How Your Refrigerator Will Help Power the Future (Op-Ed)

Elizabeth Noll, Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) energy efficiency advocate, contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

You may not be an engineer or have X-ray vision that allows you to tell from looking at your appliances and electronics whether they are needlessly gobbling energy. Fortunately, you don't have to, because the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has established standards ensuring a minimum basic level of efficiency that all Americans can depend on for more than 50 types of products in their homes, businesses and industries.

In fact, for almost four decades, national energy efficiency standards for appliances and equipment have proven to be one of the most successful policy tools to reduce U.S. energy demand, lower emissions of climate-changing carbon emissions and other pollutants, drive new energy-efficiency technology innovation and save consumers billions of dollars every year, without sacrificing comfort or the performance of these products.

Those standards are the result of a great deal of input from manufacturers, energy efficiency advocates like NRDC, consumer groups, and many others. And, as a new NRDC fact sheet released today (Dec. 5) reminds, the standards have a bipartisan history dating back to 1987.

Efficiency without sacrifice

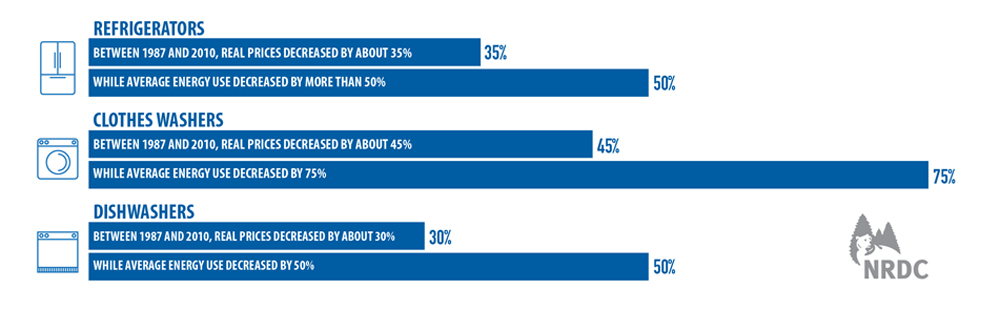

Whether we need a cold beer from the refrigerator or hot water from the shower, energy efficiency means using less energy while getting the same or better energy performance . Since the first efficiency standard was set for refrigerators, they have gotten bigger and quieter and added new features, all while keeping the lettuce fresh and energy bills down. In fact, refrigerators today use a quarter of the energy compared to those from the 1970s, all while offering 20 percent more storage and costing half as much.

The DOE Appliance Standards Program sets a basic minimum level of energy efficiency for products representing about 90 percent of home energy use, 60 percent of commercial building consumption and approximately 29 percent of industrial energy usage. In our homes, these products include common appliances like refrigerators, dishwashers, washers and dryers, and air conditioners. Standards also cover commercial and industrial equipment like electric motors and distribution transformers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The money saved

