Falling Geckos Use Tails to Land on Their Feet

Like cats, geckos always land on their feet.

If the lizards happen to fall from a wall or leaf they've been climbing, a quick snap of the tail ensures that they land feet-first, a new study finds.

Geckos are truly built for climbing: Their specialized feet have hairy toes that can attach to and peel away from a wall or other vertical surface in just a few thousandths of a second. This built-in climbing gear lets geckos run 15 body lengths up a vertical surface in just one second.

Researchers had thought this was all the equipment the geckos needed to keep their feet firmly on … the wall. But it turns out that's not the case.

"We were pretty sure that was the secret," said study team member Robert Full of the University of California, Berkeley. "We were wrong; it's not the only thing."

A gecko's long, prehensile tail becomes essential to staying wall-bound when its feet falter on a slippery surface, and also if its feet can't keep hold and it falls to the ground, the new study, detailed in the March 17 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows.

Kickstand tail

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To see how the gecko used its tail to stay on a wall, Full and his colleagues put flat-tailed house geckos (Cosymbotus platyurus) on three vertical surfaces with different degrees of slipperiness, and monitored their reactions with a high-speed camera. In nature, a running gecko must deal with rapid changes in supports and surface textures.

When the geckos ran up a high-traction vertical track made of perforated board, their tails were held up off of the surface. But when a slippery patch was inserted into the board, their forefeet slipped toward their bodies; this slip caused them to move their tail tip toward the wall, "like an emergency fifth leg," Full said.

When made to run up a track of intermediate traction, the geckos' feet slipped a little with each step, and so they kept their tails in constant contact with the surface.

"Their tail taps the wall and keeps their head from tipping backward," Full told LiveScience.

When the geckos' feet slipped too much for the tail response to keep them against the wall, they kept themselves from toppling backwards by pressing the last two-thirds of their tail to the wall, like a bicycle's kickstand.

Falling geckos

Full and his colleagues noticed that when geckos fell or jumped off a wall, they always landed stomach-side down regardless of whether they began falling upside-down.

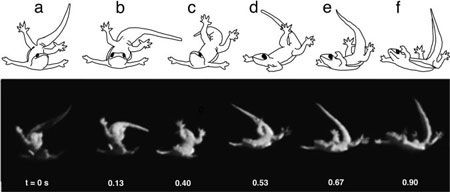

To find out how the lizards righted themselves mid-fall, the researchers conducted another experiment by placing the the geckos upside-down on a light, loosely-mounted platform that mimicked the underside of a leaf. When they lost their foothold and fell, the geckos pitched their tail so that it was at a right angle with their body. They then rotated the tail to make their body rotate. As soon as they were right-side up, they stopped rotating.

On average, it only took the geckos about 100 milliseconds to right themselves so that they would land on their feet.

Cats use a different mechanism to land on their feet after a fall. Because their tails don't have the heft a gecko's does (in comparison to the rest of the body), cats can't use them to right themselves. Instead they twist their bodies around mid-air.

Full and his colleagues have collaborated on their research with engineers who are trying to build a robot that mimics the geckos' climbing capabilities. It was the robotic research that first suggested that the geckos must use their tails for balance, as a tail had to be installed on the robot to keep it from pitching backward, Full said.

- Video: Geckos' Talented Tails

- Snakes, Frogs and Lizards: The Best of Your Images

- Amazing Animal Abilities

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.