How Virtual Reality Can Help Treat Sex Offenders

This article was originally published on The Conversation. The publication contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

The quality of virtual reality systems – immersive, computer-generated worlds – has advanced dramatically in recent years, as can be seen by the expansive editorial from journalists testing Oculus Rift headsets.

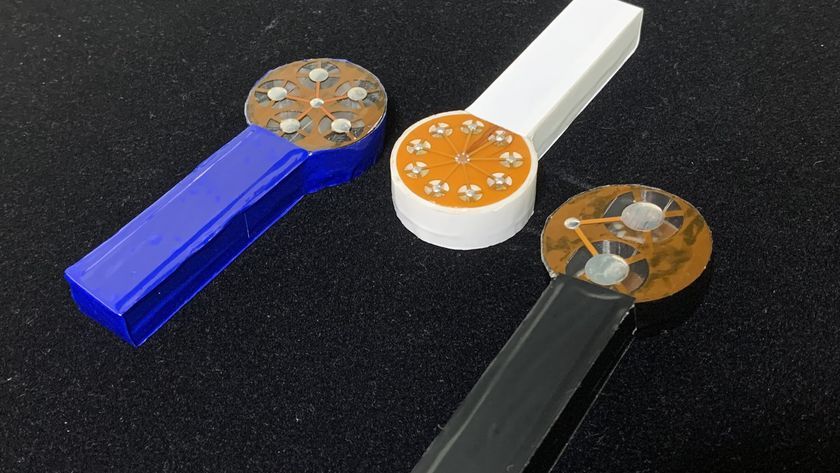

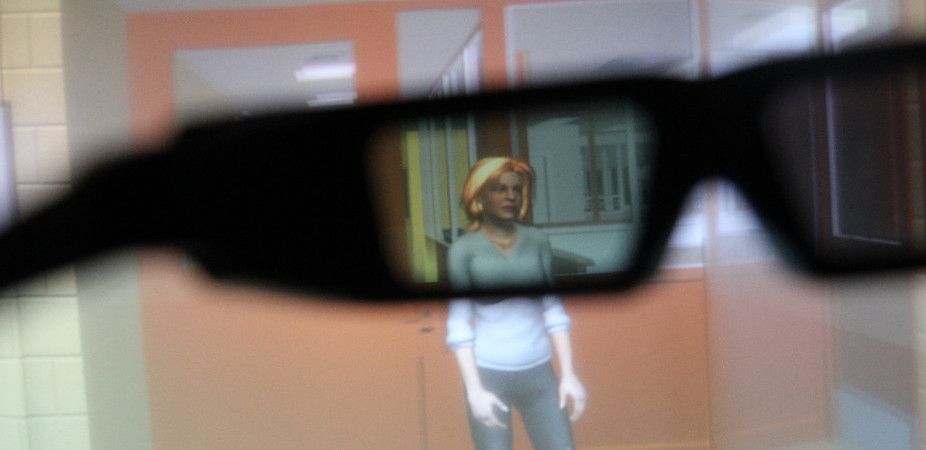

University of Montreal researcher Massil Benbouriche has used this realism to help understand the impulses of sex offenders in order to find better ways of treating them. Key to using virtual reality as therapy is the degree to which an individual identifies with the world. Benbouriche uses a virtual reality headset and various audio-visual stimuli within a “cave”, or a cube of screens, to provide an immersive experience to the participant.

Sufficiently real

Virtual reality treatments depend on immersion and presence. Immersion refers to the level of awareness of the real world during a virtual session – fully immersive systems, such as the one built in Montreal, carefully control the environment and inundate the participant with all the necessary stimuli, minimising the need to interact with real-world objects in a way that would break the illusion.

If this is achieved, physical presence is established – when the virtual world is sufficiently convincing to be perceived as a functional representation of the real world. Self-presence is the psychological connection the participant feels to the avatar representing them within the virtual world. The greater the level of self-presence, the more likely it is that users will identify with their virtual representation. The degree to which individuals can achieve presence determines the likelihood that the things learned in the virtual world will transfer to real life.

In the University of Montreal study, the researchers recorded the participants' physiological responses to what they were seeing and hearing. They used headsets that track eye movements and record how long participants spent gazing at images. They also measured participants sexual arousal through penile plethsymography (PPG), which measures the flow of blood to the penis.

Combining PPG and virtual reality to gauge the behaviour of sexual offenders in the past has been criticised because of the possibility that they game the system by simply not looking at the images. The eye-tracking capability of the headset overcomes this problem, recording not just which computer-generated images of adults or children the participants view, but over which areas of the body their gaze lingers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The differences in the data recorded when showing participants sexual and non-sexual, or nude and non-nude images, are compared. Studies have shown that the combination of these methods used in a virtual environment can effectively measure sexual interest.

Virtual reality, real life benefits

Virtual reality has been used in psychology as a treatment option for many behavioural disorders for more than a decade. Virtual reality therapy, together with psycho-therapeutic approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy, has been used to treat disorders among the general population, as well as criminal behaviour.

For example, researchers in the US have used virtual reality to treat anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and substance abuse. Recently, researchers at the University of Cincinnati used a virtual environment to deliver a 10-week cognitive behavioural-based therapy to improve social skills in a group of juvenile offenders. Using virtual environments has been shown to enhance rehabilitation by offering participants a safe, “no loss” environment during treatment.

Not a tool for all situations

There are potential obstacles to consider when using virtual environments to assess and treat sex offenders. The cost of the hardware and software development required to implement it is expensive. There’s also the cost of training clinicians how to use it.

The very realism offered by virtual therapies can also throw up barriers. Potential side effects for participants include what is known as cybersickness, with various symptoms from eye strain, headache and nausea, to sweating, disorientation, and vertigo.

There are also legal and ethical considerations. In some countries, even computer-generated images of nude individuals, especially those of children, can be illegal. In any case, sex offender research suggests there are many risk factors underlying whether an offender will re-offend. Depending purely on the physiological responses recorded through virtual reality simulations may ignore these risk factors. Ultimately this could lead to false assessments of sex offenders, either that they are rehabilitated when they are not or vice versa.

It’s a natural progression to use technology in the criminal justice system to help assess sex offenders and improve the treatments available; as technology has been used in other areas of criminal justice. It offers greater potential to customise treatments to each individual, uses the known beneficial effects of virtual reality-based cognitive behavioural therapy to boost offender rehabilitation, and can be used to gauge how effective a treatment has been.

With prison overcrowding and reducing budgets, this technology has the potential to improve lives and slow the revolving door in and out of the criminal justice system.

Bobbie Ticknor does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.