Tao of Pandas: Sometimes They Go With the Flow

Sue Nichols is the assistant director of the Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability at Michigan State University. Nichols contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

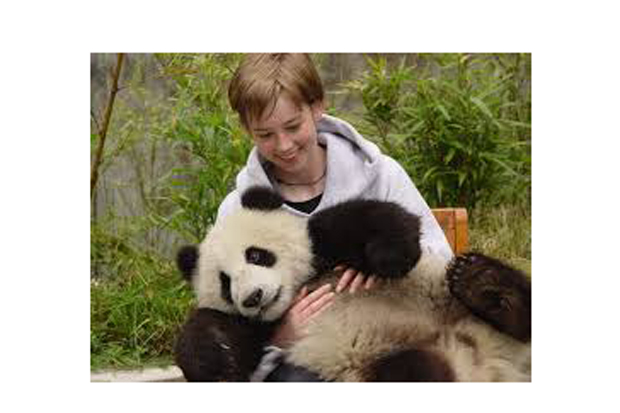

Good news on the panda front: Turns out, they're not quite as delicate — or as picky — as scientists had thought.

Until now, information gleaned from 30 years of scientific literature suggested pandas were inflexible about habitat. Those conclusions morphed into conventional wisdom, and then guided policy in China. But a Michigan State University (MSU) research associate recently led a deep dive into aggregate data and emerged with evidence that the endangered animal is more resilient and flexible than previously believed. [Pandas Show Resilience in Range of Habitats (Gallery )]

Plowing through panda data

Vanessa Hull is a postdoctoral researcher at MSU's Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability (CSIS). She spent three years studying giant pandas in China's Wolong Nature Reserve. Given the pandas' elusive nature, Hull had a lot of downtime. So she bided her time plowing through literature on panda habitat selection, and discovered inconsistencies and a lack of consensus on matters crucial for scientists and policymakers struggling to protect the estimated 1,600 giant pandas remaining in the wild. Those animals have been relegated to just 21,300 square kilometers (about 8,200 square miles). [Pandas' Latest Threat: Horses? ]

"Panda habitat selection is a complex process that we are still trying to unravel," said Jianguo "Jack" Liu, CSIS director. "Pandas are a part of coupled human and natural systems where humans have changed so much in [the pandas'] habitat."

What pandas need

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It has been thought that pandas demanded a forest with fairly gentle slope (easier to mosey around in while seeking bamboo), at a certain elevation, in original, old forest; an abundance of bamboo; and plenty of distance from people. Those recommendations, however, come from often-scant research, because pandas are difficult animals to study, Hull said.

"Pandas are difficult to observe and follow in the wild; we're always 10 steps behind them," Hull said. "We don't know why they're there — or where they were before and after. There's a lot of guesswork."

Hull and her colleagues analyzed the existing research and sought to separate studies that focus on where pandas live from studies that examine what kind of choices pandas make when multiple habitats are available. They discovered that pandas are not as selective as researchers once thought.

The research shows, for instance, that pandas are willing to live in secondary forests — forests that were logged and have since regrown. They also don't seem as selective about slope, and are willing to climb depending on which of the many varieties of bamboo is growing, or what type of forest it is in. The same flexibility exists for elevation and the amount of sunshine that hits a piece of panda home. The researchers also found a complex relationship between trees and bamboo: Pandas choose a range of forest types as places to spend their time, as long as bamboo is available.

Hope for the future

Those findings are good news. Indications that forests once cut clean by timber harvesting can return to acceptable panda habitat validate current bans on forest harvesting.

Hull said consensus would be helpful for future panda habitat research, since the future guarantees change.

"It's exciting to see the flexibility pandas have, or at least see that pandas are choosing areas I didn't think could support them," Hull said. "It gives you hope. They've survived throughout many challenges over so many millions of years; it would be sad to think humans came along and threw it all away. This also suggests we should stay on board and try to make things better for them."

The paper, "A synthesis of giant panda habitat selection," is published in the journal Ursus, a publication of the International Association for Bear Research and Management.

In addition to Liu and Hull, article authors include Gary Roloff, MSU associate professor of fisheries and wildlife; Jindong Zhang, a CSIS postdoctoral research assistant; Wei Liu, a CSIS alumnus; Hemin Zhang, Shiqiang Zhou and Jinyan Huang of the China Center for Research and Conservation of the Giant Panda in Wolong; and Zhiyun Ouyang and Weihua Xu of the State Key Laboratory of Urban and Regional Ecology, Research Center for Eco-environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. The National Science Foundation, NASA and MSU AgBioResearch have supported the work.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.