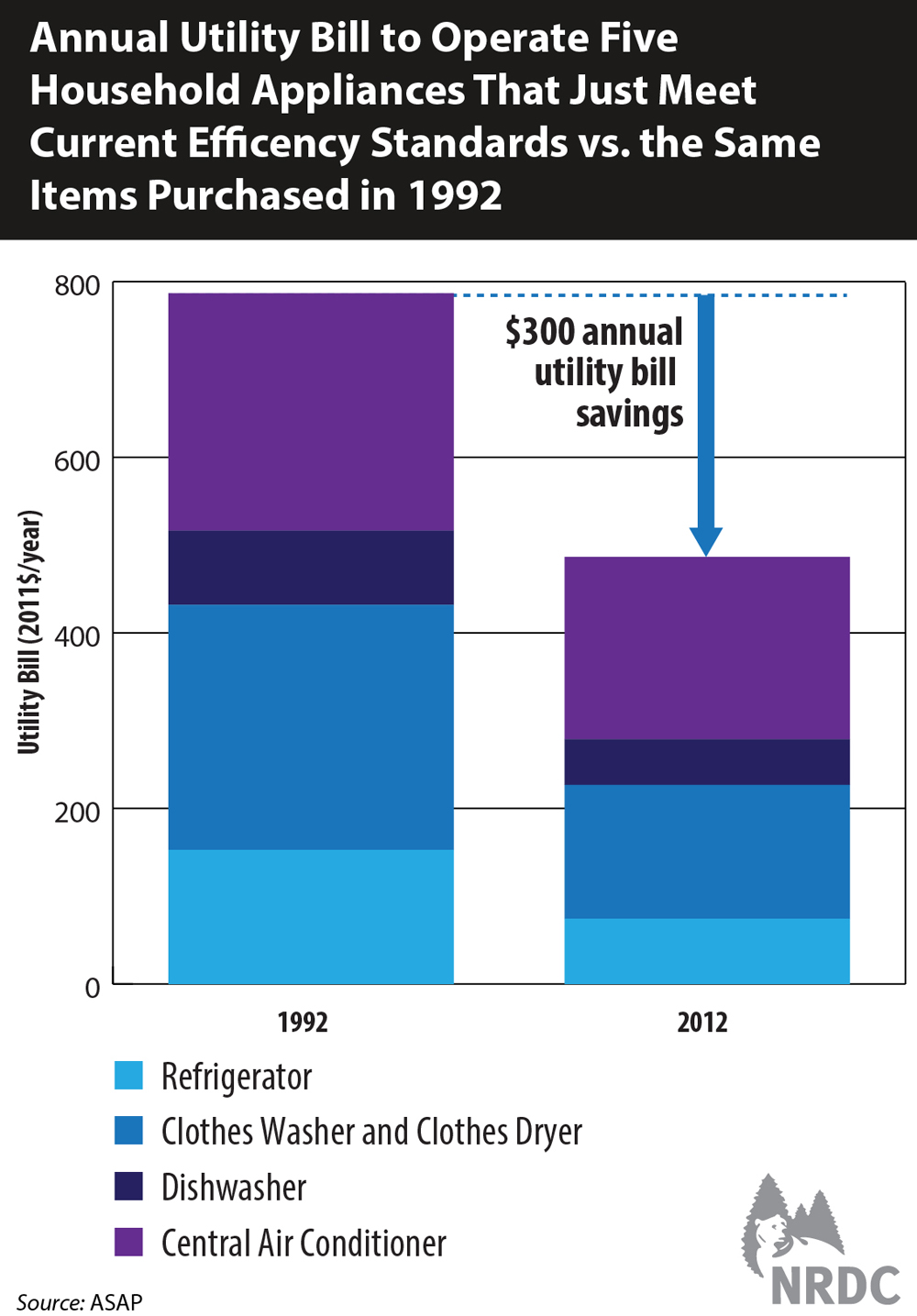

In total, these standards have created remarkable energy and utility bill savings for consumers . When comparing five typical household appliances that just meet the efficiency standard today with those same types of products purchased in 1992, homeowners save $300 annually on their utility bills, thanks to less energy waste. In terms of energy savings, new clothes washers use 75 percent less energy, and new dishwashers use half as much, as those from the 1987.

Rather than dictate a specific technology, the DOE sets a minimum level of energy-saving, leaving manufacturers free to innovate and find new ways to achieve even greater energy savings. In many cases, standards spur manufacturers to make technology advancements that reduce energy waste even more, which, in turn, creates new opportunities for improved minimum efficiency standards (and sometimes new jobs, as well).

The DOE is required to set standards at the maximum energy savings levels that are "technologically feasible and economically justified," meaning, among other things, that energy bill savings will outweigh any additional increase in product cost, often by a wide margin. To determine whether a standard meets those criteria, the DOE does extensive research, analyzes the market for each appliance, and determines the impacts to consumers, manufacturers and the U.S. economy.

The agency does that through an open and transparent process that allows for stakeholder input at multiple stages. While most standards work their way through a formal rule-making process, some standards are developed through consensus negotiations that bring together industry professionals and advocates.

Getting more than efficient

Although standards set a minimum "floor" for the smarter use of energy, manufacturers can — and do — go beyond that to cut their products' electricity and natural gas use even more. How do you find these products? There are labels that can help.

The yellow EnergyGuide labels found on many home appliances help consumers make informed decisions when buying new products. Required by the federal government on specific appliance types, EnergyGuide labels give information comparing similar models in terms of the efficiency level as well as how much products cost to operate and the annual energy used to run them. Manufacturers must use standard test procedures developed by the DOE to prove the energy use and efficiency of their products. The EnergyGuideallows consumers to compare similar products and see how they measure up.

In addition to the yellow EnergyGuide labels, consumers can look for the blue Energy Star designation on new appliances. Generally speaking, Energy Star represents the top 25 percent most energy-efficient models on the market. Although it's a voluntary program, it is widely recognized by consumers, which drives manufacturers to meet the efficiency benchmark in order to tout their products as qualifying for the coveted Energy Star designation. Some utilities offer rebates to consumers that purchase Energy Star appliances. Meanwhile, Energy Star recently launched a new category, called "Energy Star Most Efficient," that recognizes the truly best performers on the market due to their cutting-edge energy efficiency and the latest in technological innovation. [Energy Efficiency Making Good on its Promise (Op-Ed )]

EnergyGuide labels, Energy Star and minimum efficiency standards work together to encourage the market to greater levels of energy efficiency and help arm consumers with information on how to take control of bigger utility bills from energy-wasting appliances.

Standards lead to cleaner air, fewer brownouts

Improving the efficiency of the appliances and equipment in buildings in the U.S. can also significantly reduce the pollution that harms human health and the environment. America's power plants are the largest source of U.S. carbon dioxide emissions, responsible for roughly one-third of all domestic climate-changing pollution. If appliances and equipment use energy in a smarter way, power plants generate less power to run them.

