The microbes that live in and on humans may have evolved to preferentially take down the elderly in the population, a new computer model suggests.

That, in turn, could have allowed children a greater share of food and resources, thereby enabling an extended childhood. Such a microbial bias may also have kept the first human populations more stable and resilient to upheavals, the findings suggest.

"If you go back 30,000 to 40,000 years ago, there were only 30,000 to 40,000 people in the world and they were scattered over Africa, Europe, and parts of Asia," study co-author Glenn Webb, a mathematician at Vanderbilt University, said in a statement. "Are we lucky just to be here? Or did we survive because our ancestors were robust enough to handle all the environmental changes and natural disasters they encountered?"

The new findings suggest that humans survived because as a whole, ancestral human populations were tough enough to survive the environment, he said.

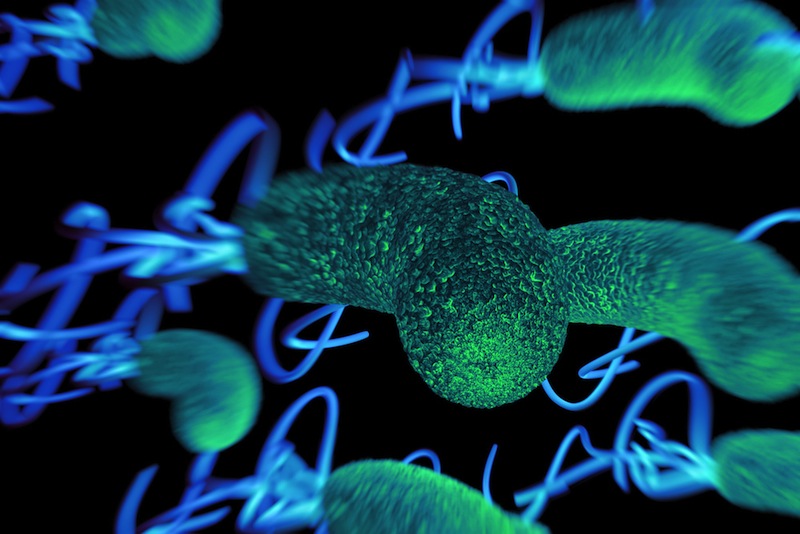

Microbiome

By some measures, the human body is more bacteria than human. The number of bacteria cells in the body outnumbers human cells by about 10 to 1. In recent years, scientists have found that this microbiome has far-reaching effects, modulating weight gain, mood and cognitive function. [Body Bugs: 5 Surprising Facts About the Microbiome]

Dr. Martin Blaser, a microbiologist at New York University's Langone Medical Center, began wondering about the effect of bacteria on age structure. He noticed that the stomach bacteria Helicobacter pylori, could live symbiotically in people's guts for decades, without causing them any harm, but it could also cause stomach ulcers and stomach cancer — a risk that grows with age.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I began thinking that a real symbiont is an organism that keeps you alive when you are young and kills you when you are old. That’s not particularly good for you, but it’s good for the species," Blaser said.

It's possible that these bacteria helped reduce the number of elderly people in a population, thereby allowing the children to get a greater share of food and resources, the researchers said. In other words, the bacteria enable the extraordinarily long childhood that humans experience relative to other animals.

Modeling bacteria

To look at the microbiome's effects on people as they age, Blaser and Webb created a mathematical model to simulate an ancient hunter-gatherer population.

In their model, they assumed that the people had the same maximum life span that modern humans do, of about 120 years. (Though early hunter-gatherers had a lower life expectancy than humans that was due to other factors, such as childhood diseases, physical injuries that couldn't be healed and microbial diseases that can now be treated with antibiotics.)

The model grouped people into one of three groups: youngsters, people of reproductive age, and those past their reproductive years. Then the researchers watched how the population changed based on different fertility and mortality rates.

To capture the effects of "bacteria," they tweaked the mortality factors associated with different types of microbes.

For instance, in one version of their model, they increased the prevalence of Shigella, a type of bacteria that causes food poisoning, and can kill young children. That led the population to crash.

In another model, they added in the effects of bacteria often found in the stomach called Helicobacter pylori, which increase with age. The team found that adding H. pylori's effects created a stable population, where more of the oldest people died off. That, in turn, allowed the juveniles to get a greater share of the food and resources, and allowed for overall greater population growth and stability. By contrast, populations without H. pylori had a greater share of older people and gradually declined.

Their calculation suggests that bacteria may have evolved to target the older people in the population.

This would not only benefit the human population, but the microbial colonizers as well, because the microbes depend on having a steady supply of hosts to infect, the researchers said.

The findings were published Dec. 16 in the journal mBio.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.