Beyond the Vortex: A Winter Wonderland of Cause & Effect (Op-Ed)

Matt Kelsch is a hydrometeorologist with COMET, a division of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR). Kelsch contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

A fast-moving but potent nor'easter is bringing rain, snow and wind to the urban corridor from Virginia to Maine on Thanksgiving Eve, one of the busiest travel days of the year. The storm is taking advantage of the still-warm ocean and the cold air mass over the central United States, and there is travel-snarling heavy snow in, or just inland, from the major coastal cities.

But this is neither the first nor the most record-setting preview of winter that we saw in November 2014. During the middle of the month, impressive record-cold weather reached from the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains to the East Coast and contributed to an unusual early season snow cover of 50 percent for the contiguous United States.

Even snow-savvy Buffalo, N.Y., met its match when "lake effect" snow squalls formed as cold arctic air swept along the length of Lake Erie converting the relatively warm, moist lake air into narrow bands of intense snow. The result was locally paralyzing snowfall to depths up to 5 feet (1.5 meters) within a 24 hour period, and storm totals greater than 7 feet (2.1 meters), perhaps making it the most intense such storm associated with Lake Erie. This time-lapse shows the snow-laden clouds moving eastward from Lake Erie into the hard-hit southern suburbs of Buffalo.

Meanwhile, it recently rained in Barrow, Alaska, a place where the average daily temperature hovers around zero Fahrenheit in mid-November and the sun slipped below the horizon for two months beginning November 19th.

Why such extremes?

El Nino, the polar vortex, the jet stream, snow cover in Siberia, typhoon Nuri — all of these phenomena have been thrust into the gamut of explanations for the extremes observed from one end of North America to the other.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As one tries to make sense of those terms, remember that weather news makes for profitable entertainment, and exciting new weather terms are golden. But these weather and climate terms really do have meaning and represent great progress in meteorology's ability to put together pieces of the weather forecast puzzle, even if the terms are misused at times.

The jet stream and the polar vortex

So what do the terms mean? Let's start with the simple reminder that the jet stream forms in the upper atmosphere between the cold polar regions and the warm tropics. The jet stream encircles the Earth at somewhere between 4.5 miles to 7.5 miles (7.2 kilometers to 12 kilometers) above sea level, flowing rapidly from west to east, with the warm air on the equator side and the cold, denser air — the polar vortex — on the poleward side.

If the Earth's surface were featureless, the jet stream would likely follow a nearly perfect circle around the world, and the cold air would stay in polar regions. But the Earth's varied land forms and vast oceans, with their warm and cold currents, cause big differences in how the planet's surface warms. As a result, the jet stream departs from its west-to-east flow and zig zags in places, allowing tropical air to penetrate into polar regions while arctic air surges down into mid-and low-latitude areas.

In extreme cases, like mid-November 2014, record warmth penetrated the arctic region, enhanced in part by the powerful remnants of Pacific typhoon Nuri, which followed and strengthened a northward kink in the jet stream near the Bering Sea off Alaska.

That disruption to the west-east oriented jet stream resulted in a southward kink of that river of air ,which pushed record cold into middle latitude areas of the mainland United States. Following the cold wave, the "wavy" jet stream led to a quick warm-up in the central and eastern United States followed by another cold surge in time for Thanksgiving Eve while much of the West should see mild Thanksgiving weather.

The ghost of the winters yet to come?

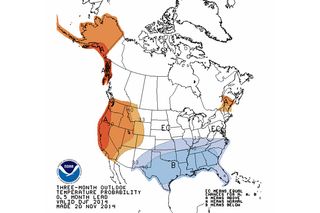

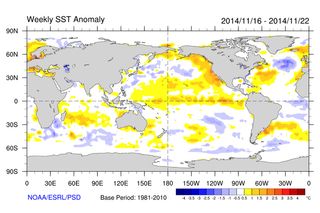

So many are wondering if this pattern is an indication of the winters to come. Some indications in the arctic suggest it may be, such as an above-average amount of early-season snow cover in Siberia, which may be correlated with cold winters in the central and eastern United States. But there is also growing evidence that a weak to moderate El Nino is emerging in the tropical Pacific, and El Nino winters are usually — but not always — associated with reduced risk of frequent arctic outbreaks (frequent multi-day spells of very cold air that originated in the frozen tundra of the arctic region) and potentially more rain for drought-stricken southern California.

The winter forecasts for 2014-2015 in the United States vary across the different projections from government agencies and private enterprise. The large snow cover in Siberia has prompted some to call for a winter with more cold-wave action than usual. Yet the increasing indications from El Nino have some, such as NOAA, calling for a lowered chance for frequent spells of arctic cold. The data that the different agencies analyze is pretty much the same, but the weight assigned to each of the many driving forces differs.

Regardless of the overall winter patterns, major precipitation events still unfold on a local scale in response to local weather features, terrain, land-water boundaries, etc. While part of metro Buffalo received more than 60 inches of snow as of November 19th, other parts of the metro area received only a few inches, practically picnic weather for Buffalonians!

As this winter season unfolds and brings forecast successes, as well as new learning opportunities, forecast techniques and the corresponding training will evolve to keep pace with the exciting revelations in weather and climate science.

For those interested in learning more, the UCAR COMET Program offers hundreds of hours of online training in natural sciences through the MetEd website with lessons in winter weather and climate science including more information on the jet stream, lake effect, orographic influences, banded snow and other topics.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.