How Greenland Got Its Glaciers

Greenland is famous for its massive glaciers, but the region was relatively free of ice until about 2.7 million years ago, according to a new study. Before then, the Northern Hemisphere had been mostly ice-free for more than 500 million years, the researchers said.

The Greenland ice sheet began building after plate tectonics and the Earth's shifting tilt reshaped the region, the researchers found. The team narrowed the cause down to three factors: plate tectonics that lifted the region, creating soaring snow-capped mountain peaks; a northward drift from plate tectonics; and a shift in the Earth's axis that caused Greenland to move farther north, away from the sun's warmth.

"Our work was motivated by the question of why extensive glaciations of Greenland started only during the past few million years," the researchers wrote in the study. [Images: Greenland's Gorgeous Glaciers]

About 60 million years ago, a plume from the Earth's mantle, several layers below the planet's upper crust, thinned out part of Greenland's lithosphere above it.

In some parts of Greenland, the lithosphere can be about 124 miles to 186 miles (200 to 300 kilometers) thick. But because of the plume, the lithosphere in East Greenland is often thinner than 62 miles (100 km), making it easy for rising hot rocks in the mantle to cause uplift.

About 5 million years ago, hot rocks underneath Iceland rose from Earth's mantle, and flowed northward toward East Greenland. With an already-thin lithosphere, this underground activity easily bolstered Iceland's mountains, causing them to reach more than 1.9 miles (3 km) above sea level.

In West Greenland, where the lithosphere is thicker, the mountains reach less than 1.2 miles (2 km) above sea level, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the scientists applied the underground activity from Iceland to a computer model, they saw how it acted over time.

"These hot rocks flow northward beneath the lithosphere, that is, towards eastern Greenland," the study's lead researcher, Bernhard Steinberger, of the German Research Centre for Geosciences GFZ, said in a statement. "Because the upwelling beneath Iceland — the Iceland plume — sometimes gets stronger and sometimes weaker, uplift and subsidence [sinking] can be explained."

Moreover, the researchers found clues in the eastern part of the country, where glaciation first began. Dating showed that rock samples from the tops of mountains in East Greenland were uplifted within the past 10 million years, when the hot rocks would have been pushing up the mountains.

Moving northward

But major glaciation in Greenland didn't start because of the mountain's uplift. Other factors were at play, the researchers found. Before 60 million years ago, Greenland was located at lower, and warmer, latitudes, the scientists said.

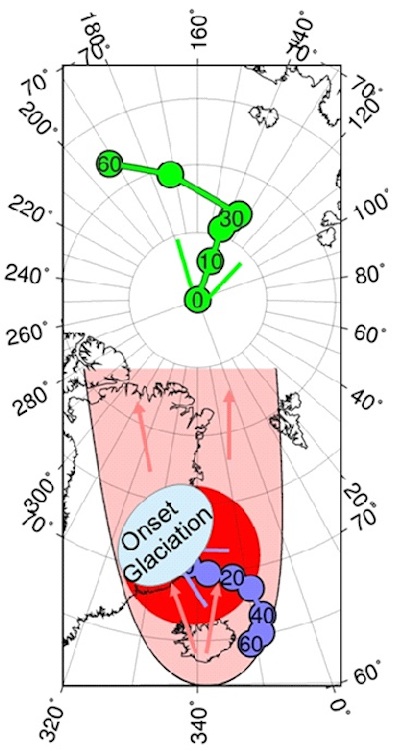

Plate tectonic reconstruction shows that over the past 60 million years, Greenland has moved about 497 miles (800 km) to the northwest over the mantle. This is equivalent to Greenland shifting 6 degrees northward on the globe, the researchers said.

The northerly move was magnified by "true polar wander," when the Earth's outermost layers naturally tilt and change location.

"Our computations show that the Earth axis shifted about 12 degrees towards Greenland during the last 60 million years" Steinberger said.

Between the tectonic plate movement and true polar wander, Greenland moved about 18 degrees to the north over the past 60 million years, the researchers found. Greenland's colder location, combined with its new, high mountains in the east, created opportune conditions for glacier formation, the researchers said.

But it's unclear how much longer Greenland will have enormous glaciers. Rising temperatures and sea levelsmay be contributing to glacier melt, according to a 2014 study published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

The new findings were published online Jan. 4 in the journal Terra Nova.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.