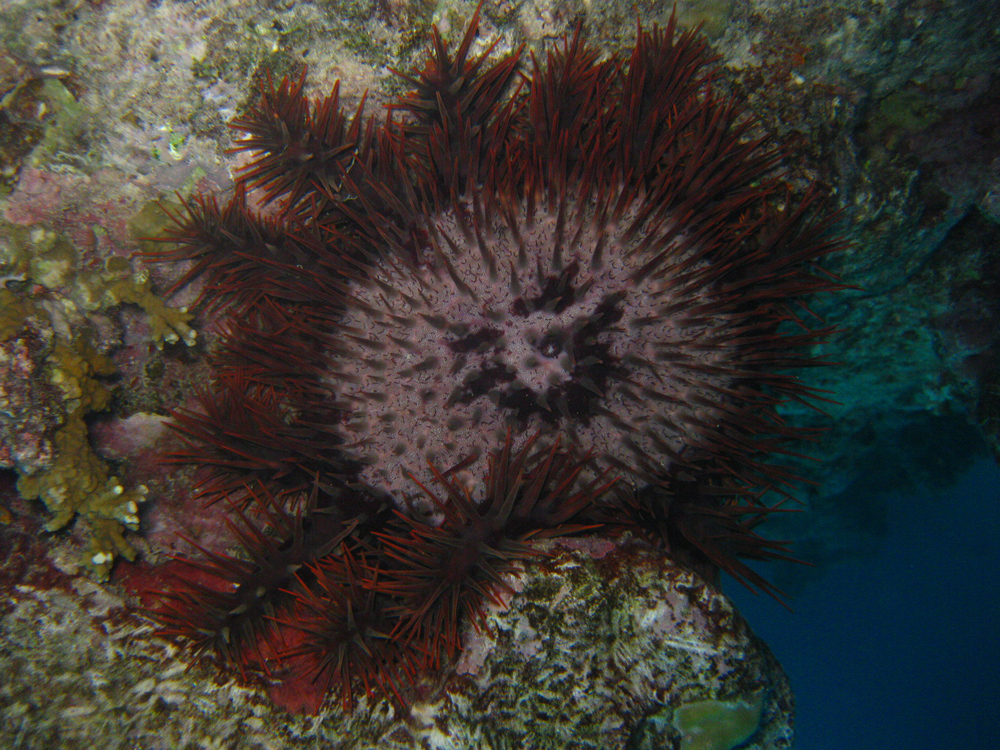

Iain McCalman: A recent report found that the Great Barrier Reef had lost 50% of its living coral. This was mainly from cyclones and the damages of Crown of Thorns starfish. Then there are the new threats of coral bleaching and acidification.

Are the problems you are finding in the US old ones that have mounted up and intensified? Or are they new challenges coming from human-stimulated climate change?

Steve Palumbi: All coral reefs in the world suffer from the same problems – they’re smothered by sediment, choked by weedy algae, blasted, dug up and stripped of most of their fish. Then there’s climate change making the oceans hot, sour and stormy.

Worst off are the reefs of the Caribbean, suffering from more than 500 years of incremental impact from western civilization, mostly in the form of poor stewardship. But even the far-flung reefs of the Pacific that the US manages have some combination of local stresses.

It seems to me that what the Great Barrier Reef has – that US reefs do not – is a central place in the hearts and minds of the public. Sure, most people in the US like corals and fish, but our reefs have not reached celebrity status. What kind of extra oomph does celebrity give the Great Barrier Reef? Has it been important in keeping it healthy?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Iain McCalman: The Great Barrier Reef’s popularity has helped control some things such as tourist pollution and the overfishing of parrot fish that graze on algae and keep corals clean.

Yet we haven’t been able to deter our governments from building massive new Reef ports and there are more and bigger coal ports on the way.

What worries me, too, is that waters warmed by greenhouse gases will cause big outbreaks of coral bleaching this coming summer, with stressed corals turning white as they expel the symbiotic algae that normally live within them. Another one degree or so will hurt corals that have been hit before: this time they may not recover.