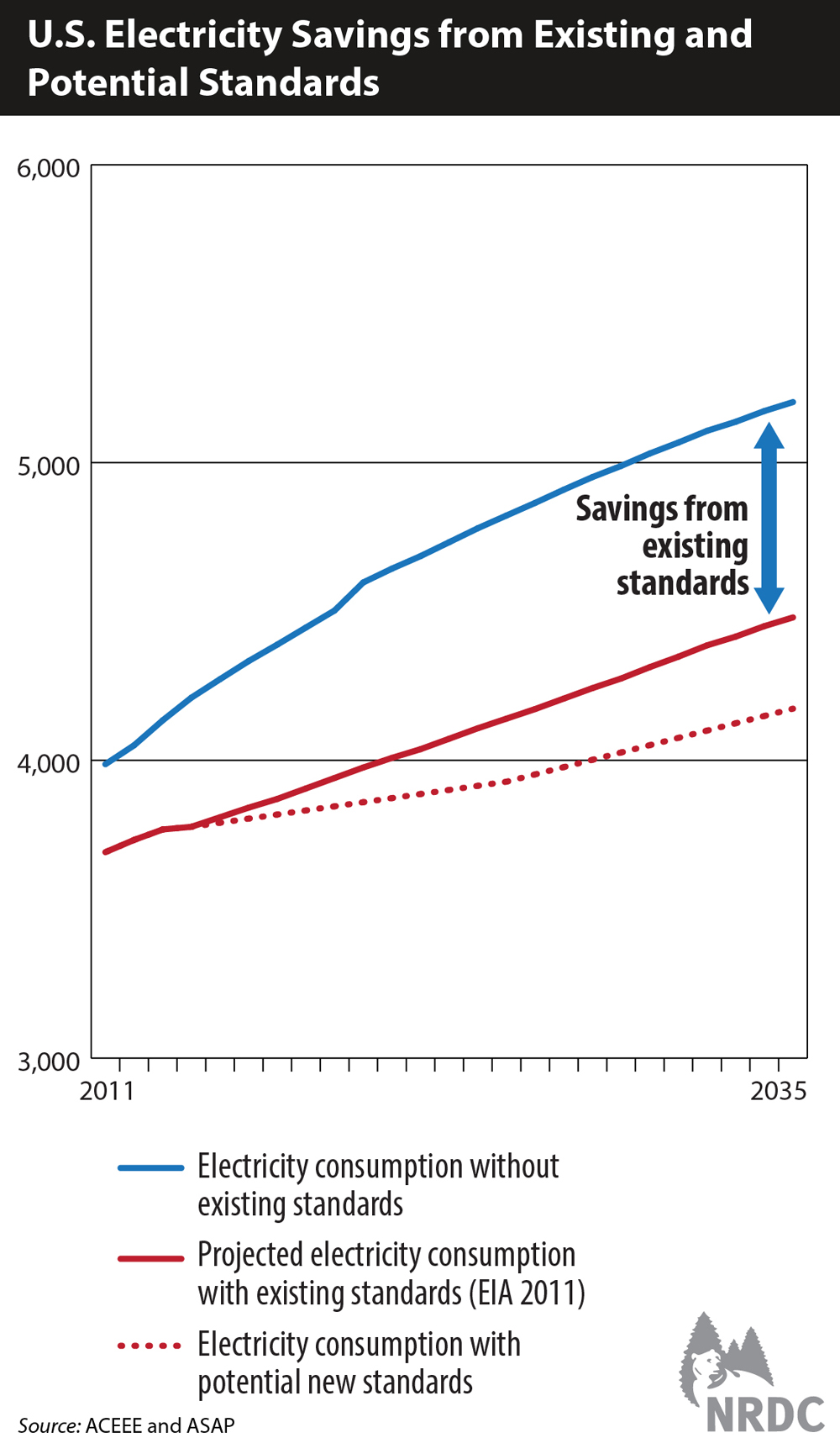

That saves billions on our energy bills and reduces America's carbon footprint. As a result of efficiency standards in place today, we will reduce carbon dioxide pollution by 470 million metric tons annually by 2035. That's equal to avoiding the pollution from 118 coal-fired power plants!

More efficient appliances also mean peak electricity needs — like on a hot summer day, when air conditioners are blasting away alongside all of our other appliances and equipment — will decrease by 240 gigawatts in 2035, more than twice the capacity of all the nuclear power plants in the United States. That will reduce the risk of rolling brownouts or blackouts, and allow homes and businesses to be more productive and resilient. Whether in a home, business or factory, energy that is burned without benefit is a waste.

National appliance standards cost-effectively save the U.S. a considerable amount of energy, lower emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants, and save consumers billions of dollars every year ($1.1 trillion in cumulative net savings by 2035), all while improving the environment. Looking forward, additional energy savings will appear as new product categories emerge due to technological progress and manufacturing ingenuity, and as standards for existing product categories are updated to reflect technology advancements.

So, next time you go to your fridge, you can feel good that standards have helped you save enough to pay for that six pack and plenty more — while ensuring a cleaner environment, too.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.