5 Science 'Facts' You Learned in School That Are Wrong

This article was originally published on The Conversation. The publication contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Let’s start with a quiz…

- How many senses do you have?

- Which of the following are magnetic: a tomato, you, paperclips?

- What are the primary colours of pigments and paints?

- What region of the tongue is responsible for sensing bitter tastes?

- What are the states of matter?

If you answered five; paperclips; red, yellow and blue; the back of the tongue; and gas, liquid and solid, then you would have got full marks in any school exam. But you would have been wrong.

The sixth sense and more

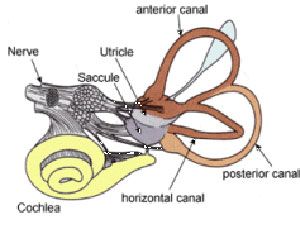

Taste, touch, sight, hearing and smell don’t even begin to cover the ways we sense the world. We sense movement via accelerometers, which are located in the vestibular system within our ears. The movement of fluid through tiny canals deep in our ears allow use to sense movement and give use our sense of balance. Make yourself dizzy and its this sense that you are confusing.

When we hold our breath we sense our blood becoming acidic as carbon dioxide dissolves in it forming carbonic acid. Not to mention senses for temperature, pain and time plus a myriad of others that allow us to respond to the need what is going on within us and the environment around.

Magnetic repulsion

It is not just paperclips that are magnetic. Both tomatoes and humans interact with magnetic fields, too.

Paperclip and other objects that contain iron, cobalt and nickle are ferromagnets, which means that they can be attracted to magnetic fields. While the water in you and the tomato – or more accurately the nuclei in the hydrogen in the water in you and the tomato – is repelled by magnetic fields. This interaction is called diamagnetism.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the forces involved are incredibly weak. So normally you don’t notice them. That is unless you have been in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine. In there, a massive magnet manipulates nuclei of various atoms inside you in such a way that results in detailed images of your inner workings.

Though you don’t need to go to a hospital to see diamagnetic interactions. Just use a couple of cherry tomatoes, a strong magnet, a wooden kebab stick and a pin:

And the types of magnetism don’t stop there, but that’s for another time.

You’re painting with the wrong colour

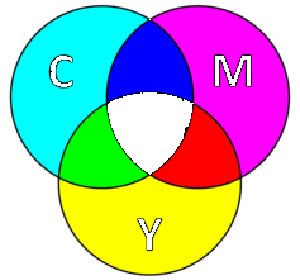

You were taught that primary colours are those that can’t be made by mixing other coloured pigments together, and that all other colours can by produced by blending these primary colours. Red and blue fail on both counts. You can make red by mixing yellow with magenta. While a blend of magenta with cyan yields blue. Meanwhile a massive range of hues are inaccessible if you start with just red, blue and yellow.

Colour theorists had this all worked out by the end of the 19th century but for some reason it hasn’t made it to school curriculums. The proof is in your colour printer cartridges. They come in cyan, yellow and magenta, which are the true primary colours.

A bitter taste in your mouth

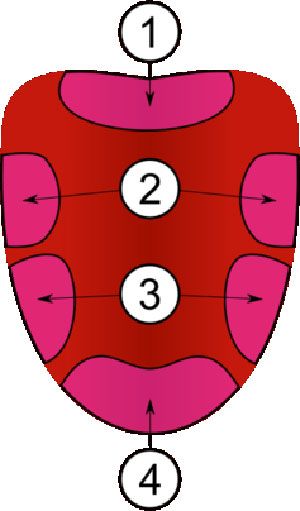

Remember those tongue maps that crop up in biology text books? They clearly show how the taste buds for bitter sit at the back of the tongue, with sweet, sour and sweet having their own discrete regions.

These tongue maps first appeared in 1942 after Edwin Boring of Harvard University misinterpreted a German study from 1901. Despite Boring’s mistake the maps soon started to appear in schools texts. Then in 1974 the topic was revisited and the whole idea was roundly discredited. Nevertheless over 40 years later tongue taste maps still persist in biology text books.

Look at the state of your screen

We all learned solids keep a constant shape because the molecules in them are ordered. These can melt to liquids which keep a constant volume and can be poured. Liquids evaporate to form gases that expand to take up the volume available to them. There we have the three states of matter, end of story.

Expect of course there is more. Liquid crystals have molecules that are ordered like a solid but are fluid like a liquid. These properties are vital for your cells, shampoo and of course liquid crystal (LCD) flat screen devices.

But why stop at four states. There is plasma, the state of matter for most things in the sun, or Bose-Einstein condensates, superfluids and dozens more.

Time to rewrite textbooks?

There are many more than the five “facts” that need to be fixed in school textbooks. I am not suggesting that we should start teaching 6-year-olds about matter that only appears in Nobel Prize-winning physics labs or filling the curriculum with detail on dozens of senses. But maybe we should stop telling kids fibs.

Perhaps a biology lesson should start with: “We have many senses, here are the five we are going to learn about.” Or a sentence dropped in here and there that mentions the existence of more than three states of matter. As for the tongue map, just rip that page out of the book.

Mark Lorch does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Mark Lorch is Professor of Science Communication at the University of Hull. He trained as a protein chemist, studying protein folding and function. His research now focuses on the chemistry of a broad range of biological systems including lipids, proteins and even plant spores. As well as his written outputs he gives regular talks to schools, the public and conferences, and he occasionally pops up on the radio and TV explaining science and technology to a public audience.