Tiny Human Stomachs Grown in Lab

They may be small, but new lab-grown miniature human stomachs could one day help researchers better understand how the stomach develops, as well as the diseases that can strike it.

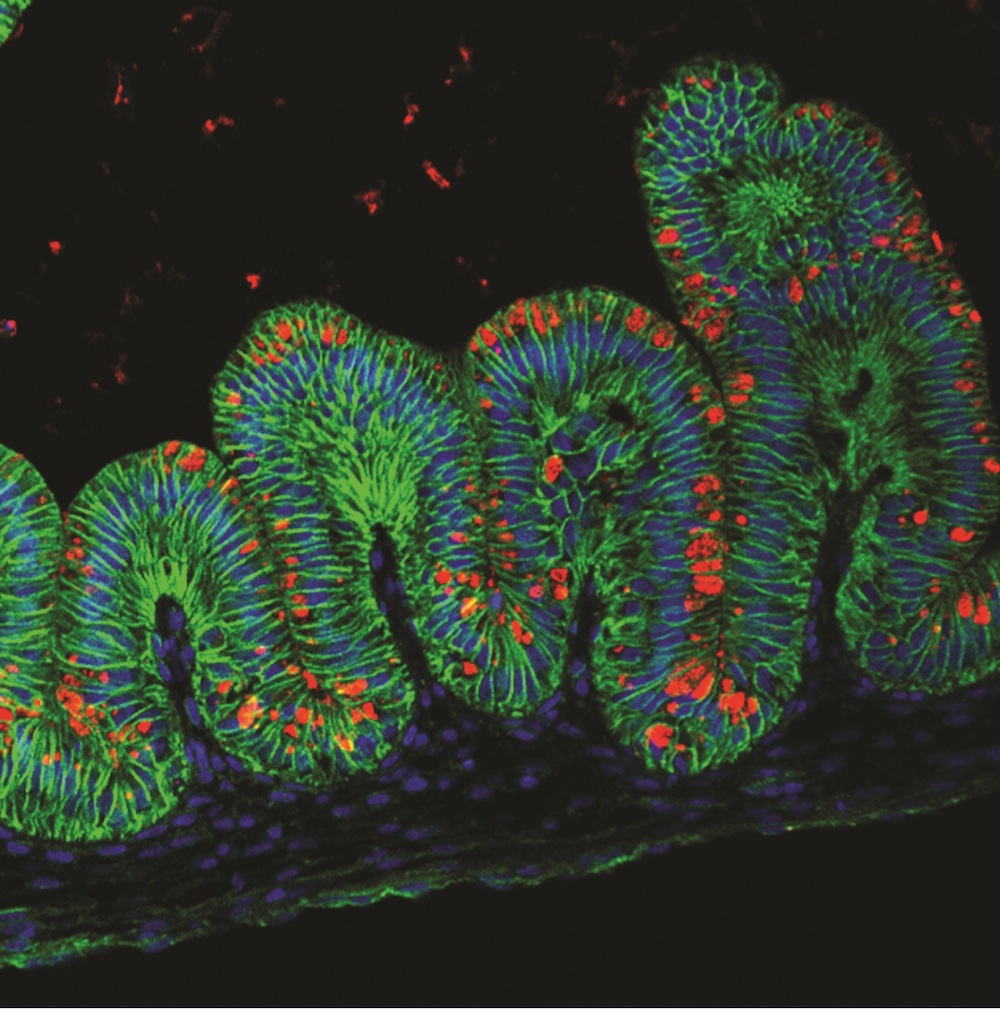

Using human stem cells and a series of chemical switches, researchers grew stomachs measuring 0.1 inches (3 millimeters) in diameter, in lab dishes, according to a report published today (Oct. 29) in the journal Nature.

"It was really remarkable to us how much it looked like a stomach," said researcher Jim Wells, a professor of developmental biology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. [See images of the tiny stomachs]

Growing a miniature stomach had its hurdles. There isn't much information on how the human stomach forms during embryonic development, so the researchers had to rely on basic research as well as trial and error, Wells said. Also, the ability to grow any three-dimensional organ in a lab is a fairly recent development. Other researchers have grown flat samples of gastric tissue, but few had successfully leapt into 3D territory, he said.

Technically, the small stomachs aren't organs, but organoids: miniature 3-dimensional structures of an organ. They took just about a month to cultivate.

"These gastric organoids are going to allow people to do experiments they were never able to do before," Wells said.

Stomach farm

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The experiment began with human pluripotent stem cells, which can become any cell in the human body if given the right chemical instructions. The researchers used two kinds of stem cells — one group was derived from a human embryo that was made about 15 years ago, and the other was derived from adult human skin cells, using a technique that won the Nobel Prize for medicine in 2012.

The researchers used chemicals to prompt the cells to create the definitive endoderm, which is a flat layer of cells that forms early during embryonic development. At this point, the cells could still become other cells, including those forming the liver, pancreas, lung or stomach.

Then, the researchers added two more proteins signals, to tell the cells to form a three-dimensional tubelike structure called the foregut.

"That's where we introduce our special mojo to go from 2D to 3D," Wells said. "We're triggering what would normally happen during embryonic development, when embryos start kind of flat, and then roll up into a three-dimensional embryo."

He described the organoids as "oval-shaped, hollow structures" with insides that have folds like those of a regular stomach. [11 Surprising Facts About the Digestive System]

Other scientists working on regenerative medicine called the development a big advance in gastric research.

"It's a beautiful study and very innovative," said Dr. Jason Mills, an associate professor of gastroenterology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, who was not involved in the research. "We're now able to take individual human patient's skin cells and turn them into little mini stomachs, or really one portion of the stomach."

The organoids are not quite complete stomachs. The stomach is divided into two parts, including one that makes the acid that digests food, and another, the gastric antrum, that makes proteins that control the production of acid and digestive enzymes. The organiods include only the gastric antrum.

"We didn't make the part of the stomach that actually makes the acid," but the researchers are now working on this, Wells said.

But the organoids can still help researchers learn about stomach disease and development, said Dr. Tracy Grikscheit, an assistant professor in pediatric surgery at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, who was not involved in the study.

"In this paper, they effectively reproduce most of the components of a portion of the stomach, the gastric antrum, allowing human disease to be modeled in a dish instead of a patient," Grikscheit told Live Science in an email. This may allow other scientists "to make progress toward future human therapies," she said.

Testing ulcers

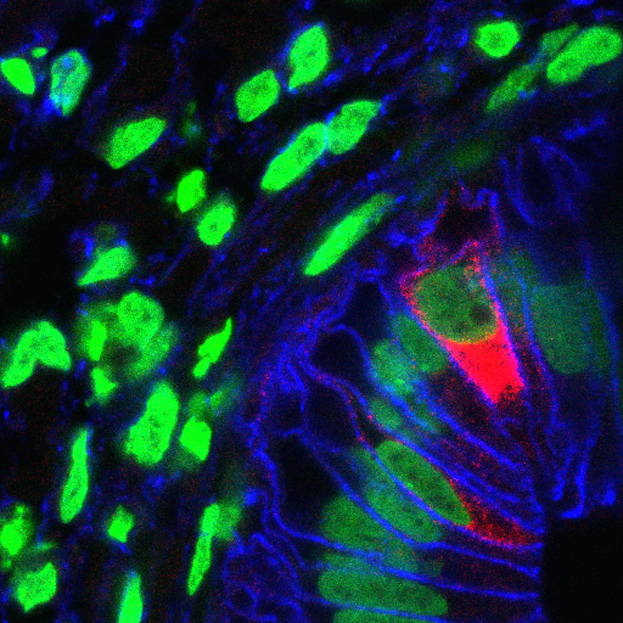

One application for the research will be using the stomachs to study the effects of a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori, which causes gastric disease in about 10 percent of people worldwide, and has been linked with stomach conditions from ulcers to gastric cancer.

Research in animals hasn't turned out to be a good way to study H. pylori's effects in people. The bacteria "doesn’t do the same bad things when you put it into a mouse stomach," Wells said.

Wells and his colleagues took the human stomach organoids to Yana Zavros, an assistant professor of molecular and cellular physiology at the University of Cincinnati, whose team injected them with H. pylori.

"The bacteria did pretty much what we expected it to do," Wells said, suggesting that the organoids are a good model for human disease.

The organoids may also one day serve as a source of patches of tissue that doctors could implant into patients with ulcer-damaged stomachs, he added.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.