'Captain America' to 'Interstellar': The Science of 2014's Sci-Fi

From intelligent machines to intelligent apes, and from alien plant creatures to wormhole-hopping spacefarers, the sci-fi movies of 2014 brought a heap of science tidbits to the screen. Here are the 12 best science nuggets from the last 12 months of science-fiction films:

January: "I, Frankenstein" shows how science blurs life and death

In January, "I, Frankenstein" added a dose of supernatural to the traditional Frankenstein story (the monster battles legions of demons, for example). But the move also stuck to the classic novel's origin story: As in Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein," often called the first science-fiction novel, Victor Frankenstein uses his scientific gifts to unlock the secret of instilling life, cobbling together a living creature from pieces of corpses.

In the last few years, and certainly since Shelley's time, science has in fact pushed back the borders between life and death. In the past, death was viewed as a single event, and a stopped heart or the cessation of breathing meant the individual was dead. But scientists now increasingly see it as a process. Scientists know that the body's cells can live on after the blood stops flowing, with some tissues lasting for days. Brain damage does not, as traditionally believed, occur as soon as blood stops flowing, but happens in stages. In fact, the process of cell death does not begin until after the traditional definition of bodily death occurs. The science of resuscitation has discovered that people can, in fact, be revived even hours after the heart has stopped.

The use of a technique called induced hypothermia has transformed some medical approaches to resuscitation. Putting "dead" individuals on ice reduces brain cells' need for oxygen, delaying cell death. As a result, supplying oxygen can be counterproductive. A flood of oxygen to a revived individual, ironically, brings on brain-cell death more quickly. Hypothermia-aided revival of the "dead" still doesn't reach Frankensteinian extremes, however, as cell damage will become too great for revival after some point.

In the time since the 1818 publication of Shelley's novel, the use of "dead" body parts has undergone a sea change in the field of transplantation. The first "modern" transplant — of a thyroid gland — took place in 1883. Organ transplants saw greater success in the early 20th century, when immunologists realized the reasons for tissue rejection. However, in the 1930s, the first attempted cadaver-derived transplantation, which was of a kidney, failed due to rejection. The powerful immunosuppressant cyclosporine, developed in 1970, ushered in a new era of transplantation, and body parts from deceased donors saved many lives. (Photo credit: Ben King - © 2013 - Lionsgate)

February: In "RoboCop," drones don badges

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When Paul Verhoeven's original RoboCop hit theaters in 1987, mechanized police forces were pure science fiction. But when this February's reboot of the RoboCop franchise arrived, automated machines with badges looked much less fantastical. As in the original movie, this year's RoboCop sees the hero cyborg Alex Murphy serving as a "human face" of the Detroit police force's army of fully robotic officers.

Though not nearly as advanced as ED-209, the terrifying drone in the movie, existing drones have taken on greater roles in police forces across the country, as well as in the U.S. military. In the past, many in the military dismissed drones — or pilotless vehicles — as ineffective toys. The technology gained credibility in 1982, after the Israeli army used aerial drones to help dismantle the Syrian air force. Over the years, advances in software, hardware and communications have transformed drones from expensive toys to vital pieces of technology, similar to what has happened with personal computers, said drone historian Richard Whittle. The biggest technological leap, he said, came with the introduction of the Predator drone in 2001, which for the first time permitted the military to kill an enemy remotely from across the world. Since then, drone technology and use has exploded, Whittle said. Military officials and experts foresee fleets of aerial, ground-based and seagoing drones heading into battle, frequently alongside human pilots and soldiers. The military now has 8,000 unmanned aircraft, of 14 different types.

And the technology has come to police forces. A 2012 federal ruling permitted their use by civilian and police forces, and the Department of Homeland Security has offered grants to help police forces buy the technology. Cops now use drones for surveillance and tracking criminals as they flee. Many police forces facing budget cutbacks see drones as a way to bolster forces. Of course, no police departments use the sort of armed Predator drones employed by the military, so a RoboCop reality of machine-gun-mounted robots is still a fiction. But, even without the armaments, police drones already have privacy advocates talking about problems of robotic surveillance in society. (Photo credit: © 2013 - Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures Inc. and Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. All Rights Reserved.)

