11 odd facts about magic mushrooms

Magic mushrooms contain a hallucinogenic with many strange properties, but did you know these true facts?

- Mushrooms hyperconnect to the brain

- They can slow brain activity

- Magic mushrooms go way back

- Magic mushrooms explain Santa…maybe

- Shrooms may change people for good

- Mushrooms kill fear

- They make their own wind

- There are many mushrooms

- Researchers are experimenting with shrooms

- Terence McKenna made shrooms mainstream

- Animals Feel the Effects

- Additional Resources

- Bibliography

At first glance, magic mushrooms, or Psilocybe cubensis don't look particularly magical. In fact, the scientific name of this little brown-and-white mushroom roughly translates to "bald head," befitting the fungus's rather mild-mannered appearance, according to TruffleMagic. But those who have ingested a dose of P. cubensis say it changes the user's world and it is now being seen as having positive effects during treatment for depression.

The mushroom is one of more than 150 species that contain compounds called psilocybin and psilocin, according to Science Direct, which are psychoactive and cause hallucinations, euphoria and other trippy symptoms. These "magic mushrooms" have long been used in Central American religious ceremonies, such as those of the Maya, according to Science Direct. They are now part of the black market in drugs in the United States and many other countries, where they are considered a controlled substance and illegal.

How does a modest little mushroom upend the brain so thoroughly? Read on for some of the strange secrets of 'shrooms.

