New 'Smart Skin' Could Make Prosthetics More Like Real Limbs

New prosthetic skin that is warm and elastic like real skin, and is packed with many different kinds of sensors, could one day help people with prosthetic limbs regain their sense of touch, researchers say.

In experiments, the researchers laminated "electronic skin" — prosthetic skin embedded with electronics — onto a prosthetic hand. They found that the skin could survive complex operations, such as shaking hands, tapping keyboards, grasping baseballs, holding hot or cold drinks, touching dry or wet diapers, and touching other people. The electronic skin proved to be as sensitive as expected to pressure, stretching, temperature and dampness, successfully relaying data rapidly and reliably, the researchers said.

The scientists included heating devices throughout the prosthetic skin that could make it feel at least as warm as a person's body temperature. Human skin is elastic, soft and warm, said study co-author Dae-Hyeong Kim, a biomedical engineer at Seoul National University in South Korea. "Our device has such properties," Kim said. [Bionic Humans: Top 10 Technologies]

In recent years, many research groups around the globe have been developing bionic arms and legs that could help patients replace lost limbs. Increasingly, scientists are looking for ways to connect these bionic limbs to human nervous systems, which could help restore patients' sense of touch as well.

But replicating the sensory capabilities of real skin has proven challenging. Recent efforts have aimed to develop smart prosthetics embedded with sensors, but those sensors were limited in either how sensitive they were, or how much data they could measure.

The new skin is exceptionally sensitive, and can sense a wide variety of data, such as information on temperature, humidity, stretching and pressure, the researchers said. It could help lead to "prosthetic devices for patients who lost arms, legs or skin," Kim added.

Typically, there are two factors that affect sensors' utility: how sensitive they are, and their dynamic range — that is, the range of data they can measure. "These two [factors] have an offsetting relationship to each other — high sensitivity usually results in a small range of measurements," Kim told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One problem with prior attempts to make smart prosthetics was that the sensors that were used were rigid, or semiflexible at best. This meant they could only flex a certain amount before fracturing, thus limiting the range of measurements they could make.

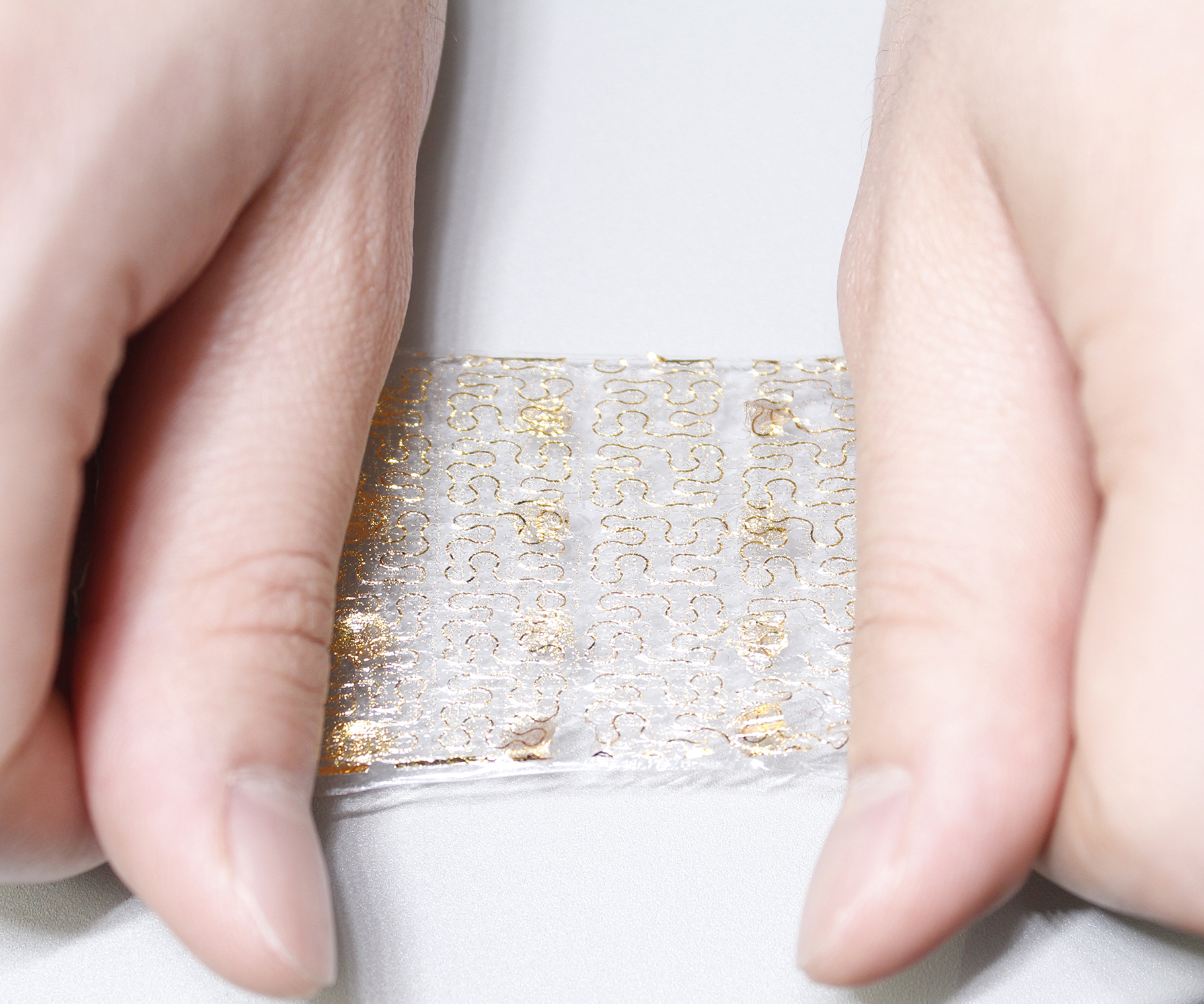

In contrast, the new skin uses sensors made of silicon ribbons that had a wavy, snake-like shape. This shape lets the sensors withstand more strain — that is, stretching — without breaking, and allows them to measure a greater range of data.

The researchers also noted that the prosthetic skin can stretch more on some parts of the body than on others. "Some parts of the hand stretch only several percent, while other parts [stretch] more than 20 percent," Kim said.

As such, the researchers matched the properties of the sensors on the electronic skin to how much stretching it would experience depending on which part of the body it covered. For instance, the researchers made the prosthetic skin more sensitive for the areas intended to cover parts of the hand where skin normally does not stretch much. But for prosthetic skin that covers parts where the skin would stretch a lot, they focused on improving the range of data they could measure.

In addition, the researchers aimed to make their prosthetic skin feel like real skin. "The feeling of artificial or prosthetic arms to other people who interact with the wearer of these devices is another important point to consider," Kim said.

The scientists also combined their electronic skin with an array of stretchable platinum electrodes that would stimulate nerves to relay sensor data to the brain. These electrodes were coated with microscopic particles of cerium oxide to help control the inflammation that such electrodes can trigger in the body. In experiments with rats, the researchers showed this electrode array could transmit data about the pressure of a touch to the brain.

However, there are still safety concerns about this electrode, such as the possibility that fractured electrodes could enter the bloodstream and cause damage, the researchers said.

In the future, the scientists hope to conduct more animal trials of their device. They detailed their findings online Dec. 9 in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.