March: "Divergent" looks at the tricky task of testing personality

In March's young-adult dystopia "Divergent," society slots young people into one of five factions based on an aptitude test. The groups specialize in a particular "virtue" and associated thinking style, submitting to their appropriate roles in society. "Abnegation," for example, is the selfless group that rules the government, while Dauntless ("the brave") serve as soldiers. The society runs into trouble with so-called "Divergents," who employ thinking styles of multiple groups.

In real life, some highly influential methods of aptitude testing tend to make this same mistake with most people — placing individuals into rigid categories that don't really fit. Thousands of HR departments and schools use the Myers-Briggs personality inventory to help predict the test taker's best career path. It slots people into the familiar categories of Thinking-vs.-Feeling, Introverted-vs.-Extroverted, Sensing-vs.-Intuition, and Judgment-vs.-Perception, and the $20-million industry of training and test administration has advocates across the country. The problem? It has virtually no scientific basis. Created by two women during World War Two, the test was derived from its authors' interpretation of the theories of psychologist Carl Jung (whose work is itself often called unscientific).

The psychological profession largely rejects the test, and statistical studies show the personality categories used by the test don't hold up to scrutiny. As organizational psychologist Adam Grant wrote, the test has no predictive power and gives inconsistent results. Put another way, as Joseph Stromberg wrote in Vox, Myers-Briggs has little more scientific validity than a BuzzFeed personality test. The major criticism of Myers-Briggs is that it simplistically labels people using binaries — either introverted or extroverted, for example. Real personality is more complicated, psychologists say, and people never fit that neatly into either-or traits. In fact, results for the same person can change drastically depending on the day that person takes the test.

"Divergent's" emphasis on people's thinking styles echoes another highly influential, but questionable psychological framework: Under Howard Gardener's "theory of multiple intelligences," people can excel in one or more of five types of intelligence, from verbal-linguistic to bodily-kinesthetic. However, despite the influence of this theory in school systems across the country, it has been discredited by neurologists and labeled "implausible" due to a lack of empirical evidence. Neurological and genetic research finds that the aptitudes Gardner identified actually overlap, and are not distinct types. (Photo Credit: Photo by Jaap Buitendijk - © 2013 Summit Entertainment, LLC. All rights reserved)

April: "Captain America" asks what is peak human performance?

In April, Marvel Comics' most star-spangled superhero returned to the screen to face a nemesis named "The Winter Soldier." Both characters are a certain type of superhero: not necessarily superpowered, but representing the peak of human physical potential. According to comics tradition, Captain America's "super solider serum" gave him the physical attributes of a peak human athlete, equaling or excelling Olympic athletes in virtually all events. But what would a "peak-human" Captain America mean in real life?

Physiological and mechanical constraints place upper limits on how strong the human body can get, says Todd Schroeder, a kinesiology professor at the University of Southern California. For example, historical records of weight-lifting contests show a plateauing of top lifts, so today's lifters are likely near the max, Schroeder said. Captain America, then, might heft a 600-lb. deadlift, like world record holder Richard Hawthorne. And speed records will also eventually plateau, according to Stanford biomechanics professor Mark Denny, who says the human limit for the 100-meter dash is 9.48 seconds — 0.10 seconds speedier than world-record holder Usain Bolt. In terms of endurance, humans have reached some incredible achievements, like Kilian Jornet scaling and descending the 8,000-foot-high Matterhorn in under 3 hours.

Clearly the human body can accomplish some amazing — and scientifically feasible — feats. But the idea of a superathlete competing at the top level in every category strains scientific credulity. That's because much of the record-breaking athletic achievements come from body specialization, sports writer David Epstein said in a TED talk this year. Today, people who achieve at the highest levels of an athletic field must have body shapes ideally suited to that sport. Michael Phelps, for instance, has a superlong torso and comparatively short legs, whereas marathoners need long, narrow legs and short torsos, Epstein said.

