How to Recreate a Sloppy Ancient Greek Drinking Game

NEW ORLEANS — More than 2,000 years before the invention of beer pong, the ancient Greeks had a game called kottabos to pass the time at their drinking parties.

At Greek symposia, elite men, young and old, reclined on cushioned couches that lined the walls of the andron, the men's quarters of a household. They had lively conversations and recited poetry. They were entertained by dancers, flute girls and courtesans. They got drunk on wine, and in the name of competition, they hurled their dregs at a target in the center of the room to win prizes like eggs, pastries and sexual favors. Slaves cleaned up the mess.

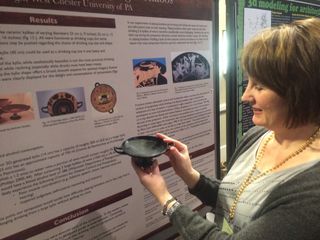

"Trying to describe this ancient Greek drinking game, kottabos, to my students was always a little bit difficult because we do have these illustrations of it, but they only show one part of the game — where individuals are about to flick some dregs at a target," said Heather Sharpe, an associate professor of art history at West Chester University of Pennsylvania. [11 Interesting Facts About Hangovers]

"I thought it would be really great if we could actually try to do it ourselves," said Sharpe.

So, with a 3D-printed drinking cup, some diluted grape juice and a handful of willing students, Sharpe did just that. She found out that it wasn't impossible to get the hang of kottabos, but the game did require a skilled overhand toss. She presented her findings this past weekend (Jan. 8 to 11) here at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Raise your glass

Ancient texts and works of art indicate that there were two ways to play kottabos. In one variation, the goal was to knock down a disc that was carefully balanced atop a tall metal stand in the middle of the room. In the other variation, there was no metal stand; rather, the goal was to sink small dishes floating in a larger bowl of water. In both versions, participants attempted to hit their target with the leftover wine at the bottom of their kylix, the ancient equivalent of a Solo cup.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The red-and-black kylixes had two looped handles and a shallow but wide body — a shape that perhaps was not the most practical for drinking but lent itself to playful decoration.

Big eyes were sometimes painted on the underside on kylixes so that the drinker would look like he was wearing a mask when he took a hefty sip. And the relatively flat, circular inside of the cup, called the tondo, often carried droll or risqué pictures that would be slowly revealed as the wine disappeared. The tondo of one kylix at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston bears the image of a man wiping his bottom. Another drinking cup at the same museum shows a man penetrating a woman from behind with the caption "Hold still."

Other paintings on kylixes were quite self-referential, with scenes of revelers playing kottabos. Based on those ancient illustrations, Sharpe had assumed that to play the game, you would swirl the dregs in the kylix and flick them at the target, almost as if you were doing a forehand throw with a Frisbee. But her experiment showed that that was not the most winning technique. [Coolest Archaeological Discoveries of 2014]

Re-enacting a symposium

Sharpe collaborated with Andrew Snyder, a ceramics professor at West Chester University. He initially made three replica kylixes out of clay, but Sharpe was worried about breaking them during the game. Snyder had just acquired a 3D printer (a MakerBot Replicator 2), so they made a lighter, more durable, plastic kylix at a slightly smaller scale.

The team made mock-up kottabos targets to play both variations of the game. For their andron, Sharpe and her colleagues used one of the art department's drawing rooms (which had a linoleum floor for easy cleanup), and they grabbed a couple padded benches to serve as their couches. Instead of wine, they used watered-down grape juice.

To achieve the best results in kottabos, the participants had to loop a finger through one handle of the kylix and toss the juice overhand, as if they were pitching a baseball. Sharpe said that playing the game proved to be challenging, but she was amazed that some of her students started to hit the target within 10 to 15 minutes.

"It took a fair amount of control to actually direct the wine dregs, and interestingly enough, some of the women were the first to get it," Sharpe told Live Science. "In some respects, they relied a little bit more on finesse, whereas some of the guys were trying to throw it too hard."

Elite Greek women wouldn't have taken part in symposia, but there are some indications that the courtesans, called hetairai, would have played kottabos with the men.

"Another thing we quickly realized is, it must have gotten pretty messy," Sharpe said. "By the end of our experiment we had diluted grape juice all over the floor. In a typical symposium setting, in an andron, you would have had couches arranged on almost all four sides of the room, and if you missed the target, you were likely to splatter your fellow symposiast across the way. You'd imagine that, by the end of the symposium, you'd be drenched in wine, and your fellow symposiasts would be drenched in wine, too."

Sharpe would eventually like to attempt to play kottabos with real wine, to fully understand how the game would devolve as the participants got tipsy.

"It would be fun to actually experiment with wine drinking," Sharpe said. "Of course, this was a university event, so we couldn't exactly do it on campus. But really, to get the full experiment, it would be interesting to try it after having a kylix of wine, or after having two kylixes of wine."

Editor's note: This article was updated at 2:30 p.m. ET on Thursday to correct Heather Sharpe's title. She is an associate professor, not an assistant professor.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular