How to Keep Race Horses Fracture Free

This article was originally published on The Conversation. The publication contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

In elite racehorses, biology is pushed to the limit – about four tons is placed on the joint surfaces in a galloping horse’s lower limb with every stride, and these repeated loads have the potential to cause injury to joints, tendons and bones.

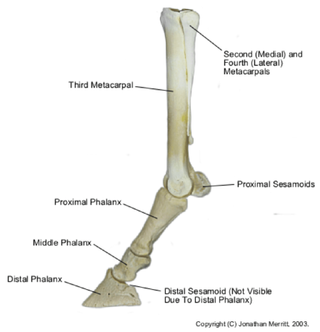

It’s not surprising then that injuries most commonly occur where the highest loads are generated: the carpal (knee) and fetlock (ankle) joints, and the flexor tendon and suspensory ligament.

So how do trainers ensure their horses stay injury-free?

As a horse runs faster, the loads it generates also increase, meaning that horses with a greater ability to run fast have an increased risk of injury. A common complaint from trainers is that it’s only the good ones that get injured!

Bone and tendon fatigue

Most injuries in racehorses are not due to an accidental bad step or collision with another horse. Rather, the most common cause of injury is what’s called “fatigue failure” of bone or tendon tissue such as:

- joint injury

- chip fractures

- catastrophic fractures

- tendon and suspensory ligament injuries.

These injuries occur spontaneously, often with little warning, and are caused by repeated high loading.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Despite the term “fatigue”, the horse does not get “tired”, but suffers a gradual deterioration of bone or tendon which ultimately ends in breakage, strain or rupture.

Fatigue failure is a difficult concept to grasp but can be likened to the fatigue that occurs in a wire that is repeatedly bent at the same point – eventually, and suddenly, it breaks.

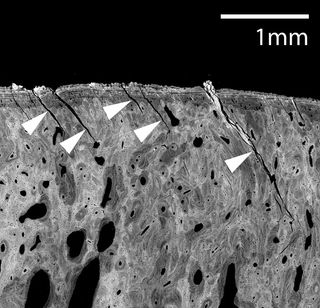

Adding to its insidious nature, the accumulated microdamage – injury at a microscopic level – is very difficult to detect and many horses show no signs of discomfort prior to significant injury. Yet when the bones or the tendons of horses are examined after injury there is often evidence of damage that has been present for some time.

Treating limb injuries

Bone has good potential for healing even in such large animals as horses. But due to their weight, and need to fully weight bear on all four limbs, only some fractures can be repaired.

Bone healing at joint surfaces is less satisfactory than typical bone fractures, and joint cartilage heals poorly so joint injuries often result in ongoing arthritis.

Poor healing is also a feature of tendons and ligaments so although many do appear to heal with prolonged rehabilitation, re-injury is common. Because the forms of effective treatments for limb injuries are limited, prevention is preferable.

Injury prevention

Prevention of limb injuries in horses has to involve a better understanding of how adaptation to the rigours of race training occurs, and the nature of repair of slowly accumulating damage.

Bone has great potential for adaptation, particularly in young growing horses. “Adaptation” refers to the new bone that’s rapidly laid down, both along the shafts of long bones and in the spaces underlying the joint surfaces, when young horses come into training.

Prior to this adaptation, though, fatigue failure can happen quickly. For example, cannon bone (third metacarpal) fractures generally happen around 8 weeks into a race preparation in young horses. In contrast, similar fractures in older experienced race horses with well-adapted bone tend to happen at around 20 weeks of training.

Bone’s intrinsic repair mechanism is not well understood. Throughout life, focal areas of bone are resorbed and replaced. This is a critical process for the prevention of injury because it allows fatigued bone to be replaced by new bone.

Our research has recently shown that in areas of bone stressed by repeated high loads – such as during training – this repair process slows, and those areas are prone to injury. In contrast, when horses rest from training, bone replacement rates are much higher.

In short, rest is best for replacing bone.

So what about tendons? Unfortunately, how tendons adapt to race training and repair accumulated damage is even less well understood than these processes in bone.

We currently don’t have enough knowledge to make specific recommendations on how far and how fast horses can go in training before risking injury, but we can make general recommendations.

The key to injury prevention is achieving a minimum number of miles of training at the necessary speed. There is a balance, though: adaptation will not occur if the horses do not train at speed, but if they train too much at high speed, then tissues will fatigue

Short sharp bursts of speed work once a horse is fit enough, two to three times a week, is usually appropriate. Duration of rest periods from race training are also difficult to ascertain, but we do know that more rest is better.

Horses will nearly always do what we ask of them. A large proportion of injuries to a racehorse’s limbs happen because trainers get the amount and intensity of training wrong.

We owe it to these incredible athletes to understand them better and that will only occur through greater research efforts and trainers basing their programs on the scientific evidence.

Chris Whitton receives funding from The Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation and Racing Victoria Limited.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.