Our Hunt for the World's Deepest Fish (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. The publication contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

It was our 14th expedition to the trenches of the Pacific Ocean, where depths can exceed 10,000m. And it was due to be our last for the foreseeable future.

We had been aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s (SOI) vessel RV Falkor for 30 days. It was almost over. Then, it turned out to be “the big one”.

For this was the expedition in which my colleagues and I discovered a snailfish living some eight kilometres below the waves, deeper than any fish we know of. My colleagues from the University of Hawaii even recovered some in their traps.

In the past six years we have made many discoveries in the depths, such as the missing order of Decapoda (shrimps) that were long thought absent from the trenches but are actually rather conspicuous.

In the Kermadec Trench off New Zealand we found the “supergiant” amphipod, a crustacean 20 times larger than its shallow-sea relatives. We also filmed large numbers of tadpole-like snailfish in multiple trenches, and as deep as 7700m in the Japan Trench.

Snailfish surprise

Based on these observations we predicted that when exploring the Mariana Trench – the world’s deepest – we would find the the Mariana’s own personal snailfish, probably living between 6500m and around 7500m, with more being found at the deeper end of that range.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

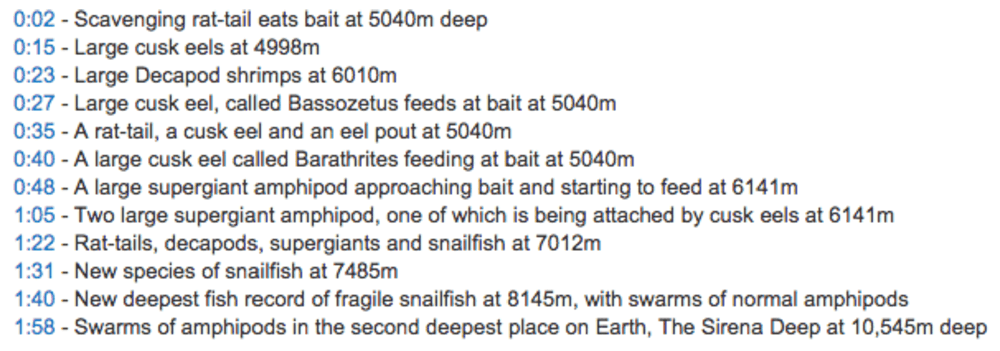

Exploring the Mariana Trench. The record-breaking fish appears at 1:45

We also predicted that we would see the decapods and supergiants in the upper depths of the trench, and right enough there they were.

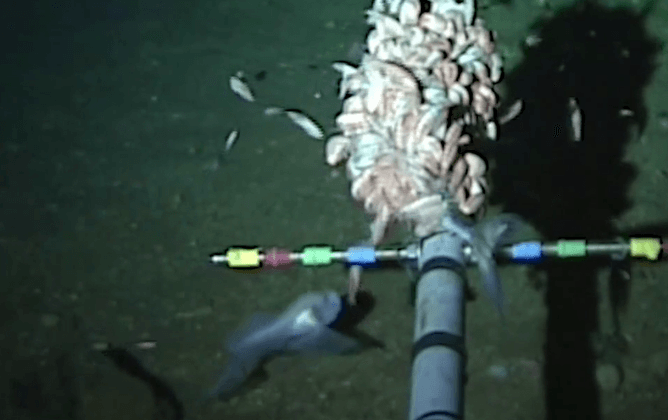

A device used to gather samples of ocean floor had an inspection camera on it to monitor the equipment. One night after a dive to 7900m when watching the footage coming back in, a strange ethereal little fish swam past. That got our eyebrows raised. It looked like a snailfish, but was extremely fragile (even for a snailfish) and had a very distinctive appearance.

This prompted a case of “game on”, to find it again, and sure enough we did. The deepest we found it was at 8145m, nearly 500m deeper than our personal record from the Japan Trench.

This of course means that our predictions were slightly wrong, but also makes it very exciting: there are still fish, and perhaps other things, down there to discover and this is what drives us to do more. Our work at the deepest place on Earth is not done yet.

Why we need to keep exploring

As much as we are excited about finds such as these, we are typically chased up by people who ask “why do we bother?”, and add rather deflating comments such as “what benefit does this have to society?”

In response I explain that such exploration benefits responsible stewardship of the oceans. In the long term, conservation and maintenance of the our seas relies on us really understanding the ocean – that is, the ocean in its entirety from the surface to what lies beneath the deepest seafloor. The anthropocentric opinion of “out of sight, out of mind” simply doesn’t cut it, and is sadly still common place.

The deep ocean is far deeper than a person can dive to or fish from, but that doesn’t mean that the things down there are of no consequence to society. We must not, however, confuse curiosity-driven exploration with the search for entertainment or stockpiling consumables.

We know that the deep sea is not exempt from a changing climate or man-made disturbances such as plastic pollution. The depths are intrinsically linked to processes in the upper ocean that we humans are continually meddling with.

Changes that happen in the upper ocean will have an effect on the largest habitat on Earth, yet people question why we study the deep sea. We say, how can we conserve the largest habitat on Earth if we know nothing about it? In the quest to understand the entire ocean, people have to study the shallow bits, the deepest bits and everything in-between.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.