Climate Accord Struck In Lima; Key Decisions Postponed

LIMA, Peru — In the early hours of Sunday morning, bleary-eyed dealmakers from nearly 200 countries and the European Union set a framework for an agreement that would take an unprecedented approach to slowing climate change. Critically, however, they also delayed a host of decisions until next year, which could make reaching a landmark pact even more difficult.

The Lima Accord, a four-page document, was adopted by climate negotiators a little after 1 a.m. ET Sunday. It was unanimously agreed upon following talks that were at times acrimonious and concluded more than 30 hours behind schedule.

While member countries tacitly agreed to curb their rates of greenhouse gas emissions, a raft of things weren’t decided, adding hurdles to securing a truly global climate agreement in Paris next December.

A large schism separated wealthy states and developing nations before negotiations ever began in Lima, and on many fronts, those divides remain. Rich and poor countries could not agree on language to resolve issues like financing for climate adaptation or compensation for damage inflicted by climate change. Nor could they agree on the groundrules to determine each country’s commitment to cut carbon pollution or whether to make those commitments legally binding under international law.

The four-page document they were left with was still groundbreaking in its scope, but it left a lot of work to be done ahead of the conference in Paris.

Document Language

Around lunchtime on Saturday, a draft of a decision that the U.S., the European Union and other wealthy states wanted adopted was rejected by representatives of China, African nations, and other poor and developing nations, angry that issues important to them had been omitted. Following renewed closed-door haggling and redrafting, meeting leaders presented delegates with a substantially rewritten document as midnight neared, one containing references to the issues important to the developing world, such as climate adaptation and financing. Those references, though, were couched in vague and noncommittal language.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To ministers and other delegates who were worn out, worrying about other commitments and flights back home, and desperate to salvage the talks from what America’s negotiating team described as the threat of a “major breakdown,” such language proved good enough.

Kerry: Agreement Essential To Overcome Climate Threat Climate Financing ‘Not Possible’ For Governments Alone Giving Climate Pact Legal Teeth Could Make It Toothless What’s At Stake in Lima Climate Talks

Developing nations, for example, wanted wealthy ones to lay out a plan at Lima for how they would satisfy a 2010 commitment to “mobilize” $100 billion a year by 2020 to help them adapt to climate change and reduce their climate impacts. Instead, the decision that was adopted “urges” developed countries to “provide and mobilize enhanced financial support” for “ambitious mitigation and adaptation actions” by the developing world.

Oxfam Australia economic justice coordinator Kelly Dent described that language as “really disappointing.” She said she feared it would allow developed countries to continue to use “financing as a bargaining chip” up until the December 2015 meetings in Paris.

Similarly contentious was the compensation sought by developing countries for damage inflicted by climate change, known as “loss and damage;” to decades-old distinctions under the next climate agreement between rich and poor countries, known as the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities; and to priorities surrounding efforts to adapt to climate change.

Those issues weren’t whittled out of the Lima decision, as developing countries feared. Nor does the text adopted in Lima make any new or firm commitments to them. Rather, decisions regarding specifics were widely deferred until next year.

Many delegates from developing countries characterized the accord as a victory — something that has been relatively rare during 20 years of international climate negotiations.

“China and India worked very actively together, and therefore we could achieve success,” Indian negotiator Prakash Javadekar told journalists outside the meeting room Sunday morning. “We look toward Paris with hope that the same spirited cooperation will continue.”

Coming Next Year

An agreement reached in Paris could become the most significant climate pact since a protocol was finalized in Kyoto, Japan in 1997. But the dearth of meaningful decision-making during the exhausting Lima round of talks means the negotiations in Paris, and during lower-level rounds of talks planned before the Paris meeting, will need to resolve yawning disagreements between rich and poor nations if a forceful agreement is to be realized.

Poorer nations generally want the agreement to touch on a wider range of issues than do wealthier ones, which would prefer to focus on efforts to rein in greenhouse gas pollution.

“Countries will have to push even harder next year if we are to get an agreement that shows the world that our leaders want to be on the right side of history,” Jake Schmidt, director of international programs at the Natural Resources Defense Fund, said.

“Countries know that they are going to have to come forward with strong commitments next year to curb their carbon pollution,” Schmidt said. “Nobody questions that fact anymore. The only question is how aggressive will they be, and how they will be captured in a new legal agreement?”

It won’t be clear until next year, after nations have declared how they plan to contribute to a new post-2020 global climate action plan, how effective the upcoming agreement might be in slowing global warming. But foreshadows of commitments outlined so far by the world’s biggest polluters make it clear that it won’t come close to limiting warming to within the goal of 2°C, or 3.6°F. Negotiators hope subsequent pacts will achieve that goal.

