Goodbye Y: Men Who Smoke Have Missing Male Chromosomes

Add another troubling side effect to the list of health issues caused by cigarettes: Smoking may cause the Y chromosome to disappear from men's blood cells.

A new study finds that men who smoke lose the Y chromosome in blood cells more frequently than nonsmokers — and the heavier their cigarette use is, the fewer Y chromosomes they have.

This Y chromosome loss could explain why male smokers are at higher risk of cancer than female smokers, the researchers said in their study, published today (Dec. 4) in the journal Science.

"The cells that lose the Y chromosome … They don't die," said study co-author Lars Forsberg, of the Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology at Uppsala University in Sweden. "But we think that they would have a disrupted biological function."

More specifically, the immune cells in the blood that are tasked with fighting cancer may be hampered without their Y chromosome, Forsberg told Live Science. [Macho Man: 10 Wild Facts About His Body]

The case of the missing Y

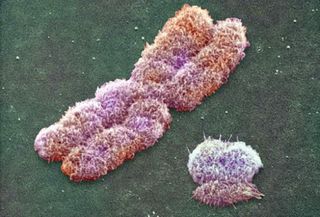

The Y chromosome is one of two sex-determining chromosomes in men, who have one X chromosome and one Y. (Women have two X chromosomes.) Normally, during cell division, copies of all of the chromosomes are made and sorted into the two new daughter cells. But during the complex process, chromosomes are sometimes lost, Forsberg said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Usually, a missing chromosome would result in the death of the new cell, but cells can survive without a Y chromosome.

Scientists have known for more than 50 years that Y chromosomes can vanish, Forsberg said. Missing Y's are more common in older men than in younger men. In April, however, Forsberg and his colleagues published findings in the journal Nature Genetics revealing that the loss of the Y chromosome in the blood cells is linked with an increased risk of cancer in men.

The next task, Forsberg said, was to find out what factors lead men to lose their Y chromosomes. He and his colleagues gathered health data from a total of 6,000 men who were participating in three different ongoing epidemiological studies in Sweden. The men were questioned on factors such as exercise, blood pressure, alcohol use and smoking, and also gave blood samples, so the researchers could test the prevalence of the Y chromosome in the blood. (Because red blood cells don't carry any DNA, the results apply only to the white blood cells, or immune cells, that circulate in the blood.)

Smoking's strange side effect

The results showed that it was very common for men in the study to be missing Y chromosomes from their cells. The men in two of the studies ranged in age from 70 to 80 years old. In the first group, 12.6 percent of men were missing Y chromosomes from their blood cells; in the second group, 15.6 percent had lost the Y chromosome.

The third group of men ranged in age from 48 to 93, and only 7.5 percent were missing Y chromosomes. The results from this group highlighted the effect of age, the researchers said. Among the men age 70 and older, 15.4 percent were missing Y chromosomes, compared with 4.1 percent of men younger than 70.

With those overall numbers established, the researchers compared participants on lifestyle and health factors and found that, other than age, only smoking was linked to the loss of the Y chromosome. Smokers had between 2.4 and 4.3 times the risk of losing Y chromosomes compared with nonsmokers.

More experimental work will be necessary to prove that smoking directly causes Y chromosomes to vanish — and to pin down exactly how cigarettes may bring about this side effect. But several clues in the results strongly imply that cigarettes are the culprit. For one, the men who smoked more had lost more Y chromosomes. And among men who had stopped smoking, the levels of Y chromosome in their blood were indistinguishable from those of men who never smoked.

That last finding is particularly encouraging, Forsberg said.

"When you stop smoking, these cell clones with loss of [the] Y [chromosome] will disappear from circulation," he said. In other words, the Y disappearance is reversible. [10 Scientific Tips to Quit Smoking]

Researchers aren't sure how widespread the smoking-related loss of Y is among other cells in the body; other studies of older men have suggested that Y chromosomes may disappear in other tissues with age, Forsberg said.

Cancer link?

The loss of the Y chromosome in the blood has little to do with manliness, despite the chromosome's association with sex.

"The Y chromosome is involved in much more than sex determination and reproduction," Forsberg said.

Instead, this vanishing chromosome could be the link that explains why men have a higher risk of cancer (from smoking, and in general) than women, Forsberg said. One possibility is that the missing Y is harmless in and of itself, but acts as a canary in a coal mine, signaling that cells are being damaged by smoking and accruing mutations that can cause cancer.

But Forsberg and his team believe the story may be more complex.

"Since we study blood cells from whole blood, it's basically the immune system that we study," he said. "One of the functions of the immune system is to fight cancer throughout life."

If some of the genetic code carried on the Y chromosome helps with this cancer-fighting function, the loss of the Y in blood could make the body more susceptible to tumors, he said. Next, the researchers plan to tackle immune cell types one by one, to find out which might be most affected by a missing Y chromosome.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.