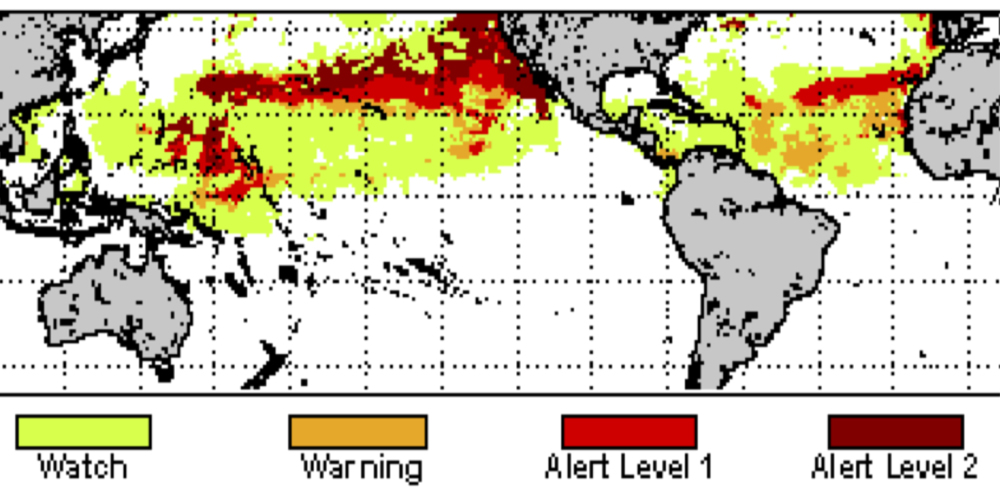

Steve Palumbi: I’m also worried about coral bleaching. This week along the US Pacific coast we have had record temperatures on land and in Monterey Bay – well, it is still very cold by Great Barrier Reef standards, about 60F (16C), but it is warm for us! And a look at the latest map of ocean temperatures shows a lot of red – these are places where the ocean is 1-2 degrees warmer than the usual annual maximum.

Iain McCalman: We are predicting something similar, especially because we seem to be entering an El Niño weather phase when the Pacific is generally warmer anyway, though Charlie Veron, one of our great coral scientists, says that every year is becoming an El Niño year in Australia as far as corals are concerned.

Steve Palumbi: Every year is a hot one … that seems to be what the world is seeing across the continents and the seas. Way back when people first stumbled on the fact that corals bleached when the temperature rose too much, they found something else: corals in warmer climates near the equator bleached at a higher temperature than corals living in cooler waters.

We have seen this on a small scale in American Samoa where we work, and have shown that individual coral colonies living in warm water acclimate to the heat by changing their physiology. And whole populations of corals adapt to heat by having the right genetic makeup across about 100 genes.

Can we use this discovery? Turns out we can in two ways. We can locate and protect these heat-resistant corals. And we can try transplanting them to see if they in fact retain their heat resistance. We expect them to lose a little ground. How much is the question.

I’d love to think this will give us a leg up in replanting future reefs. I am not sure yet, because reef restoration has been so difficult. Does the Great Barrier Reef have any successful restored, replanted reefs?

Iain McCalman: Not that I know of. Moreover, with a government skeptical about climate change, a good deal of the work of this kind on adaptation is being shelved. Five of the Directors of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority recently resigned in protest against the cutting of programs concerned with responding to climate change.

Five directors of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority recently took redundancy packages, among them its former climate change director Paul Marshall, who said budget cuts have left the agency without a dedicated climate program.

But I also wanted to ask you about acidification. As the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere rises, oceans absorb more and it turns into carbonic acid in seawater. How do you rate the mounting acidification of the oceans from absorption of CO2 as a threat to corals?