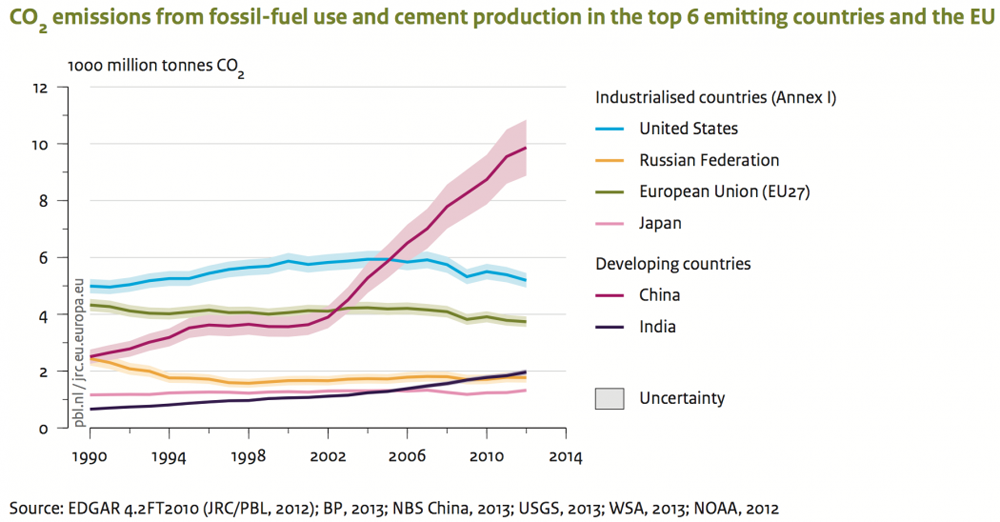

The U.S. has indicated that it will commit to produce 26 to 28 percent less climate-changing pollution in 2025 than was the case in 2005. China has said it plans to stop its growth in annual greenhouse gas pollution rates by 2030. The EU has resolved to reduce its pollution by 40 percent between 1990 and 2030.

The surprise joint announcement of such targets by President Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping a month ago raised spirits during the Lima climate talks. So, too, had a recent flurry of national pledges to the Green Climate Fund, which is the body set up to administer the promised $100 billion in annual climate financing for poorer countries by 2020.

Ground Rules Scant

It is the nature of these commitments, which are known as intended nationally determined contributions, or INDCs, that will help to clearly set the post-2020 climate agreement apart from the Kyoto Protocol — a protocol that proved largely ineffective. Instead of imposing the same pollution reduction requirements on a few dozen industrialized countries, the Paris agreement will call on all countries and the E.U. to meet contributions that they set for themselves toward meeting global climate action.

One of the top priorities for the Lima talks was to establish ground rules for the INDCs. In the end, though, what could have been ground rules were instead enshrined as suggestions.

The Lima Accord states that countries “may include, as appropriate,” timeframes of their INDCs and estimates of their expected benefits, along with how they consider them to be “fair and ambitious.” That represented a weakening from a previous draft, which earlier Saturday had catalogued information that “shall” be provided.

The U.S. had been pushing for a process in which nations could review each other’s INDCs next year; something that was opposed by China. Again, China won out. Instead of intense international scrutiny of INDCs next year, the U.N. will produce a synthesis report by early November that estimates their “aggregate effect.”

Lead U.S. negotiator Todd Stern spoke in upbeat terms after the accord was adopted, applauding that “transparency requirements” had been adopted for the INDCs.

“The Lima Accord for Climate Action delivers what we need to go forward,” Stern said in his speech in the meeting room following adoption of the accord. “It wasn’t always easy guiding this decision to a safe landing.”

Legal Uncertainty

What the negotiators couldn’t come close to agreeing upon, however, was whether the INDCs should be legally binding under international law. That decision may be made next year.

The European Union has been pushing for INDCs to be legally binding under international law. That, however, would require any agreement struck in Paris to be ratified as a new treaty by governments, which is something that would be nearly impossible for the U.S. to do, given the high proportion of members of Congress who oppose climate action. American negotiators would prefer to see states commit to pollution reductions using domestic laws, something that the Obama Administration is already doing as it uses the Clean Air Act to tackle pollution from power plants, vehicles and other sources.

Leaving that key legal question unresolved will create uncertainty for nations as they prepare to formally announce their INDCs next year.

“There are some who say that a legally binding agreement shows the strongest signal of commitments from nations that they take this issue seriously,” Alex Hanafi, an Environmental Defense Fund attorney involved with the talks, said.

“The potential downside of that is that some nations may be less willing to put forward an ambitious target if they feel they’re going to be held legally accountable, or be punished in some way if they do not reach that target,” Hanafi said.

An Opus of Indecision

The slimness of the four-page decision that was adopted Sunday contrasted with the textual corpulence of a 37-page partner document, which had been thrashed out by negotiators by Wednesday, listing alternative options for a long list of decisions that were left unmade in Lima.

Some alternatives listed in the partner document, known as the elements text, for example, deal with potential longer-term efforts to prevent the globe from warming more than 2°C compared with pre-industrial times. One of the options to be considered next year would be to commit to reducing annual greenhouse gas emissions globally by 40 to 70 percent in 2050, compared with 2010 levels, and for emissions to be “near-zero” by the end of the century.

Other alternatives discussed in the elements text relate to how climate adaptation goals could be set and assessed, and some deal with climate financing.

Stern pointed to this partner document earlier on Saturday while trying to convince delegates from developing countries to agree to the previous proposed Lima agreement.

“Every issue that people are arguing about here in this room today is preserved in the draft elements text,” Stern said. “You are not compromising your positions if this text stays neutral on your issues.”

In the end, Stern appears to have taken his own advice, leading the U.S. to relinquish some of its priorities in a substantial compromise.

The non-committal approach of relinquishing to a thick elements text may have helped secure accord in Lima. But it will make it more difficult for negotiators to hone in on the historic and potent new climate agreement they hope for in Paris next December.

You May Also Like: ‘Nuff Said: CO2 Emissions Plan Moves to Next Step CO2 Takes Just 10 Years to Reach Planet’s Peak Heat WMO Warns Lima Delegates 2014 May Be Hottest Year Clues Show How Green Electricity May Be in 2050 Report Maps Out Decarbonization Plan for U.S. News of Obama Climate Pledge Caps Epic Week

Originally published on Climate Central.