Biggest Venomous Snake Ever Revealed in New Fossils

Walking the grasslands of what is now Greece 4 million years ago was a dangerous proposition: Lurking among the vegetation was the largest venomous snake ever known to man.

Laophis crotaloides measured between 10 and 13 feet (3 and 4 meters) long and weighed a whopping 57 lbs. (26 kilograms). Today's longest venomous snakes, king cobras (Ophiophagus hannah), can grow to be about 18 feet (5.5 m) long. But at typical weights between 15 and 20 lbs. (6.8 to 9 kg), king cobras are scrawny compared to Laophis.

What makes Laophis even stranger was that it achieved this bulk not in the tropics, where most large reptiles live today, but in seasonal grasslands where winters were cool.

"We've got something that, for its latitudinal placement and the climate reconstruction, it's massively out of proportion," said study researcher Benjamin Kear, a paleobiologist at Uppsala University in Sweden. [See Amazing Photos of Giant Snakes Around the World]

Lost fossils

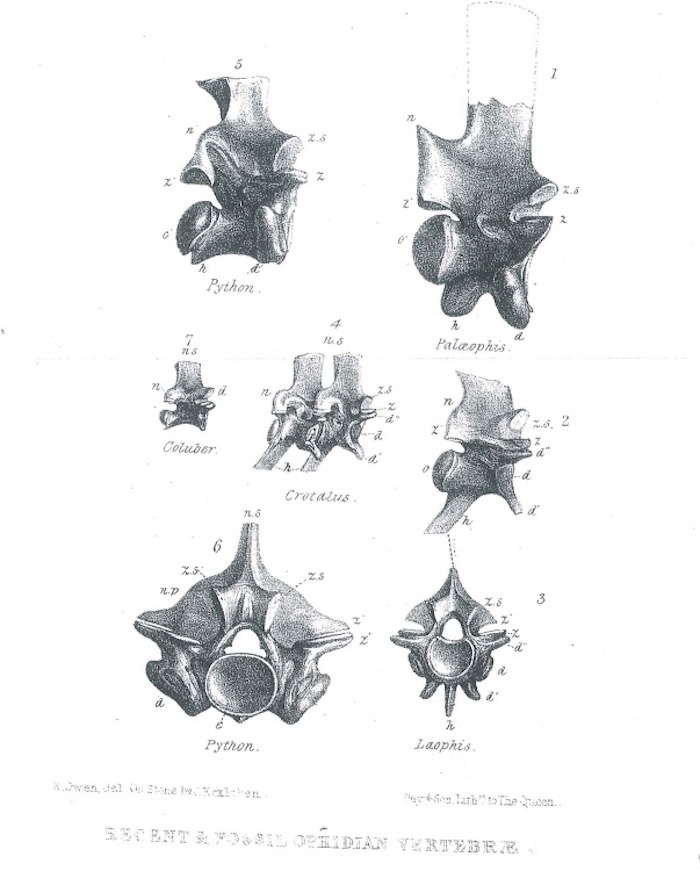

The tale of the enormous viper begins in 1857, when paleontologist Sir Richard Owen — the person who coined the word "dinosaur" — described 13 fossilized snake vertebrae found near Thessaloniki, Greece. Owen named the specimen Laophis crotaloides and reported it as the largest viper evr in the Quarterly Journal of The Geological Society (Vipers are one family of venomous snake, known for their hollow, retractable fangs.)

But the original 13 vertebrae have been lost, and no one had ever found any additional fossils to back up Owen's claim, said study researcher Georgios Georgalis, a graduate student at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. That is, until recently.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Now, a single vertebra, barely an inch long, found near Thessaloniki, confirms the existence of Owen's enormous viper.

"This snake was indeed impressive," Georgalis wrote in an email to Live Science. "We clearly speak about a monster!"

Snake vertebrae follow predictable patterns in relation to overall body size, which made it easy to extrapolate the snake's huge size from a single bone, Kear told Live Science. The snake is probably the largest viper ever found, far surpassing the modern record-holder Lachesis muta from South America, which grows up to a maximum length of 12 feet (3.7 m) and weighs no more than 11 lbs. (5 kg) or so. And the newfound snake's bulky body makes it the heavyweight champion of all venomous snakes who ever lived, viper or not.

Other, nonvenomous snakes do beat any of these vipers at the size game, however. Titanoboa, a boa constrictor-like snake from 60 million years ago, measured about 45 feet (14 m) long.

Mysterious size

For Georgalis and Kear, however, the intrigue comes not from record-breaking size alone, but from the question of what such a monster was doing in temperate Europe at all. Around 4 million years ago, the climate was cooling, and modern grassland ecosystems were emerging, Kear said.

The region where Laophis was discovered was also home to enormous tortoises, some of which grew as big as cars, Kear said. Because the climate was so cool, it's a mystery how these ancient turtles and snakes kept their metabolisms revving enough to grow so huge.

"Perhaps you're looking at unique aspects of their biology in the past," Kear said. "How did they do it?"

Little is known about Laophis' looks or lifestyle, as snake skulls don't preserve well in the fossil record, Kear said. But the enormous viper slithered alongside large mammals such as deer and horses, Georgalis said. It probably subsisted on a diet of small mammals like rodents.

Georgalis presented the findings today (Nov. 6) at the 2014 meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Berlin.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.