Violent Volcanic Blasts Ripped Through Antarctic Ice Sheet Twice

SAN FRANCISCO — Volcanoes punched through a remote part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet twice in the last 50,000 years, according to research presented Monday (Dec. 15) here at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Distinctive layers of brown ash in a deep ice core are evidence of violent volcanic explosions that occurred about 22,470 and 45,381 years ago, near the West Antarctic divide. Their source, however, is a mystery.

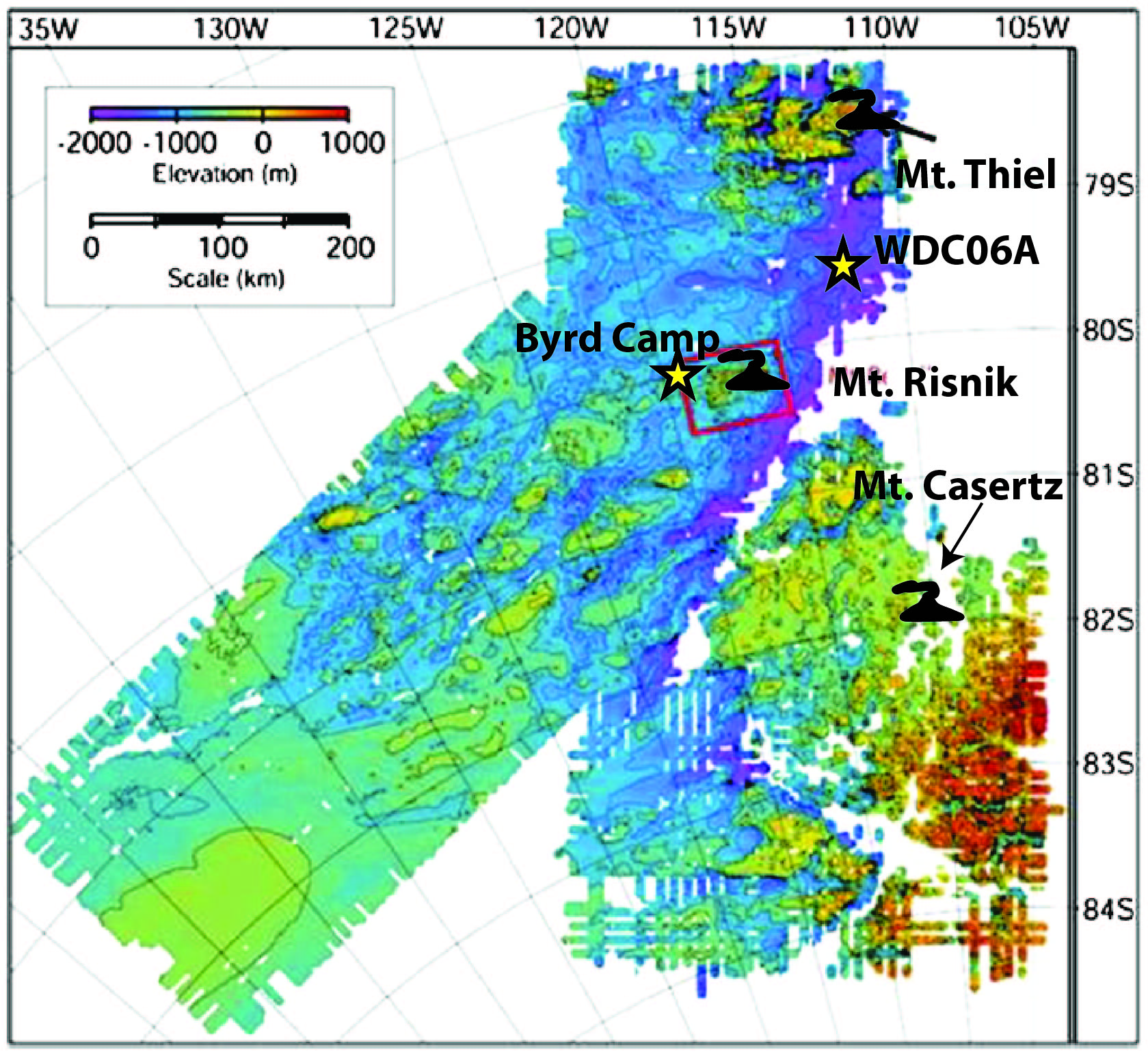

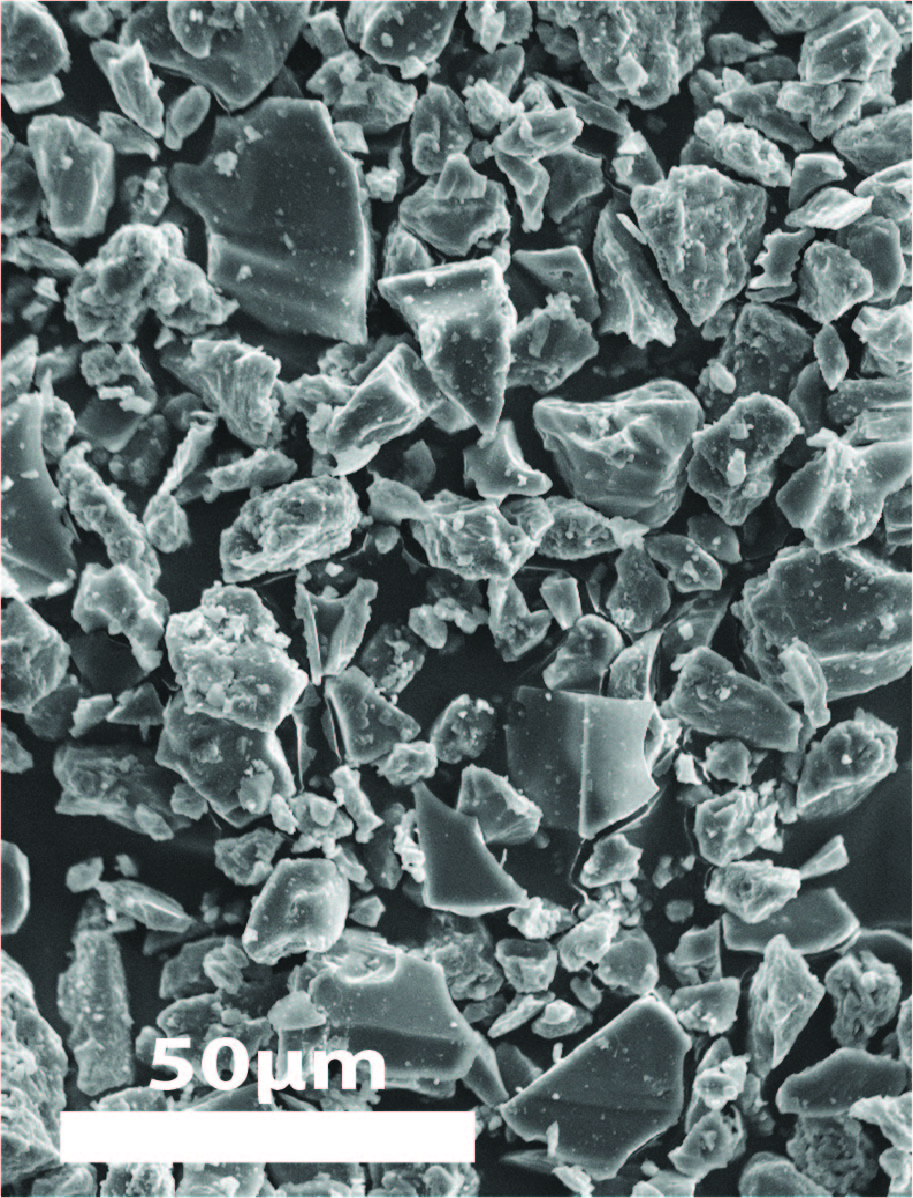

The closest active volcanoes that rise above the ice are more than 185 miles (300 kilometers) away, said study leader Nels Iverson, a volcanologist and graduate student at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology in Socorro. Powerful eruptions from these peaks have dusted the West Antarctica divide with ash, leaving glassy shards embedded in younger layers of the ice core. However, the ash particles described here Monday are too blocky and coarse to travel long distances, even on Antarctica's fierce winds. The ash is also chemically different from eruptions at the distant volcanoes. And to draw the circle in tighter, neither ash layer appears in an ice core drilled about 60 miles (100 km) to the southeast. [Fire and Ice: Images of Volcano-Ice Encounters]

"It had to be from somewhere close," Iverson told Live Science. "Ash particles that travel far are shaped like little parachutes. These are like your fists trying to float on air."

Iverson said the rough, glassy shards embedded in the ice are typical of phreatomagmatic eruptions, the spectacular outbursts that occur when lava meets water. This kind of eruption killed 57 people at Japan's Mount Ontake volcano in September, when water was superheated to steam. Similarly, when lava emerges under glaciers or ice caps, the molten rock melts ice into water and explodes, shattering lava into microscopic bits and flinging ash into the air.

