Woman's Backward 'Mirror Writing' Had Unusual Cause

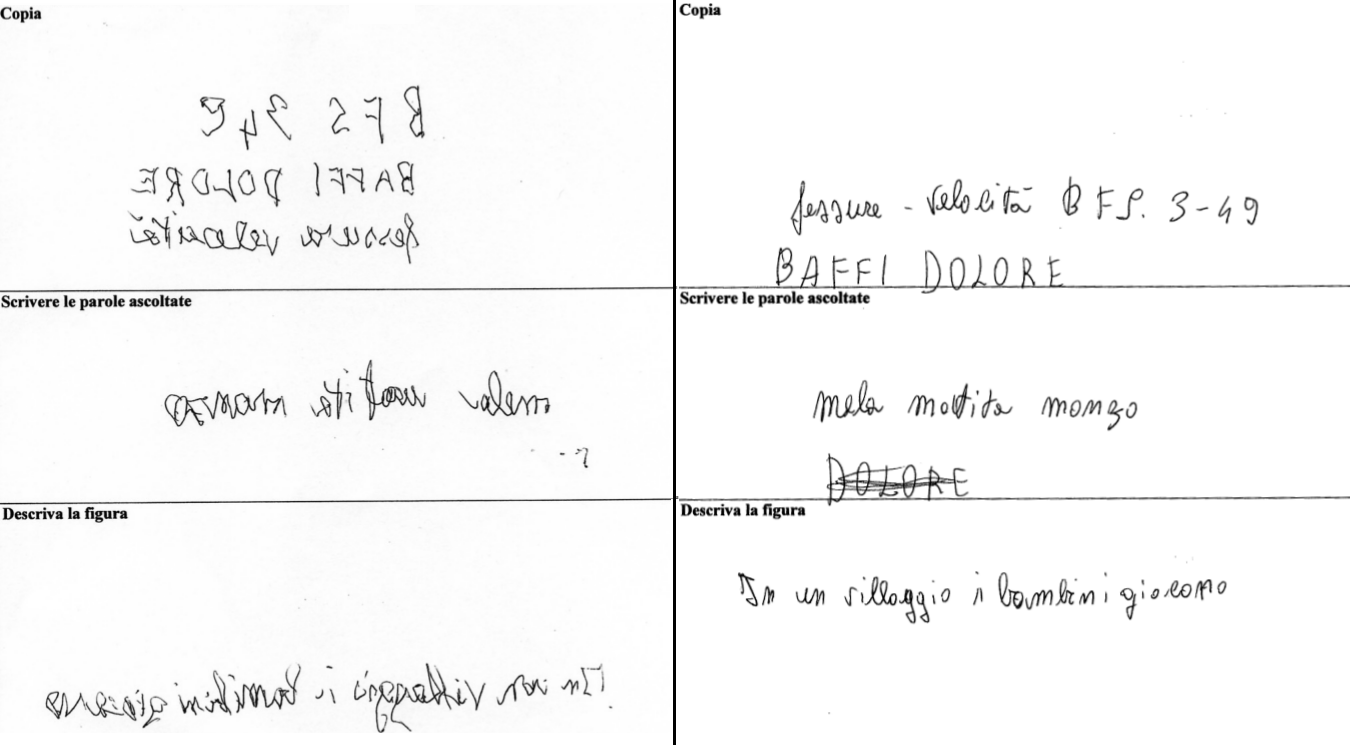

Writing letters backward and in reverse order, sometimes called mirror writing, may be a sign of a deteriorating brain, but in one woman's case, researchers found that the unusual condition was actually caused by anxiety.

Researchers in Scotland discovered the woman's condition accidentally while investigating mirror writing in people with mild cognitive impairment, a condition that may herald dementia.

Mirror writing is sometimes practiced as an artistic style; Leonardo da Vinci's personal notes are well-known examples. But doctors sometimes see people mirror write after a stroke that leaves them only able to use their nondominant hand for writing, said Sergio Della Sala, a professor of neuroscience at the University of Edinburgh.

The reasons for this "involuntary" mirror writing are not well understood, but scientists have suggested two main explanations. One possibility is that the phenomenon is a problem with movement, arising when the brain sends the wrong commands to the writing hand. Or, it may be a problem with perception, in which the brain becomes confused about how the letters should look, the second explanation posits.

Studying the neurological basis of mirror writing may offer researchers a window into how people learn handwriting, and how those skills deteriorate following brain injury, Della Sala said. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

The anxious mirror writer

After seeing anecdotal reports that people with cognitive impairment (and not full-blown dementia or brain damage) may engage in mirror writing, Della Sala and his colleagues decided to see if there was a relationship between mirror writing and the condition. They looked at 24 people with mild cognitive impairment, to see whether they showed any mirror writing.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found that only one person in the study showed "florid mirror writing" when writing with her left hand, suggesting that the phenomenon is actually not common among people with the condition.

But the researchers discovered something else. The participant who mirror wrote turned out to actually not even have mild cognitive impairment. Instead, psychological tests showed the 59-year-old Italian woman was actually suffering from anxiety. [16 Oddest Medical Case Reports]

"At the time of our first assessment, she had serious health-related family problems, causing considerable concern," Della Sala said. The anxiety had caused the woman to experience memory and mood problems, and she was incorrectly diagnosed with cognitive impairment.

"Some of the symptoms of depression and anxiety resemble those experienced by people in the early stages of dementia," Della Sala told Live Science.

The woman's mirror writing resolved when her anxiety receded a few months later, said the researchers, who published their study Oct. 17 in the journal Neurocase.

Curious clues

The case provides some clues about how mirror writing develops. Tests ruled out the idea that the woman's perception of the letters was off, Della Sala said. "Her ability to visually imagine words in their correct orientation was preserved," he said.

The woman's case also shows that mirror writing can be triggered by anxiety in an otherwise healthy person.

In fact, not all cases of mirror writing are problematic. For example, many children write backward when they are learning to write, and that's just a normal stage of development, Della Sala said.

"Several myths surrounding mirror writing in children should be dispelled," he said. "In particular, mirror writing is not associated with slower mental development."

Della Sala's own interest in studying mirror writing originated from a serendipitous observation, as is often the case in science, he said. "One of my daughters started to mirror write when she was 3," he said, "and I became determined to understand why."

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.