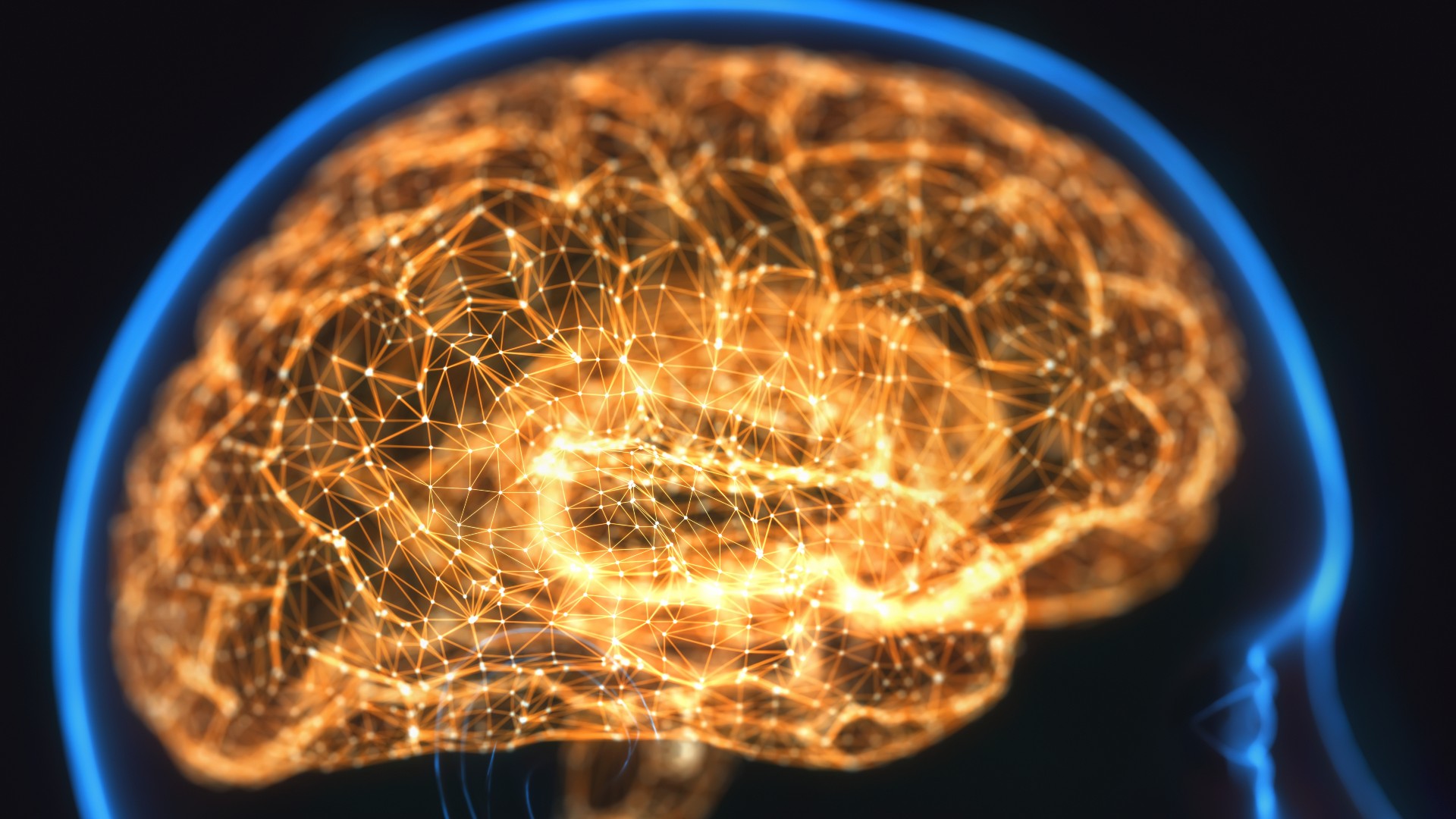

Mushrooms hyperconnect to the brain

The compounds in psilocybin mushrooms may give users a "mind-melting" feeling, but in fact, the drug does just the opposite — psilocybin actually boosts the brain's connectivity, according to an October 2014 study. Researchers at King's College London asked 15 volunteers to undergo brain scanning by a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine. They did so once after ingesting a dose of magic mushrooms, and once after taking a placebo. The resulting brain connectivity maps showed that, while under the influence of the drug, the brain synchronizes activity among areas that would not normally be connected. This alteration in activity could explain the dreamy state that 'shroom users report experiencing after taking the drug, the researchers said. In 2021, new research by Scientists in Denmark found that the drug might have rapid and lasting antidepressant effects, according to PsyPost.

They can slow brain activity

'Shrooms act in other strange ways upon the brain. Psilocybin works by binding to receptors for the neurotransmitter serotonin, according to a 2019 article in Nature. Although it's not clear exactly how this binding affects the brain, studies have found that the drug has other brain-communication-related effects in addition to increased synchronicity.

In one study, brain imaging of volunteers who took psilocybin revealed decreased activity in information-transfer areas such as the thalamus, a structure deep in the middle of the brain. Slowing down the activity in areas such as the thalamus may allow information to travel more freely throughout the brain, because that region is a gatekeeper that usually limits connections, according to the researchers from Imperial College London. Later research showed that Shrooms may help 'reset' the brains of depressed patients, according to Imperial College London.

Magic mushrooms go way back

Central Americans were using psilocybin mushrooms before Europeans landed on the New World's shores, according to Science Direct; the fantastical fungi grow well in subtropical and tropical environments. But how far back were humans tripping on magic mushrooms?

It's not an easy question to answer, but a 1992 paper in the short-lived journal, "Integration: Journal of Mind-Moving Plants and Culture," argued that rock art in the Sahara dating back 9,000 years depicts hallucinogenic mushrooms. The art in question shows masked figures holding mushroom-like objects. Other drawings show mushrooms positioned behind anthropomorphic figures — possibly a nod to the fact that mushrooms grow in dung. The mushroom figures have also been interpreted as flowers, arrows or other plant matter, however, so it remains an open question whether the people who lived in the ancient Sahara used 'shrooms.

Magic mushrooms explain Santa…maybe

On the subject of myth, settle in for a less-than-innocent tale of Christmas cheer. According to Sierra College anthropologist John Rush, magic mushrooms explain why kids wait for a flying elf to bring them presents on Dec. 25.

Rush said that Siberian shamans used to bring gifts of hallucinogenic mushrooms to households each winter. Reindeer were the "spirit animals" of these shaman, and ingesting mushrooms might just convince a hallucinating tribe member that those animals could fly, according to Psychedelic Spotlight. Plus Santa's red-and-white suit looks suspiciously like the colors of the mushroom species Amanita muscaria, which grows under evergreen trees. However, this species is toxic to people. Feeling like you've just taken a bad trip? Not to worry. Not all anthropologists are sold on the hallucinogen-Christmas connection. But still, as Carl Ruck, a classicist at Boston University, told Live Science in 2012: "At first glance, one thinks it's ridiculous, but it's not."

Shrooms may change people for good

Psychologists say that few things can truly alter someone's personality in adulthood, but magic mushrooms may be one of those things.

A 2011 study found that after one dose of psilocybin, people became more open to new experiences for at least 14 months, a shockingly stable change. People with open personalities are more creative and more appreciative of art, and they value novelty and emotion.

The reason for the change seems to be psilocybin's effects on emotions. People describe mushroom trips as extremely profound experiences, and report feelings of joy and connectedness to others and to the world around them. These transcendent experiences appear to linger. the experiments, the researchers took great pains to assure their participants did not experience "bad trips," as some people respond to psilocybin with panic, nausea and vomiting. Volunteers were kept safe in a room with peaceful music and calming surroundings. However a 2021 study provided results which seemed to contradict this and suggested instead that, despite popular belief, Psilocybin actually impairs productivity, according to Forbes.

In 2017, clinical trials showed that three doses of psilocybin mixed with cognitive behavioural therapy sessions helped patients quit smoking. In 2020, John Hopkins Medical Researchers showed that two doses rapidly and profoundly reduced depression.

Mushrooms kill fear

Another strange side effect of magic mushrooms: They destroy fear. A 2013 study in mice found that when dosed with psilocybin, the animals became less likely to freeze up when they heard a noise they had learned to associate with a painful electric shock. Mice that were not given the drug also gradually relaxed around the noise, but it took longer.

The mice were given a low dose of psilocybin, and the researchers said they hope this animal study will inspire more work on how mushrooms might be used to treat mental health problems in people. For example, small doses of psilocybin could be explored as a way to treat post-traumatic stress disorder, the researchers said.

In 2016, researchers at John Hopkins University showed a reduced depression and anxiety in patients with advanced cancer, also helping reduce fear, according to Scientific American.

