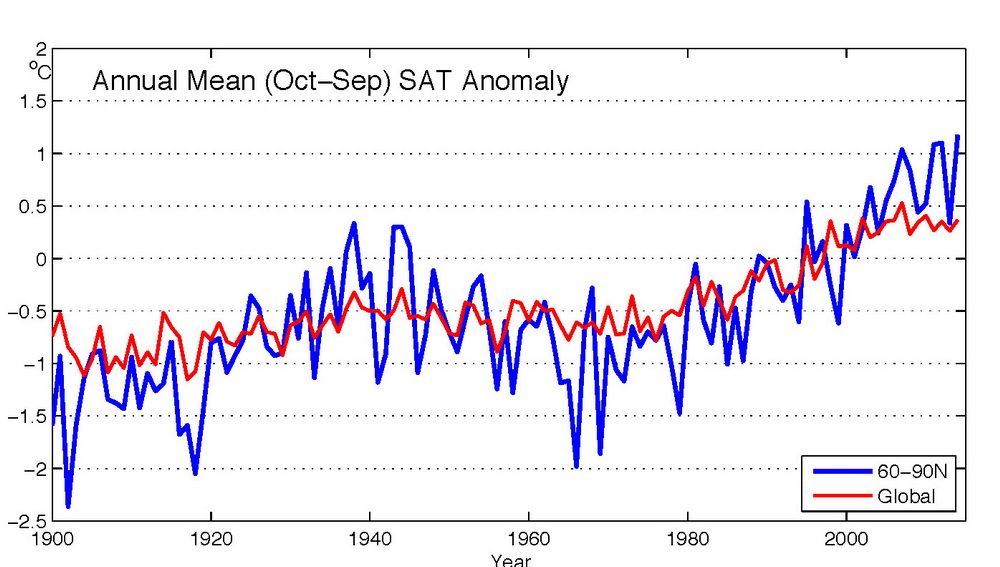

Arctic Is Heating Up Twice as Quickly as Rest of World

Bad news for polar bears: The Arctic is still warming at twice the pace of the rest of the planet, according to a new federal report.

Last year, air temperatures in the northernmost regions of the globe were, on average, 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) higher than normal. Unusually warm years like 2014 have only become more frequent in the Arctic in the past decade, even as the rate of temperature increase slowed for the rest of the world.

In 2014, the Greenland Ice Sheet's heat-deflecting brightness hit a low; spring snow cover dwindled to record lows in Eurasia; polar regions had a below-average extent of summer sea ice, and as for the polar bears that depend on that ice to survive, some populations have declined, according to the report. [See Stunning Photos of Earth's Vanishing Ice]

The findings are included in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association's (NOAA) annual "Arctic Report Card," a comprehensive review of the North Pole's health that is assembled by more than 60 scientists.

"Climate change is having a disproportionate effect on the Arctic," Craig MacLean, NOAA's acting assistant administrator for the office of oceanic and atmospheric research, said in a news briefing today (Dec. 17) at the 47th annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. "For the past 30 years, the Arctic has been getting greener, warmer and increasingly more accessible to shipping, energy extraction and fishing."

A trend of warming

Unlike past report cards, this year's polar checkup didn't reveal any major broken records. But this year's data fits in with the "persistent warming" trend that scientists have been observing in the Arctic for more than three decades, said Jacqueline Richter-Menge, of the U.S. Army's Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

From October 2013 to September 2014, the average surface air temperature in the Arctic was 1.8 degrees F (1 degree C) above the 1981-2010 average. The amount of sea ice floating in the Arctic in September 2014 was the sixth lowest since satellites began recording such data in 1979, the report found. Though the Greenland Ice Sheet had essentially the same mass in 2014 as it did in 2013, its reflectivity, or albedo, hit a record low in August. (Records only began for this effect in 2000.)

The Arctic warms at a higher rate than lower latitudes because of a well-documented effect known as Arctic amplification of global warming, Richter-Menge told reporters. Arctic amplification is a self-feeding cycle. Because of their light color, sea ice and snow bouncs radiation from the sun back into the atmosphere. But when more ice and snow melta, more of the dark-colored patches of earth and ocean are exposed, locking more heat into the already-warming planet's surface.

Kinky jet streams and missing polar bears

Rising temperatures in the Arctic are thought to affect the rest of the planet. Some research has suggested that warming around the North Pole can cause the typical path of the jet stream to go haywire, though scientists have yet to reach a consensus. Without data for a long period of time, it's difficult to tell whether this phenomenon is really a trend or part of the "normal chaos" of the atmosphere, said James Overland, an oceanographer with NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory. Regardless of the cause, a wavy jet stream can have a huge influence on weather, the report illustrates. For example, a twisted jet stream led to remarkable temperature spikes in Alaska in January, when the region experienced temperatures as much as 18 degrees F (10 degrees C) higher than normal.

This year's Arctic Report Card also included a special paper on polar bears that found the species has experienced a major decline in Hudson Bay, Canada, because of sea-ice loss. (Bears use these floating ice platforms to travel, hunt and look for mates.) The number of females in this region dropped from 1,194 to 806 between the years 1987 and 2011.

But, the news was sunnier for polar bears in other regions. For example, the population of polar bears in the Beaufort Sea, north of Alaska, declined by as much as 50 percent a decade ago. But now, the population seems to have stabilized at about 900, according to the report.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.