Pucker Up: French Kissing Can Give You 80 Million New Bacteria

A 10-second kiss on the lips can transfer as many as 80 million bacteria into a person's mouth, a new study from the Netherlands finds.

The study also found that couples that kiss at least nine times a day have similar microbial communities in their mouths.

"During a kiss, you get exposed to many bacteria, but only a minor fraction of them are able to colonize the human body," said Remco Kort, a co-author of the study and a professor of microbial genomics at the University of Amsterdam. [Body Bugs: 5 Surprising Facts About Your Microbiome]

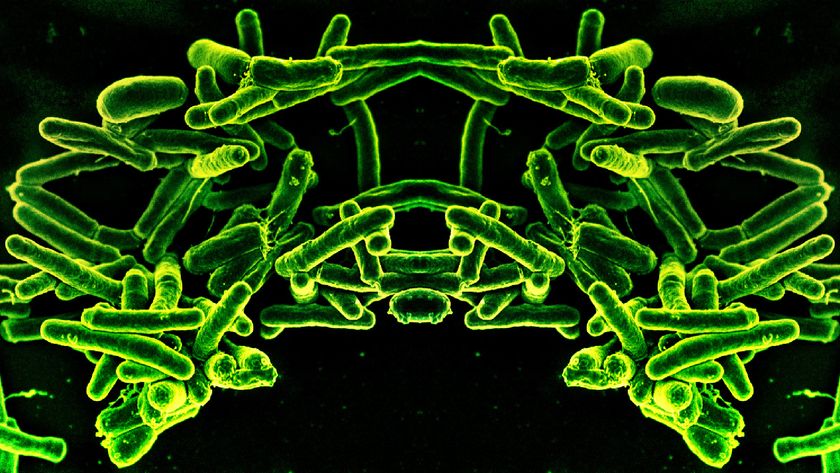

More than 100 trillion microorganisms live in and on the human body — the collection is called the microbiome. These bacteria help people digest food, synthesize nutrients and prevent disease, and the community is shaped by genetics, diet and age.

But kisses can also change your microbiome, according to the study, published today (Nov. 16) in the journal Microbiome.

The study included couples that the researchers found walking around at the Artis Royal Zoo in Amsterdam. The researchers asked 21 duos — including two gay couples — how often they kissed over the past year, and how long it had been since their last intimate kiss. They also swabbed the couples' mouths to take samples of the bacteria on each person's tongue and took spit samples to gauge their salivary bacteria before and after a kiss.

More than 700 types of bacteria live in the mouth. People who kiss frequently have similar oral microbiota, the researchers found.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study also found that the bacteria on the couples' tongues were more similar than those in their saliva.

The tongue, "is where the bacteria find a niche, and they colonize there over longer periods of time," Kort said.

In contrast, "The saliva is a very dynamic environment," Kort said. "In this, we could see the direct effect of a kiss, but it disappears over time."

Pat Schloss, an associate professor of microbiology at the University of Michigan, who was not involved with the study, said "what's cool is that they found that the more close in time they were to the last kiss, the [microbial] communities were more similar to each other, and that the more kisses you have per week, the more similar you are to each other," Schloss said.

But it's unclear what these shared microbiomes might mean for people's health, Schloss said. Researchers are studying how fecal transplants can influence the microbiome, but there is little research into the health effects of French kissing on significant others.

The Dutch researchers did one more test: One member of each couple drank a yogurt drink containing bacteria called Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria. Then, after the couple shared a 10-second, intimate kiss, researchers took a sample of the bacteria in the mouth of the partner who hadn't drank the yogurt.

They found that the partners' bacteria levels had increased threefold, which amounts to about 80 million new bacteria, the researchers said.

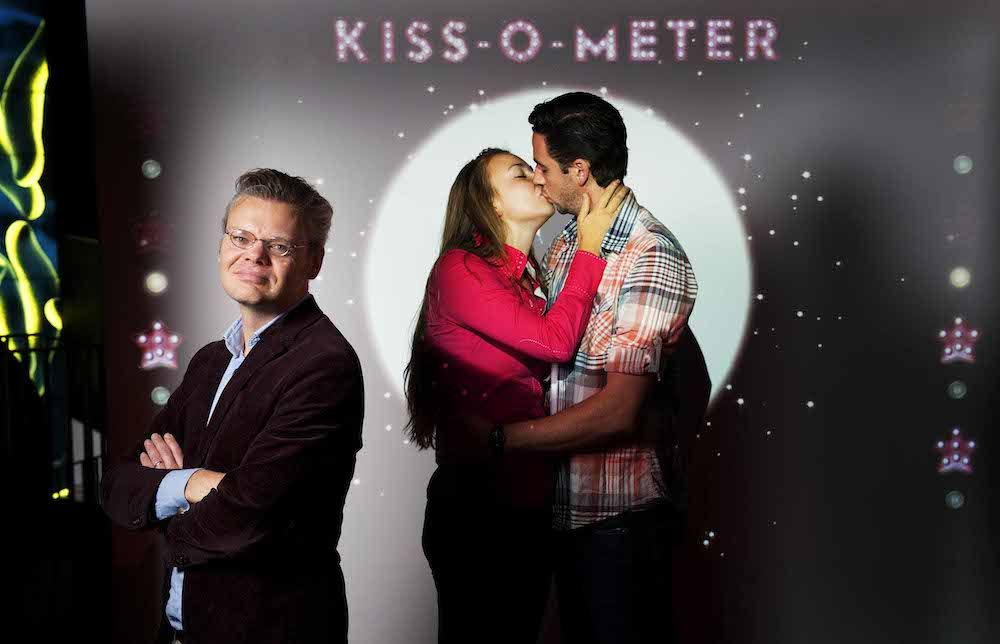

The results of the study are already being put to use at the kiss-o-meter, an interactive exhibit at Micropia, the world's first museum of microbes in Amsterdam. Couples can kiss at the museum, and a sensor will read the type of kiss and the number of bacteria likely transferred between the two people, said Kort, who is also an adviser for Micropia.

The study also revealed that 74 percent of men reported a higher frequency of kissing than their female partners did. Overall, men in the couples reported about 10 kisses per day, whereas the women reported about five kisses per day.

One gentleman reported receiving an average of 50 kisses a day, while his partner reported an average of only eight. The researchers excluded his data from the analysis on kiss frequency, they said.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.