So Captain America could not, with a single body type, achieve both "Olympic-level" endurance and Olympic-level speed, to say nothing of Olympic-level swimming, gymnastics and weightlifting. Perhaps appropriately for a 1940s-era superhero, Captain America represents an old-fashioned perspective on athletics, in which coaches assumed the same basic body type was ideal for all sports, Epstein said. (Photo Credit: © 2013 - Marvel Studios)

May: "Godzilla" shows how to make a giant

Godzilla's been working out (and/or overeating). This May's "Godzilla" saw the beloved beast towering over 100 meters (a 30-story building) and carrying a staggering 164,000 tons of monster girth. Think you'll ever witness a monster like Godzilla? In real life, animals with gigantism can reach extreme sizes, but physics puts the brakes on fantasies of Godzilla-size beasts. In the phenomena known as "island gigantism," some isolated species have grown to gargantuan proportions, such as the Komodo dragon. Scientists have postulated that when a species is the first of its niche type to colonize an island, the abundant resources and opportunity to dominate competitors encourage gigantism. In "deep-sea gigantism," creatures like the "colossal squid" and Japanese spider crab can reach enormous sizes compared with their closest relatives. Scientists hypothesize that the slower pace of life and colder temperatures in the deep ocean may encourage gigantism.

Both phenomena seem appropriate to the Japan- and Hawaii-terrorizing Godzilla. But the obvious real-life inspirations for Godzilla are, of course, the dinosaurs. The sauropods, Earth's biggest-ever land animals, could reach 130 feet in length and weigh 110 tons. A few dino-traits explain how they so thoroughly outclassed today's large mammals. First, as German paleontologist Heinrich Mallison writes, dinosaurs had air-sac-filled bones, helping to alleviate the danger of overheating that comes with so much body mass. Big dinos also had flat-topped bones, unlike the rounded bones of mammals, meaning dino joints could pack on layer after layer of cartilage to support the beasts' excessive mass. Since they laid eggs, dinosaurs could also more easily produce more offspring at larger sizes — a problem for mammals, which give birth to live young. Finally, some scientists say the extensive ecosystems of dino-era supercontinents and a mostly warm climate encouraged larger size.

But the sauropods may also represent a theoretical upper limit for terrestrial animals. According to the square-cube law, as an animal grows, mass increases by unit cubed, while surface area (and thus, strength of bones) increases only by unit squared. Thus, a real-life Godzilla's organs would implode; his joints would collapse, and his body would overheat. (Photo Credit: Warner Bros. Picture - © 2014 Legendary Pictures Funding, LLC and Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.)

June: "Transformers" hints at real-life adaptable robots

Few people probably go to explosion-laden Michael Bay films for the science, but this June's "Transformers: Age of Extinction" also thrills with its vision of intelligent, transforming robots. The core "cool factor" of the transformer — its ability to dramatically alter its shape and function — is increasingly possible. Engineers are working on the concept of the modular, transforming robot, which could help alleviate the problem of limited-movement capabilities, and lead to better search-and-rescue drones and NASA probes.

Under a modular model, a robot would consist of a set of small, individual bots that could combine together in different conformations. Such a modular robot could, for example, link modules together in a snakelike shape to crawl through tunnels, then rearrange into a spider to scramble over rocky terrain. Even more impressively, lattice modular robots consist of modules that crawl over one another; simulations show they could assemble into shapes from teacups to animals.

But creating an Optimus-Prime-esque transformer presents a whole new set of obstacles. First, the size: A massive, walking robot of Prime's mass would require a lot of power, writes Tracy Wilson, noting that hydraulics would likely be necessary to permit all those massive moving parts. But such a system would entail the extra mass of water tanks or reservoirs. Programming such a robot to walk would prove even more difficult, Wilson writes. Deceptively complex, walking has proven unattainable by all except small robots who walk for short times, such as Honda's 119-lb. ASIMO, which can walk at 2 mph for 40 minutes.

In order to walk, a large robot would have to bypass rigid programming using artificial intelligence, and engineers continue to make progress in that realm, too. In June, a computer chat program named Eugene Goostman passed the famous Turing test, convincing questioners it was a human. Companies like Google continue to explore "deep learning" so that intelligent machines can answer questions, target advertising and drive cars. There's been enough progress in AI that both physicist Stephen Hawking and tech-entrepreneur Elon Musk recently warned of the dangers smart machines could pose to humanity. (Best to have some Autobots on the good side, then?) (Photo Credit: Industrial Light & - © 2014 Paramount Pictures. All Rights Reserved. HASBRO, TRANSFORMERS, and all related characters are trademarks of Hasbro.2)

July: "Planet of the Apes" echoes the intelligent apes already here

After a series of sequels, prequels and a soft reboot, the "Planet of the Apes" franchise reached eight movies with July's "Dawn of the Planet of the Apes." Clearly, the series' portrayal of chimps, gorillas and other great apes upgraded with human-level intelligence resonates among audiences. And with good reason: Beyond the physical kinship these animals share with humans (opposable thumbs, expressive eyes), the other great apes already resemble human smarts — without the need for a sci-fi intelligence serum.