It seems to be the elephant in the room: its consequences go beyond endangering corals to threaten other marine species as well. Some scientists seem to think it will deliver the death blow to coral reefs, if other things don’t get them first. What’s your feeling?

Steve Palumbi: Acidification is not the elephant in the room yet, it’s the elephant on the bus … due to get here any time now. The best data suggest that acidification has huge effects, from slowing down coral growth to changing the behavior of coral reef fish so that they get eaten more easily. Those effects are not strong yet, but they are coming quickly as CO2 builds up in the atmosphere.

CO2 and acidification takes 50 years to reverse. Think of stopping distance – a speeding car takes a long time to stop. So too with acidification.

And that is what I worry about. Because by the time the effect of that CO2 is killing corals, it will be too late to do anything about it. It’s like cancer treatment. If you’re lucky, they find a tumor when it is small and maybe isn’t even bothering you. But that tiny tumor is a huge threat, and we jump on it to fix it.

But I want to circle back to something you brought up at the beginning. Australia is selling coal to China, I hear. What is going on?

Iain McCalman: This issue of coal lies at the heart of current threats to the Great Barrier Reef, and symbolizes an economic mindset that reef lovers everywhere are up against. Our government has decided that Australia’s economic future lies in selling cheap coal to China and India. To do this the Federal and Queensland state governments need to expand existing coal ports on the Reef because these provide the cheapest and quickest shipping routes to Asia.

Quite apart from discouraging investment in renewable energy by backing fossil fuels, this decision has fraught implications for the health of the Reef and its waters.

Because the reef is too shallow for massive container ships, the new coal ports all entail extensive dredging of the seafloor. Thankfully public agitation has temporarily deflected the government’s original plan to dump three million cubic meters of dredged silt from Abbot Point into the reef channel, where it would choke corals and swamp sea grasses. Even so, dredging will stir up immense amounts of sediment as well as coral-threatening bacteria.

The vastly increased tonnage of container ships churning up and down the tricky reef channel represents a further threat from reef accidents and oil spillages, both of which have occurred a number of times in the recent past. There are plans, too, for several new mega-sized coal mines to be opened nearby, requiring similar access to the Great Barrier coastline and lagoon.

To call this policy short-sighted is an understatement. It sacrifices one of the wonders of the world and a substantial economic asset for Australian tourism; and this at a time when even China is trying to wean itself from using polluting coal.

The Great Barrier Reef might be an icon for us in Australia, as you said, Steve, but we seem to have governments that are proud to be icon bashers.

Steve Palumbi: I am thinking about a wonderful passage in your book, about Captain Cook navigating the Great Barrier Reef’s intricate tributaries, straining his considerable navigational skills to delicately thread his small ship up coral-filled canals. Now blast a modern coal ship through there, and what would you expect to happen? Cook’s ship was threatened by the Great Barrier Reef. Now the tables have turned.

I can’t help also to think about one of the last major threats to the whole Great Barrier Reef - the crown of thorns starfish. It wasn’t too long ago that this voracious predator was wasting reefs all along Australia. The way you describe the dangers of mining and ports makes me want to call this new threat the Coal of Thorns.

The Coal of Thorns may prove to be an even bigger threat - because it is something the reef has never seen and it is on an industrial scale that could threaten even this biggest biological structure on Earth. And all to help China pollute their own air! What happens after you build all these ports, you export the coal and China turns to their vast supplies of natural gas? Dead reef and a dead exporting business.

When the coral-eating Crown of Thorns began devastating the Reef in the 1960s, people tried everything to stop it. Folks picked them up by the thousands and burned them. They poisoned them. They fought them up and down the length of Australia. They would have loved to have the problem solved by simply passing a law.

This threat from coal is a problem created specifically by people. And it could be solved by people in a way that was never available for the starfish scourge – a simple sign of a pen could do away with this major threat.

This article was amended on October 28, 2014, to clarify the circumstances of the departure of the five former directors of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

Iain McCalman receives funding from Australian Research Council.

Stephen Palumbi receives funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.