They make their own wind

Mushrooms don't just exist to get people high, of course — they have their own lives, part of which is reproduction. Like other fungi, mushrooms reproduce via spores, which travel the breeze to find a new place to grow.

But mushrooms often live in sheltered areas on forested floors, where the wind doesn't blow. To solve the problem of spreading their spores, some 'shrooms (including the hallucinogenic Amanita muscaria) create their own wind. To do this, the fungi increase the rate that water evaporates off of their surfaces, placing water vapor in the air immediately around them. This water vapor, along with the cool air created by evaporation, works to lift spores. Together, these two forces can lift the spores up to 4 inches (10 centimeters) above the mushroom, according to a presentation at the 2013 meeting of the American Physical Society's Division of Fluid Dynamics.

There are many mushrooms

At least 180 species of mushroom contain the psychoactive ingredient psilocybin, according to Drug Science . According to a 2005 paper in the International Journal of Medical Mushrooms, Latin America and the Caribbean are home to more than 50 species, and Mexico alone has 53. There are 22 species of magic mushroom in North America, 16 in Europe, 19 in Australia and the Pacific island region, 15 in Asia, and a mere four in Africa.

Researchers are experimenting with shrooms

Researchers are now experimenting with psilocybin as a potential treatment for depression, anxiety and other mental disorders. This line of research was frozen for decades and is still difficult to pursue, given psilocybin's status as a Schedule I substance. This means the drug is classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as having no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.

In the past, though, psilocybin and other hallucinogenic drugs were at the center of a thriving research program. During the 1960s, for example, Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary and his colleagues ran a series of experiments with magic mushrooms called the Harvard Psilocybin Project. Among the most famous was the Marsh Chapel Experiment, in which volunteers were given either psilocybin or a placebo before a church service in the chapel. Those who got psilocybin were more likely to report a mystical spiritual experience. A 25-year follow-up in 1991 found that participants who got the psilocybin remembered feeling even more unity and sacredness than they said they'd felt six months after the fact. Many described the experience as life altering.

"It left me with a completely unquestioned certainty that there is an environment bigger than the one I'm conscious of," one told the researchers in 1991. "I have my own interpretation of what that is, but it went from a theoretical proposition to an experiential one. … Somehow, my life has been different knowing that there is something out there."

Terence McKenna made shrooms mainstream

Leary's psychedelic experiments are part of hippie lore, but the man who did the most to bring magic mushrooms to mainstream U.S. drug culture was a writer and ethnobotanist named Terence McKenna. He had been experimenting with psychedelics since his teen years, but it wasn't until a trip to the Amazon in 1971 that he discovered psilocybin mushrooms — fields of them, according to a 2000 profile in Wired magazine.

In 1976, McKenna and his brother published "Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide," a manual for cultivating psilocybin mushrooms at home. "What is described is only slightly more complicated than canning or making jelly," McKenna wrote in the foreword to the book.

Animals Feel the Effects

Psilocybin 'shrooms grow in the wild, so it's perhaps inevitable that nonhuman animals have sampled these trippy fungi. In 2010, the British tabloids, such as The Daily Mail, were abuzz with reports that three pygmy goats at an animal sanctuary run by 1960s TV actress Alexandra Bastedo had gotten into some wild magic mushrooms. The goats reportedly acted lethargic, vomited and staggered around, taking two days to fully recover.

Siberian reindeer also have a taste for magic mushrooms, according to a 2009 BBC nature documentary and a 2021 article by Psychedelic Spotlight. It's unclear whether the reindeer feel the effects, but Siberian mystics would sometimes drink the urine from deer that had ingested mushrooms in order to get a hallucinogenic experience for religious rituals.

Additional Resources

To learn more about mushrooms and the various forms of Fungi, try this article from LiveScience. For more news relating to psychedelics and the emerging industry, checkout Psychedelic Spotlight.

Bibliography

- "Psilocybe Cubensis Ultimate Guide", Truffle Magic

- Psilocybin, Science Direct

- F J Carod-Artel, "Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures" Neurologia, English Edition, 2015

- Eric W Dolan, "New research provides evidence that a single dose of psilocybin can boost brain connections" PsyPost, 2021

- "Psychedelic effects of psilocybin correlate with serotonin 2A receptor occupancy and plasma psilocin levels" Nature, January 2021

- Ryan O'Hare: "Magic mushrooms may 'reset' the brains of depressed patients", Imperial College London, 13th October 2017

- Giorgio Samorini, "THE OLDEST REPRESENTATIONS OF HALLUCINOGENIC MUSHROOMS IN THE WORLD (SAHARA DESERT, 9000 – 7000 B.P.)" Artepriestorica.com

- Derek Beres, "Santa Claus was a psychedelic mushroom", Psychedelic Spotlight, December 23 2020

- Rebecca Coffey, "Psilocybin Impairs Productive Creativity, At Least While Users Are ‘Stoned’ — Or So A New Study Suggests" Forbes, April 2021

- Richard Schiffman, "Psilocybin: A Journey Beyond the Fear of Death" Scientific American, December 1 2016

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.