In real life, several apes have learned language, sometimes to astonishing levels of sophistication. Koko the gorilla, for example, famously learned to express over 1,000 words in American Sign Language, and can respond to more than 2,000 spoken English words. The bonobo Kanzi, at the Great Ape Trust in Iowa, demonstrated that chimps can learn language as human children do — simply by being exposed to it. Scientists have also long observed chimps and orangutans using tools in the wild, beginning with Jane Goodall's experience with chimps employing twigs to fish ants out of holes. Researchers have even spotted a gorilla, often considered the dumbest of the great apes, using a stick to gauge the depth of a river.

Apes can think like humans, too: The orangutan Azy at Washington, D.C.'s, National Zoo demonstrated he could understand abstract symbols and had a "theory of mind" — that is, Azy understood that other individuals had minds like his own. In some cases, ape thinking even outclasses that of humans, with chimps besting human college students in tests of short-term memory.

In the action-packed new "Planet of the Apes" movie, of course, the apes do more than just demonstrate smarts; they also organize into militias to battle humans. Again, real-life, nonenhanced apes can also perform this seemingly distinctly human act. Goodall observed the first example of chimp warfare, in which the animals organize into groups to raid other chimp territory. And this September, a five-decade study showed that this type of warfare is innate to chimps, and not caused by human observation or encroachment. (Photo credit: © 2013 - Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation.)

August: "Guardians of the Galaxy" surprises with Groot's animal-like cousins

This year's biggest box-office hit, "Guardians of the Galaxy," was a space epic chock full of science-fiction elements and characters. But the biggest star may also have been the weirdest: a talking plant-creature named "Groot." The lumbering, sweet-natured but combat-ready Groot astonished both audience members and fellow on-screen characters by blending aspects of the plant and animal kingdoms.

But as weird as Groot appears, plant and animal organisms already have more in common than you might imagine. People tend to think of plants as inert because they don't (appear to) move, said Danny Chamovitz, director of the Manna Center for Plant Biosciences at Tel Aviv University and author of "What a Plant Knows" (Scientific American, 2012). In fact, much like Groot, plants have a rich sensory system and clearly communicate with one another, Chamovitz said. "The strong scientific evidence is that plants have every sense familiar in animals, except hearing."

Plants have a system analogous to the animal sense of smell, and are capable of recognizing chemicals using a molecular lock-and-key mechanism. Leafy organisms also have photoreceptors for responding to specific wavelengths of light — the plant version of vision. Senses have similar effects in plants and animals, too. A chemical, light or other bit of sensory information registers in the plant's sensory mechanisms, sending a signal through the plant body, which results in some sort of response. When a houseplant grows toward the light, for example, its body has responded to sensory information. Plants, too, can release chemical messengers both within their own bodies and into the air — affecting their leafy neighbors. For plants, this is communication, Chamovitz said.

The biggest difference between Groot and everyday plants is the speed of his movement, said Simon Gilroy, a professorof botany at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Plants simply can't produce enough energy for animal-style locomotion. But plants do move; they just do so by growing. Venus flytraps, for example, close their traps via rapidly dividing cell walls — essentially, undergoing speedy growth, Gilroy said. (Photo Credit: © 2014 - Marvel Studio)

September: "Maze Runner" reveals what happens when memory fails

Do you remember when the young-adult sci-fi film "Maze Runner" hit theaters this fall? If so, you're likely in better mental condition than the film's protagonist, who awakes in a speeding elevator, with no memory of his personal history. He doesn't even recall his own name — the name, Thomas, later returns along with some other memories. Thomas finds himself deposited into a dystopian maze, surrounded by other young people who also arrived with their memories scrubbed.

