E-Cigarettes May Lure Teens into Traditional Smoking

Teens who use e-cigarettes don't have as many of the characteristics typically seen in teens who smoke traditional cigarettes, such as impulsiveness or having behavior problems at school, according to a new study.

The finding could indicate that advertising and the availability of e-cigarettes is drawing in kids who wouldn't have otherwise picked up any kind of cigarette, the researchers said.

In the study, teens who were "dual users," meaning they smoked both regular and e-cigs, had many risk factors for smoking, whereas those who smoked neither traditional nor e-cigarettes had very few. The e-cigarette-only users fell somewhere in between. (Kids who smoked only traditional cigarettes were very rare, making up about 3 percent of survey respondents.)

"We were kind of expecting that e-cigarette users would look like the smokers, but that's not really what happened," said health psychologist Thomas Wills, of the University of Hawaii Cancer Center in Honolulu, who led the study.

E-cigarette users, Wills said, "are a little bit elevated on risk, but relatively low. That's a new finding."

E-cig debate

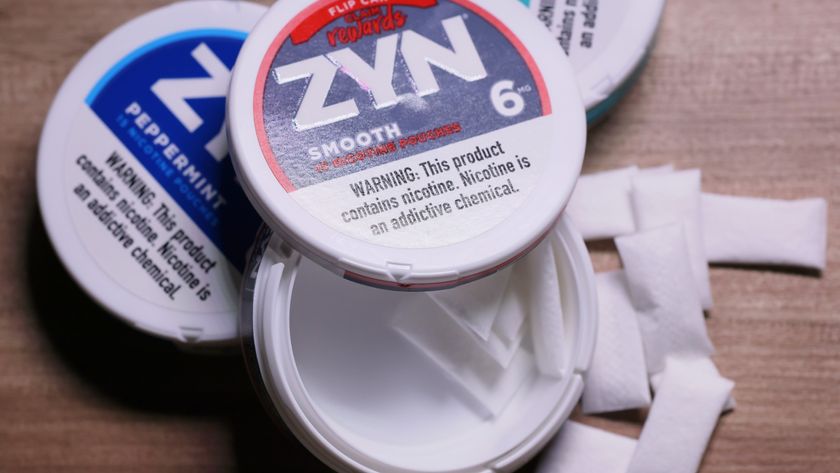

E-cigarettes, or electronic cigarettes, are handheld vaporizer devices that deliver nicotine to the user via a fine aerosol mist. They're an object of controversy in the public health world, with some researchers arguing that they could help smokers to quit while providing a safer nicotine-delivery system, similar to nicotine gums or patches. But others point to studies like the one published in September 2014 in the journal Cancer, which found that e-cigarette users were twice as likely to fail at quitting smoking compared with those who tried to quit without the help of e-cigarettes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Regardless of e-cigarette's role in the battle to quit smoking, their use is way up among both adults and teens. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention's National Youth Tobacco Survey has found that 10 percent of high-school students tried e-cigarettes in 2012, up from 4.7 percent in 2011. [Infographic: How E-Cigs Work]

With little data available on why teens use e-cigarettes, Wills and his colleagues decided to investigate. They surveyed 1,941 ninth- and 10th-graders from three public and two private high schools on the island of Oahu, asking the teens about their use of e-cigarettes, traditional cigarettes and other drugs and alcohol.

The researchers also asked about known risk factors for cigarette smoking, such as rebelliousness, impulsiveness, academic performance and home life.

The first finding that jumped out was the high rate of use of e-cigarettes by Hawaiian high schoolers, Wills told Live Science.

National studies have found that about 12 percent of teens say they have ever used e-cigarettes, he said. "What we found here is about 29 percent."

E-cigarettes are heavily advertised in Hawaii, and traditional cigarettes are also heavily taxed, making e-cigarettes a thriftier option, Wills said. E-cigs everywhere may contain flavored nicotine, and in Hawaii, manufacturers use tastes that appeal to the tropical flavors teens may know best: mango, papaya and pineapple.

Gateway to smoking?

The researchers also found that among teens in the study, the risk factors themselves for e-cigarette use were similar to risk factors seen in teens everywhere. Kids with higher levels of impulsiveness, or less parental support, for example, were more likely to smoke, the researchers report today (Dec. 15) in the journal Pediatrics. [10 Scientific Tips to Quit Smoking]

The finding that kids with fewer of these risk factors may pick up e-cigarettes imply that the devices might bring kids to smoke who would have never picked up a traditional cigarette otherwise, Wills said.

"We can't prove that, but certainly our data are consistent with that possibility," he said. He and his team hope to conduct a long-term study of Hawaiian high schoolers to see if e-cigarettes lead to greater levels of traditional smoking.

At least some research already conducted suggests that Wills and his colleagues might be right. A study published Nov. 28 in the journal Nicotine & Tobacco Research found that sixth- through 12th-graders who had used e-cigarettes were more willing to try traditional cigarettes than those who hadn't. When asked if they would smoke a cigarette if offered by a friend, 43.9 percent of e-cigarette users in the National Youth Tobacco Survey said they would do so, compared with 21.5 percent of the teens who had never used e-cigarettes.

Those results can't definitively answer the question of whether the e-cigarette use led kids to try traditional tobacco, but the potential is there, said Rebecca Bunnell, the study leader and associate director of science for the Office of Smoking and Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bunnell and her colleagues were also alarmed to find that among youth who had never smoked traditional cigarettes, e-cigarette use tripled between 2011 and 2013, with an estimated 250,000 otherwise non-smoking teens using e-cigarettes.

"Whether or not they're a gateway, their use in and of itself is a concern, because they contain nicotine," Bunnell told Live Science. Nicotine itself can cause both short- and long-term changes in the adolescent brain, she said. According to a 2012 review in the journal Cold Springs Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, teen exposure to nicotine can interfere with the development of the prefrontal cortex, the seat of self-control.

Because this brain region does not finish maturing until people reach their early 20s, the researchers wrote, teenagers are also more susceptible than adults to nicotine's addictive effects.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.