Stayin' Alive: Disco Clam Has a Flashy Defense Strategy

Many predators lurk in the tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific Ocean, but the so-called disco clam has a flashy defense mechanism — a spectacular light show — to scare away potential threats.

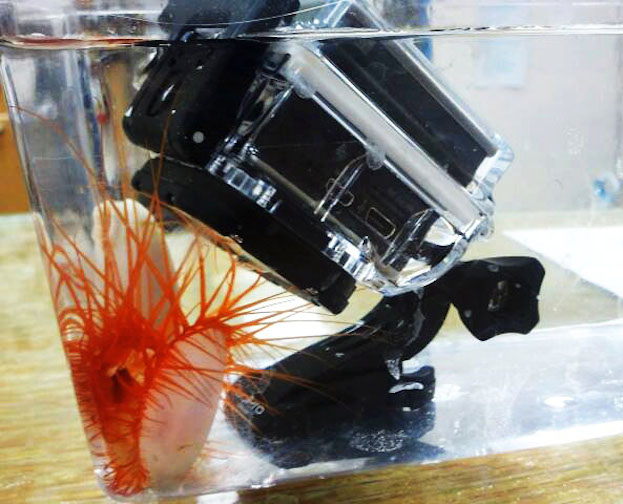

These small, 2.8-inch-long (7 centimeters) clams have tiny shiny silica spheres in their lips that can reflect light and put on a glimmering underwater display. By studying the animal's flashes, researchers have determined that the disco clam (Ctenoides ales) may use this luminous ability to intimidate predators and attract light-loving prey, said the study's lead researcher Lindsey Dougherty, a doctoral candidate of marine biology at the University of California, Berkeley.

"When most people imagine clams, they imagine the things that make clam chowder," Dougherty said. "These clams are very different. They're reef-dwelling, they have bright-red tentacles, they have gills that stick out, they live in little crevasses [and] they are the only species of clam that flashes." [See video of a mantis shrimp trying to attack a disco clam]

The researchers placed the disco clams in an aquarium, and used a floating Styrofoam lid to mimic a looming predator, "which turned [out] to be very scary" for the clams, Dougherty told Live Science.

The clams' flash rate jumped from 1.5 times a second to 2.5 flashes a second when the lid was nearby, the researchers found. Disco clams may also use sulfuric acid to keep predators at bay, the scientists said.

Dougherty used calcium chloride, which makes a white precipitate in the presence of sulfuric acid. "I found about twice as much precipitate in the disturbed clam than in the calm clam that I just left alone," she said.

More tests are needed to verify that disco clams secrete sulfuric acid when threatened, but the defense is a common one among other marine creatures, including some snails and other clams.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The sulfuric acid could be a critical part of the clams' defense strategy. "If you're flashing and saying, 'I'm distasteful; don't eat me,' that's one thing, but you have to sort of back it up," with something like sulfuric acid, Dougherty said.

The one-two punch seemed to work wonders on a peacock mantis shrimp. At first, the mantis shrimp struggled to open the disco clam. But then, it suddenly recoiled and became went into a catatonic state, or a state of stupor, leaving the clam alone.

It usually takes a mantis shrimp about 45 minutes to crack open a clamshell, so "that is very strange behavior [for the mantis shrimp]," Dougherty said. "They're very aggressive critters, and to have a clam open and flashing, and the mantis shrimp not attacking, is very weird." [In Photos: Spooky Deep-Sea Creatures]

It's likely that the clam used sulfuric acid, or another irritating agent, to protect itself, Dougherty said.

Preliminary tests also showed that disco clams flash more times a second when prey, such as plankton, are nearby. But it's difficult to test the clam's eating habits in an artificial environment, so Dougherty and her colleagues plan to travel to Indonesia this year to study the disco clams in their natural ecosystem.

Another test found that, although the clams have about 40 tiny eyes, their vision likely isn't good enough to detect the flashing of other disco clams for mating purposes. Researchers think disco clams are born as males and then change into females as they age, but it's unlikely that the clams use their flashing light show to attract mates, she said.

"We did not find much chemical or visual attraction to one another, and research into their eyes suggests they may not be able to perceive the flashing in one another," Dougherty said.

The researchers also plan to study the origin of the tiny, reflective silica spheres in the disco clam's lips, and whether they come from ingested plankton, siliceous sponges or sand.

Dougherty's team may be the only group currently researching the disco clam, said Jeanne Serb, an associate professor of evolutionary biology at Iowa State University who was not involved with the study. Many people in the pet trade knew of the clam's light show, but "nobody knew why they did it or how they did this, and that's why Lindsey [Dougherty]'s work is so important," Serb said.

Many people have dismissed mollusks as "relatively simplistic" because they don't have heads, but research shows that they have complex behaviors and a unique set of genes, Serb said. For instance, the oyster genome has 28,027 genes, about a third of which are unique to the oyster, according to a 2012 study published in the journal Nature. Likewise, Serb found that a large portion of the DNA coding for the sea scallop's vision are unique to mollusks.

"What Lindsey's work is going to help with is, getting some focus on this large group of organisms that actually have lots of really strange and unusual functions and interesting traits," Serb said. "And I think this gets back to what is going on with their DNA."

The unpublished research was presented today (Jan. 4) at the 2015 annual conference of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology in West Palm Beach, Florida.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.