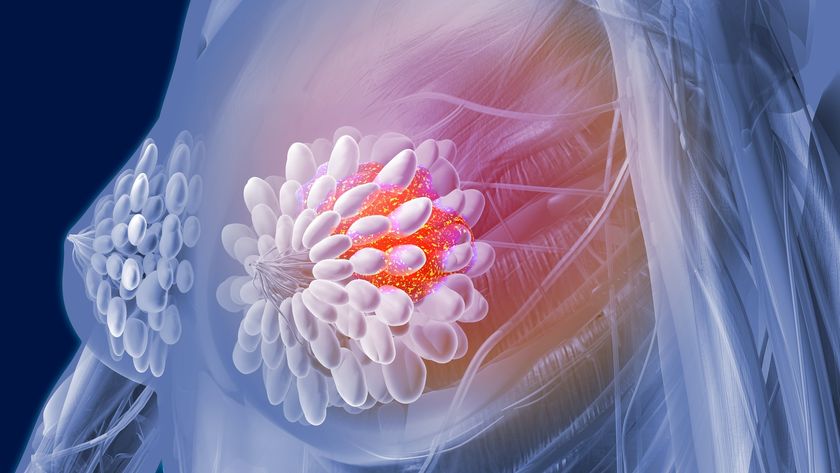

For Some, Less Radiation for Breast Cancer Makes Sense (Op-Ed)

Dr. Lucille Lee is an attending physician in the Department of Radiation Medicine at North Shore-LIJ's Cancer Institute and is a board-certified radiation oncologist specializing in the treatment of breast and prostate cancer. She specializes in multiple techniques including partial breast irradiation and breast hypofractionation. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Once physicians are accustomed to practicing in a certain way, changing that paradigm can be difficult to embrace — even when scientific evidence increasingly supports the change.

That's likely what's holding back more radiation oncologists in the United States from implementing a shorter course of radiation therapy for early-stage breast cancer patients who've undergone breast-sparing lumpectomy surgery. New research published in the Journal of the American Medical Association indicates that two-thirds of these U.S. patients are still receiving six to seven weeks of radiation therapy after a lumpectomy instead of a shorter course of radiation that's been shown to be just as effective.

Four prior published studies, as well as practice guidelines from the American Society for Radiation Oncology, support a three-week course of radiation known as hypofractionated whole-breast radiation therapy designed to reduce the risk of a cancer returning. The shorter treatment uses higher individual doses of radiation, but comes with similar side effects to the longer radiation course.

As I've seen time and again in my own career in radiation oncology, breast cancer patients who are the best candidates for a shorter course of radiation treatment can really benefit from its advantages. Not only is the abbreviated therapy less expensive (whether paid for by insurance companies or the patient), but it's also far more convenient.

Radiation therapy typically involves daily hospital visits , so cutting the total number of these visits essentially in half means less stress and disruption to everyday life. Many of these women have careers and children at home needing care, meaning those front-and-center obligations aren't displaced so drastically in order to receive daily radiation therapy.

The new JAMA research, analyzing millions of cases, found that in 2013, only 34.5 percent of early-stage breast cancer patients over age 50 underwent the shorter hypofractionated radiation. But that was a substantial increase from five years earlier, when research had shown that roughly 1 in 10 of these women were getting the shorter course of therapy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other countries have been quicker to adopt the newer treatment, with the JAMA research noting that more than 70 percent of Canadian early-stage breast cancer patients were already receiving hypofractionated radiation therapy by 2008.

The shorter course of therapy, however, may not be the right choice for every early-stage breast cancer patient who had lumpectomy surgery. Since research hasn't sufficiently focused on patients under age 50, we don't have enough evidence to understand whether the abbreviated radiation is just as effective for them as the longer therapy. Also, women with larger breasts may not be optimal candidates for hypofractionated radiation.

How can early-stage breast cancer patients find out they're eligible for the shorter course? Increasingly educated on medical matters, patients need to speak up and ask their doctors. And physicians themselves need to accept that feeling comfortable about how they have practiced medicine for so long doesn't justify holding on to outdated ideas.

In this case, it's quite clear that fewer radiation treatments can be just as effective for early-stage breast cancer patients as the "traditional" longer course. When patients receive more therapy than they actually need, it's no longer therapeutic — it's simply overdone.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.