Grisly Sale: Oliver Cromwell's Copper Corpse Plaque Up for Auction

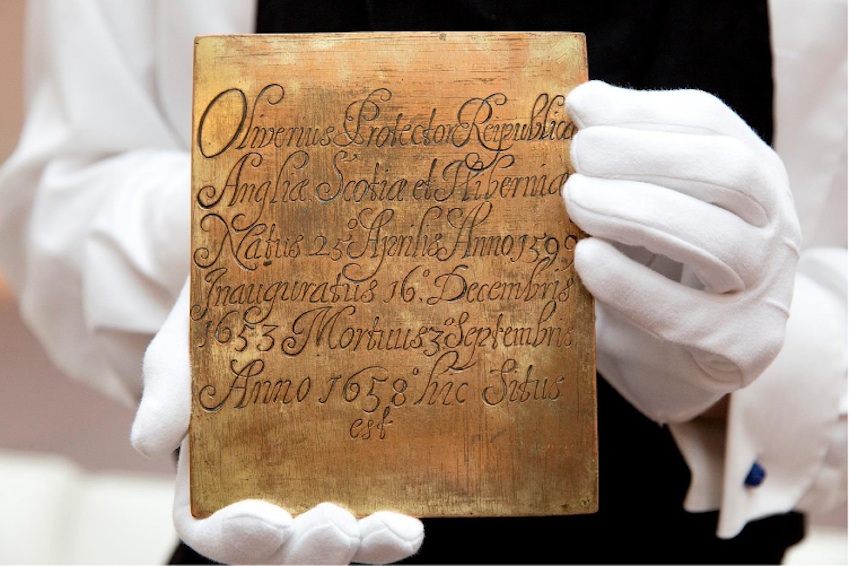

A gilt copper plate that once adorned the corpse of Oliver Cromwell is going up for auction.

The plaque sports a detailed engraving of the arms of the Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland and bears a grisly history: The plaque spent only two years in the grave of the Lord Protector before it, and Cromwell's corpse, were exhumed so that the corpse could be hanged, drawn and quartered — an act of revenge by Cromwell's once-defeated enemies.

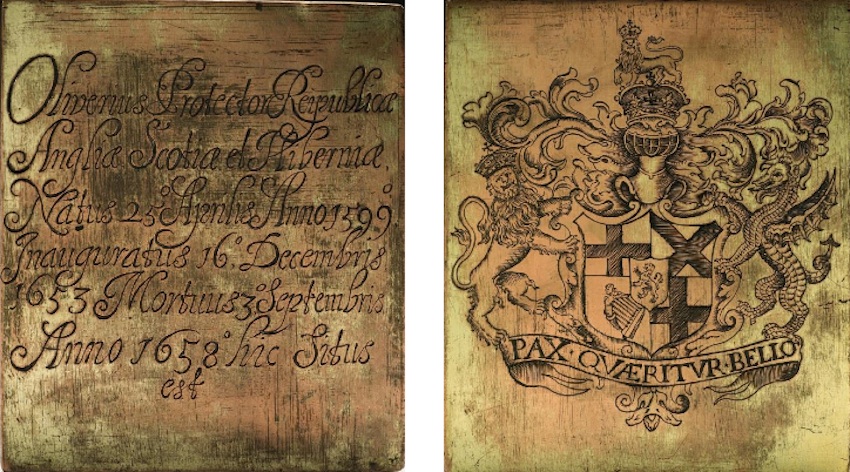

The copper plaque was pocketed by James Norfolke, the sergeant of the House of Commons, during the exhumation, according to Sotheby's, which will put the plaque on the auction block in London on Dec. 9. It measures 6.5 inches high (16.5 centimeters) and 5.5 inches wide (14 cm). One side bears the elaborate coat of arms, flanked by a lion and a dragon and bearing the motto "Pax Quaeritur Bello" ("Peace is sought by war"). [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

The other side of the plaque bears a Latin inscription recording Cromwell's title and the dates of his birth, inauguration and death.

Cromwell's rise

The dates tell only a fraction of Cromwell's story, which remains controversial to this day. Cromwell was born into a wealthy family in 1599 and was elected as a Member of Parliament for Cambridge in 1640, a position that catapulted him to power. England was on the brink of a civil war between factions supporting the monarchy (Royalists, or Cavaliers) and those supporting the power of Parliament (Parliamentarians, or Roundheads). Ultimately, the Parliamentarians prevailed, executing King Charles I and exiling his son, Charles II.

In the aftermath, the Parliamentarian victors declared a new Commonwealth. Cromwell led a military campaign into Ireland between 1649 and 1650 to crush Irish Catholics who supported the Royalists; his actions there are still seen as genocidal by some historians.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cromwell rose to the pinnacle of power in 1653 as the first Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. He died in 1658, perhaps of a malarial-type illness, according to The Cromwell Association, a historical society dedicated to Cromwell's life.

Despite the supposed abolition of the monarchy, Cromwell got a burial fit for a king: He was interred in Westminster Abbey, surrounded by velvet and spices, with Privy Council orders that "there ought to be an Inscripcion in a plate of Gold to be fixed upon his Brest before he be putt into the Coffin."

Grisly afterlife

Neither Cromwell nor the plate would stay in place for long, however. In 1660, with Cromwell dead and his son Richard forced to resign, Charles II returned from exile and retook the throne, restoring the monarchy. In January 1661, Charles II got his revenge. Cromwell was disinterred and taken to the town of Tyburn, where his corpse was ritualistically hanged, drawn and quartered — a parody of execution meant for postmortem humiliation.

The copper plate was passed down the Norfolke line and through private hands. Even more bizarrely, according to Sotheby's, Cromwell's head spent centuries out and about. It remained on a spike on Westminster Hall for two decades before blowing down and being taken by a sentinel. It was only in 1960 that the head was reinterred in Cambridge. Cromwell's body is likely in an unmarked grave near Tyburn, according to the Cromwell Association.

The copper plaque will be auctioned alongside other relics of history and literature, including a first edition of Charles Darwin's "On the Origin of Species" and the second edition of Shakespeare's plays, dating back to 1632.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.