Finding Spinosaurus: A Dinosaur Bigger Than T. Rex

A century ago, scientists unearthed fossils of a gigantic carnivorous dinosaur bigger than Tyrannosaurus rex in the Sahara desert, but until recently, paleontologists thought the fearsome beast was lost to history.

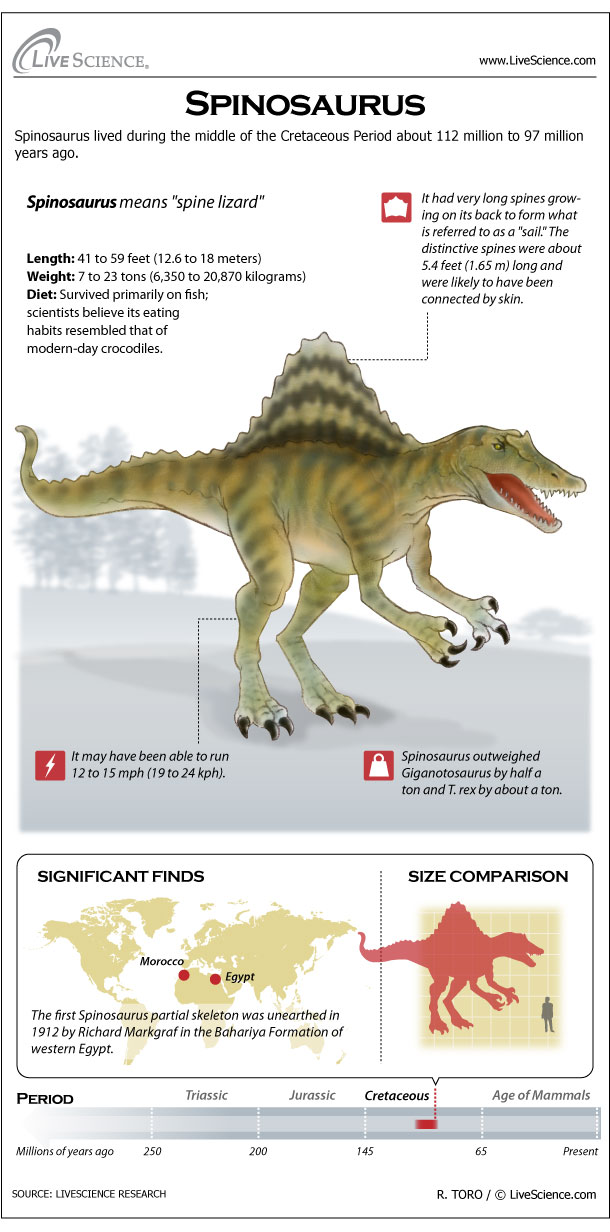

Known as Spinosaurus, the colossal predator sported a massive finlike sail on its back and a 3-foot-long (0.9 meters) jaw full of jagged teeth. Bigger than both T. rex and Gigantosaurus, it lived in the swamps and rivers of North Africa during the Cretaceous Period, about 112 million to 97 million years ago.

The only known specimens of Spinosaurus were destroyed during World War II, but a young paleontologist named Nizar Ibrahim has made it his life's work to track down traces of the massive beast. A new NOVA/National Geographic special follows Ibrahim on his journey to the dinosaur's final resting place. [In Images: Digging Up a Swimming Dinosaur Called Spinosaurus]

Bigger than T. rex

A German aristocrat named Ernst Freiherr Stromer von Reichenbach made several expeditions to the Egyptian Sahara between 1910 and 1914, and discovered dozens of new dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles and fish. Among Stromer's finds were two partial skeletons of a giant predatory dinosaur, which he named Spinosaurus aegyptiacus.