Depending on the ice thickness and eruption size, it's possible for volcanic eruptions to have penetrated the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, said volcanologist Ben Edwards of Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, who was not involved in the study.

Magmas such as the basanite (an igneous rock) from the 45,000-year-old ash layer can melt three to six times their own mass in ice, he said. "The key thing is ice thickness," Edwards said. "Really thick ice makes it more difficult for the magma to explode."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Iverson suspects the volcanic source is buried close to the divide, where the ice sheet is more than 10,000 feet (3,050 meters) thick. There are three volcanoes entombed in ice within about 125 miles (200 km), and even more could be present.

Earthquakes suggest magma still churns beneath a previously unknown subglacial volcano in West Antarctica's Executive Committee Range, which was uncloaked when shaking started in 2010. Gravity and magnetic anomalies hint at nine subglacial volcanoes near the West Antarctic divide, John Behrendt, a geologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder reported today (Dec. 17) at the meeting. Behrendt was not involved in the ice core study.

If a volcano erupts under the ice sheet, it could melt out millions of gallons of water, possibly destabilizing major glaciers. However, scientists don't yet agree on the potential effects of a subglacial eruption.

"We're trying to understand the implications for the stability of the ice sheet," Iverson said.

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet grew up and around an abundance of active volcanoes. For instance, the coastal volcanoes Mount Berlin, Mount Takahe and Mount Siple have erupted some 20 times in the past 571,000 years, according to ash layers in ice cores. Geothermal heating has cooked the bottom of the ice sheet in the vicinity of some ice-covered volcanoes, according to recent studies. For instance, at the West Antarctic divide drilling site, researchers recovered about 70,000 years of ice, not 100,000 years as was expected, because the bedrock was hotter than they had assumed.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.