Though frequently a plot device of B-movie sci-fi and daytime soap operas, amnesia can and does occur in real life. Usually, however, amnesia accompanies some sort of brain injury that results in a set of symptoms in addition to memory loss, Jason Brandt, a professor of psychiatry and neurology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, told Live Science. The amnesia of the type Thomas suffers — isolated, and absent any brain injury or other symptoms — happens much more rarely. But when such an "amnestic syndrome" does happen, it's usually from some sort of emotional trauma, Brandt said, with the patient, at least subconsciously, hoping to avoid dealing with a troubling event.

Thomas' amnesia would likely be called "retrograde amnesia," meaning he lost biographical memories that occurred before an event. The film accurately portrays how, in such a case, the patient would still be able to function, remembering generally how to operate in the world, but without specific, personal memories. In "Maze Runner," however, Thomas' memory loss comes not from emotional trauma, but instead from manipulation by malevolent scientists. Neurological studies have taken some very small steps toward that kind of memory manipulation. An August MIT study in rats showed that it was possible to remove a bad memory (of a shock) and replace it with a good one. The extremely simple memory manipulation, however, involved only an association — the simplest type of memory, said UC-Irvine memory researcher Lawrence Patihis. Manipulation of complex biological memories is very far away, he said. (Photo credit:© 2014 - Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation.)

October: "Dracula Untold" wonders if vampires really exist

Dispensing with the original Bram Stoker version of the tale, this October's "Dracula Untold" focused on the purported historical inspiration for Stoker's vampire tale: Vlad "The Impaler" Tepes of Romania. The movie still goes in for the supernatural (Vlad gets his vampiric powers from a demon he meets in the woods), but does aim for a somewhat historical basis. The Vlad of history was a hero to his homeland of Romania, celebrated for leading it against the Turkish Empire. Only more Western perspectives record Vlad as a sadistic killer—"the Impaler."

Some scientists have tried to find a medical, as well as a historical, basis for the legends of vampires. In 1985, Canadian biochemist Dr. David Dolphin set forth porphyria as the source of both vampire and werewolf tales. Actually a set of conditions, porphyria results from problems in the production of heme, a molecule necessary for proper red-blood-cell function. The condition causes the buildup of porphyrin pigments, which cause severe sensitivity to light and, in some cases, physical disfigurement. It can, for example, result in the loss of noses, lips and gums, potentially exposing the teeth in a fanglike fashion. Adding up the sunlight sensitivity, exposed teeth, disfigurement and need for functioning red blood cells, Dolphin proposed a clinical basis for vampire legends. The capper: porphyria toxins can also cause sensitivity to a chemical found in garlic.

However, subsequent critics have shown that Dolphin's hypothesis misinterprets both vampire legends and the porphyria disease. Early vampire myths did not include light sensitivity — that was a later addition to vampire lore. And drinking blood has no effect on people with the disease, since the needed molecules in blood would not survive ingestion. The normal process of bodily decay may provide a simpler explanation for the myths. In superstitious societies that blamed misfortune on the recently deceased, digging up the corpse would present some troubling images: Sealed coffins would delay putrefaction, suggesting the corpse was still living. Meanwhile, internal release of gases in the corpse's intestines would cause bloating, signaling that the body had engorged itself (on blood?). Anthropological studies in New England have, in fact, demonstrated interference with buried corpses coinciding with vampire hysteria. (Photo Credit: Photo by Jasin Boland - © 2014 - Universal Pictures)

November: "Interstellar" nails it when it comes to black holes

By far the most scientific of sci-fi movies this year, November's "Interstellar" pleased no less a critic (and science stickler) than noted astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson. After famously Twitter-panning the scientific accuracy of last year's "Gravity" (complaining, for example, that astronaut Sandra Bullock's hair didn't float in zero gravity), Tyson mostly praised the science of Christopher Nolan's space epic. The film is the first to give an accurate portrayal of how both a wormhole and a black hole would look and behave, according to current physics theories. The movie shows "Einstein's Relativity of Time" and "Curvature of Space as no other feature film has shown," Tyson tweeted in November. The filmmakers took great care to accurately represent the physics, employing another noted physicist, Kip Thorne, to advise on and produce the movie. Thorne worked closely with the visual effects team, supplying the real physics equations describing the phenomena the filmmakers wanted to model.