Stromer's skeletons were displayed in the Bavarian State Collection for Paleontology and Geology in Munich. During World War II, Stromer wanted to move the collection to a safer location, but he was an outspoken critic of the Nazi Party, and the museum director refused to move the skeletons. In 1944, Allied bombings destroyed the museum and with it, the only known fossils of Spinosaurus. Only a few old photographs and drawings remain, and Stromer himself has been largely forgotten.

But Ibrahim, now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago, and his colleagues launched an investigation to find more fossils of the elusive Spinosaurus.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dinosaurs have fascinated Ibrahim since he was five or six years old, he told Live Science. "I didn’t really see dinosaurs as big scary monsters or supernatural dragons, but as really interesting animals," he said. He learned about Spinosaurus from drawings in a children's book, but the illustrations were just guesses, since nobody knew exactly what the animal looked like.

By the time he was ready to begin a Ph.D. program, Ibrahim — who is half German and half Moroccan — decided to follow in Stromer's footsteps, and return to the "lost world" of dinosaurs in the Sahara.

Ibrahim wrote his own research proposal and obtained funding to travel to the border between Morocco and Algeria. There, he collected thousands of fossils, including the bone fragments and teeth of crocodiles, dinosaurs and flying reptiles. The ecosystem was totally dominated by predators, all living in the same place at the same time, Ibrahim said. "It was the most dangerous place in the history of our planet." [Photos: One of the World's Biggest Dinosaurs Discovered]

On a visit to Erfoud, Morocco, in 2008, Ibrahim came across a box of purplish stones with yellow streaks of sediment, containing what appeared to be a dinosaur hand bone and a flat blade bone with a creamy white interior. He bought the bones, even though he thought they were probably scientifically worthless.

The following year, Ibrahim visited the Natural History Museum in Milan, where some researchers showed him the partial skeleton of a giant dinosaur that they had obtained from a fossil dealer. Ibrahim immediately recognized it was a fossil of Spinosaurus. What's more, the bones were embedded in a purplish stone with yellow streaks, just like the one he had bought in Morocco. Ibrahim suspected the bones were from the same specimen, if only he could find where the rest was buried. But to do that, he would have to find the man who sold him the fossils.

"It was probably the craziest idea in the history of paleontology," Ibrahim said. He didn't know the man's name or address, all he knew was that the man had a beard. "It's not like finding a needle in a haystack, it's more like finding a needle in the desert," he said.

One day, Ibrahim was sitting in a cafe in Erfoud, ready to give up his hunt for the mystery fossil dealer. Just then, a bearded man walked by, and Ibrahim instantly recognized him as the man he had been looking for. The man took him to the original site where he had found the Spinosaurus bones, and there, the paleontologist dug up pieces of bone and teeth that matched those in the skeleton.

Ibrahim took the bones back to the University of Chicago, where he and his colleagues scanned them using a CT scanner, in order to create a digital reconstruction of Spinosaurus' skeleton.

But another mystery remained: Spinosaurus was a deadly predator, and it was found in an area with many other fearsome predators. How could the giant dinosaur coexist with so many competitors?

The answer seems to be that Spinosaurus lived in water for much of its life. It had long, slender jaws well suited for catching fish, short hind limbs that resemble those of the ancestors of whales, as well as flat claws and paddlelike feet. Spinosaurus' bones are also extremely dense, similar to other animals that spend a lot of time in water, Ibrahim said.

The purpose of the dinosaur's huge sail fin is still a mystery, but it may have functioned as a display structure to fend off would-be competitors.

"It's really exciting to find this incredible dinosaur," Ibrahim said. "But what's also interesting is the bigger picture." If you're trying to understand how the history of life on Earth has unfolded over deep time, "the Sahara is probably the best place to experience that," he said.

A life-size skeleton model of Spinosaurus is on display at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C., until April 12, 2015. The NOVA/National Geographic special about the monstrous dinosaur, called "Bigger Than T. rex," premieres Wednesday (Nov 5) at 9 p.m. ET (8 p.m. CT) on PBS (check local listings).

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.