Why Dried Whiskey Under Microscope Looks Like Art

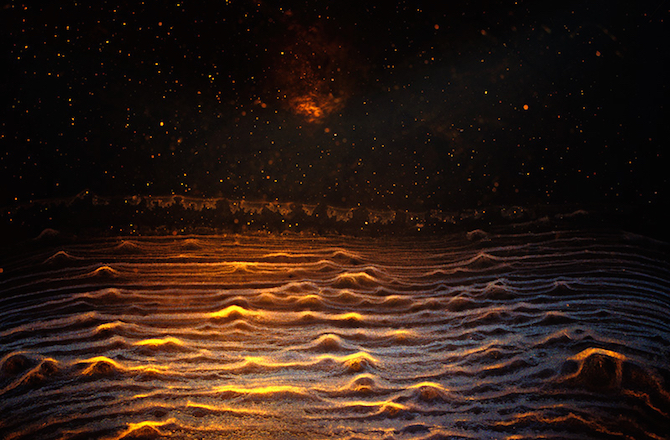

Dried whiskey at the bottom of a glass produces stunning images that closely resemble fine art paintings, shows new research that also helps explain how the patterns form.

The effect results from both the chemical composition of whiskey as well as fluid dynamics. The presentation “Painting Pictures with Whiskey,” explaining the phenomenon, took place today during the American Physical Society’s Division of Fluid Dynamics Meeting, held in San Francisco.

7 Ultimate Destinations for Booze Aficianados

Phoenix-based professional photographer and artist Ernie Button has been creating photos of the patterns formed after letting a drop or two of whiskey coat and dry in the bottom of a glass.

“It’s infinitely fascinating to me that a seemingly clear liquid leaves a pattern with such clarity and rhythm after the liquid is gone,” Button said in a press release.

Curiosity compelled him to reach out to Howard Stone and his Complex Fluids Group at Princeton University’s Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering for insight.

“My group focused on gaining a better understanding of the composition of whiskey, identifying the possible ‘suspended material,’ and doing controlled model experiments to understand possible shapes and forms of deposits during evaporation,” Stone explained.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To study the flow patterns and concentration in the solution, as well as the final dried deposits from suspended particles, a postdoctoral researcher in Stone’s lab, Hyoungsoo Kim Kim, and colleagues used video microscopy of drying droplets of actual whiskey and compared it to video microscopy of an alcohol-water solution representative of whiskey. Typical whiskies are 40 percent by volume ethanol (alcohol) and 60 percent by volume water.

Optical Illusions: Your Brain Is Way Ahead of You

They found that initially, the droplet of alcohol-water solution creates a complex mixing flow. Ethanol evaporates first, due to the lower vapor pressure compared to water. Once the ethanol vanishes, a radial pattern can be observed.

As the initial ethanol concentration increases, the mobility of the receding contact line is increased as well. At high ethanol concentrations, the contact line recedes and draws groups of particles along with it that are then deposited in ring-shaped patterns.

All demonstrate what is known as the Marangoni Effect, which is the mass transfer along an interface between two fluids (in this case, alcohol and water) due to surface tension.

“The alcohol-water solution shows circulation flow patterns (triggered by the Marangoni Effect), which occur during drying and influences patterns formed in evaporating whiskey solutions,” Kim noted. “Deposits in the actual whiskey come from a small amount of inherent raw materials present from the preparation process.”

Barrel aged whiskey, for example, might leave behind trace particles of oak or other woods.

Is Climate Change Ruining Wine Corks?

Stone even wondered if younger versus more aged versions of the same whiskey would create different patterns, but he and his colleagues could find no such differences. Perhaps that’s because the basic components are all still the same, even if the two whiskies develop different flavor properties.

The work by Stone’s group may have wider implications, because the ability to control the deposition of a thin film of particles is highly desirable for many industrial applications. The science behind all of this also helps to explain patterns left behind by other beverages, such as wine, tea (think reading tea leaves) and coffee.

To see more of Button’s photography, including what single malt Scotch looks like when dried and up close, visit his website.

Originally published on Discovery News.