That attention to detail resulted in a portrayal of the wormhole's entrance as a shimmering sphere, consistent with theories about the objects. Predicted by Einstein's theory of relativity, though never yet observed, wormholes are proposed space-time tunnels between distant points in the universe. "Interstellar's" astronauts use such a wormhole to travel to far-away planets. In doing so, they encounter worlds orbiting a black hole. And again, the effects team got the physics right — and spectacularly so, Tyson told NBC News. The film portrays the "time dilation," or slowing of time effect that is created by the massive gravitational pull of a black hole on nearby space-time.

Other weird, but accurate, effects also appear, such as the way a black hole would warp the light of objects behind it via "gravitational lensing." On one of the planets, the astronauts encounter mountainous waves, an accurate portrayal of the tidal effects of a black hole. A few quibbles aside — neither a planet nor astronauts could get as close as they do to the black hole portrayed in the movie, for example — "Interstellar" does a stellar job on the science. So good, in fact, that Thorne and the effects team plan to publish two peer-reviewed science articles based on their work. (Photo credit: Paramount Pictures 2014)

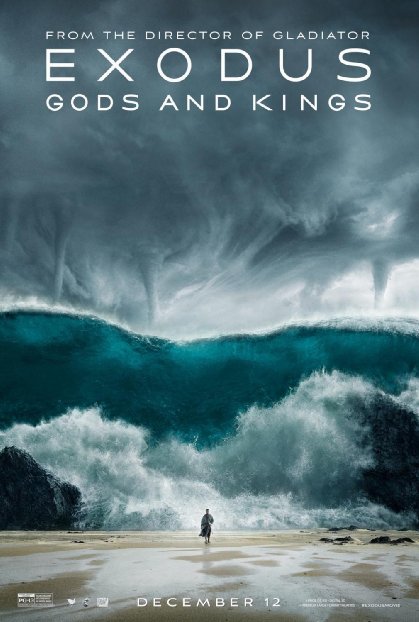

December: "Exodus" shows how science parts the sea

Ridley Scott's film "Exodus: Gods and Kings" is not sci-fi, of course; it's a Biblical epic. But the Christian Bible's blending of history and religious tales has invited some experts to look for scientific explanations of the work's supernatural elements — just as one might in a sci-fi movie. In this movie, Scott's portrayal of perhaps the greatest of Biblical miracles, Moses' parting of the sea, aims to take a more naturalistic look at the event, thus inviting even more scientific scrutiny.

Instead of two huge walls of water as in Cecil B. DeMille's 1923 film "Ten Commandments," Scott's new film depicts a tsunami. This led former NOAA scientist Bruce Parkerto speculate on a different explanation: tides. In the area around the Red Sea where Moses supposedly crossed, tides are predictable, and can leave the seabed dry. High tide can also rush back in swiftly. In fact, Parker writes, Napoleon and a few soldiers were once crossing such a seabed in the Red Sea, and nearly drowned when the high tide returned. The Bible says that Moses, Parker writes, grew up in the wilderness around the crossing, and so may have known the timing of the tides. Pharaoh and his advisers, used to the nearly tideless Nile, would have been caught unawares, Parker wrote.

In another hypothesis by software engineer Carl Drews, a weather phenomenon called a "wind letdown" could have sloshed a mass of water to one side of the sea or lake that Moses crossed, only to bring it crashing back in later. Drews' hypothesis, written for his master's thesis in atmospheric and ocean sciences and published in 2010 in the PLOS One journal, depends on a slight change in location for Moses' crossing. As some scholars have noted, "Red Sea" is a mistranslation of "Sea of Reeds," and Drews identifies this body of water as the shallow, brackish Lake of Tanis. Such a body would be beset by reeds, Drews said — and also vulnerable to the type of wind letdown his paper describes.

Follow Michael Dhar @michaeldhar. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Michael Dhar is a science editor and writer based in Chicago. He has an MS in bioinformatics from NYU Tandon School of Engineering, an MA in English literature from Columbia University and a BA in English from the University of Iowa. He has written about health and science for Live Science, Scientific American, Space.com, The Fix, Earth.com and others and has edited for the American Medical Association and other organizations.