Armed with Phones, Amateurs Can Beat Pollution-Tracking Satellites

Citizen scientists already use their phones to report roadkill, light pollution and invasive plants, using free apps. But in 2013, Dutch researchers went a step further, transforming smartphones into scientific instruments.

With an inexpensive camera add-on and an app to direct volunteers, the scientists proved they could match, and, in some cases, even exceed the pollution-tracking skill of current satellites and ground-based instruments, according to a new study.

"The accuracy of the crowdsourced measurements is as good as any professional instrument," said project leader Frans Snik, an astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands. [In Photos: World's Most Polluted Places]

The snap-on optical device, called iSPEX, turns a smartphone camera into a spectropolarimeter, an instrument that measures how tiny, airborne pollution particles called aerosols scatter sunlight. The technology was modified from the SPEX instrument, a larger version intended for space missions that will orbit Earth and Mars.

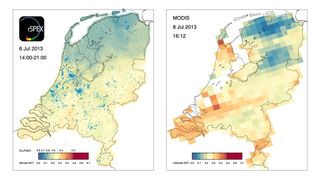

A single iSPEX shot is far from accurate. But 6,007 images, all snapped on the same day, can hit 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) accuracy or better, which is good enough to track down pollution sources, the researchers reported in a study published Oct. 27 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The iSPEX team was motivated to move from satellites to smartphones by a request from the Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Snik said. The institute had asked for ground-based instruments that could provide more information about the size and chemical composition of aerosols.

High levels of aerosols in lower layers of the atmosphere, where people live and breathe, can directly affect health, because the fine particles may damage the lungs and worsen conditions such as asthma. Aerosols higher up in the atmosphere may also play a role in climate change — different types of aerosols help to either cool or heat the planet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because there are still many uncertainties about the aerosols and their effects, researchers are keen to improve techniques for measuring the microscopic droplets and dust.

"The Netherlands is a hot spot for aerosol pollution within Europe," Snik told Live Science. "But these aerosol effects are so complicated that a lot of the processes are not very well-known."

Once they had a prototype camera filter in hand, Snik and his colleagues entered the Netherlands' annual Academic Year Prize competition in 2012. A $130,000 (100,000 euros) prize was offered for projects that communicated science to a wide audience.

The iSPEX widget beat out a traveling exhibition on the science of love and sex, and some polar explorers.

The prize money funded the app and factory run of 10,000 filters, also triggering a media blitz that garnered more than 8,000 volunteers.

By 2013, the only hurdle was waiting for a cloud-free day in the notoriously rainy Netherlands. Finally, on July 8, the weather was all clear.

More than 3,000 people snapped pictures with the iSPEX filter on the sunny July day. Aerosol levels were relatively high, thanks to smoke drifting across the Atlantic Ocean from forest fires in North America, Snik said. Two more tests, with fewer participants, were conducted later in July and in September.

The app directs people to stand with the sun at their backs and take photos from just above the horizon to the zenith. The greater the quantity of aerosols in the air, the less blue and polarized the sky will appear. The photos provide information on the total amount of aerosols, the particles' sizes and the types of particles. A color code provides immediate feedback, with the results ranging from blue for low aerosols to brown for high aerosols

The results were more accurate than the team had hoped, but Snik said he doesn't expect the phone filter to replace more expensive instruments. Instead, volunteers could fill in blind spots missed by current measurement networks, or help improve the accuracy of pollution tracking in urban areas, where the aerosol mix is complex, he said.

"It's really meant to add information to everything that's already out there," he said.

The iSPEX team is planning to expand the project into other countries with a grant that supports public activities in Europe during the 2015 International Year of Light.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.