Robot Swarm! NYC Exhibit Uses Bots to Teach Math

NEW YORK — A new interactive exhibit in New York City teaches kids and adults alike about the mathematical order of the natural world in an unconventional way: with dozens of swarming robots.

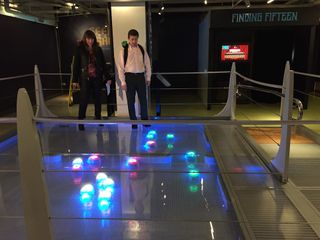

At first glance, the "Robot Swarm" exhibit — which opens Sunday (Dec. 14) here at the Museum of Mathematics (MoMath) in New York City — looks more like a futuristic boxing ring than a museum display. Essentially, it's an elevated box cordoned off by thick, metallic rope. At a preview of the exhibit, three people in backpacks (who happen to be MoMath's co-founders and chief designer) meander around the ring, performing what appear to be fancy footwork and exchanging mild smack talk. But no one throws any punches.

As the members of the trio move around, each is followed by a pack of tiny robots that roll around right under their feet. The robots, which look like an army of mechanical horseshoe crabs, are clearly visible through the exhibit's transparent floor. [The 6 Strangest Robots Ever Created]

The bots flash red, green or yellow depending on which backpack-clad human they're following at the moment. The mechanical army is in "pursue-mode." Each backpack contains a sensor that allows the robots to detect the location of the wearer. Once detected, the wearers are swarmed.

"In a swarm, the whole is more than the sum of its parts. There's almost no individual intelligence, but [the individuals] create this group intelligence because of the interaction of their behaviors," Glen Whitney, MoMath's other co-founder and co-director, told reporters Wednesday (Dec. 10) at a preview of the exhibit.

To make sure the individual robots' behaviors are part of a bigger picture, each bot maintains radio communication with a central computer, which dictates which of five different behaviors the bots should perform. At this week's demonstration, the bots pursue the people in the ring, but when in "run away" mode, the tables get turned, and the robots flee from the people in the ring. In "robophobia" mode, the robots flee each other, with each bot trying to get as far away as possible from its comrades.

All of these behaviors are examples of what Cindy Lawrence, MoMath's co-founder and co-executive director, called emergent behavior — a mathematical concept that helps explain how simple, local interactions can lead to large-scale organized behavior. You can see this concept at work in the exhibit, where robots appear to be carrying out some complex plan but are really just following one global rule, Lawrence said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For example, when the bots swarm around Lawrence's feet, the rule they're following is simple: get as close to the sensor as possible.

In the real world, many tasks performed by robots are (or soon will be) aided by an understanding of emergent behavior. The ultimate goal for those who study robots in this context is to understand the relationship between the bots' simple, local interactions and their complex group behaviors, said James McLurkin, a professor of computer science at Rice University in Texas, and one of MoMath's roboticists in residence.

"The Holy Grail is to identify some global goal and then somehow get all these robots to get it done," McLurkin told Live Science. "And you, the human, never have to specify the actions of each individual robot."

McLurkin helped MoMath get 24 bots to accomplish global goals for the Robot Swarm exhibit, and he's done the same thing with at least 100 robots in his lab at Rice. Michael Rubenstein, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University, has figured out how to get 1,000 little robots to perform simple group tasks, such as moving around to form a particular shape.

In the natural world, thousands of creatures coordinate more complex behaviors than Rubenstein's bots perform — like avoiding a predator, or building a hive. Fish, honeybees, wolves and geese are some of the many animals that exhibit individual behaviors that allow them to act in concert with their peers, Lawrence said. And it was these examples from the natural world that inspired Robot Swarm.

"Math problems in schools don't always feel realistic to kids," Lawrence told Live Science. "We want kids to see that math has a relationship to the natural world. Math is all around us."

Robot Swarm opens to the public on Sunday (Dec. 14).

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science .

Elizabeth is a former Live Science associate editor and current director of audience development at the Chamber of Commerce. She graduated with a bachelor of arts degree from George Washington University. Elizabeth has traveled throughout the Americas, studying political systems and indigenous cultures and teaching English to students of all ages.