Ancient Knife-Toothed Reptile Is Crocodile Cousin

The fossil of a prehistoric 9-foot-long (2.7 meters) carnivorous reptile that had sharp, serrated teeth is helping researchers fill out the early branches of the reptile family tree, according to a new study.

It's unclear where the reptile, Nundasuchus songeaensis, falls on the evolutionary tree, said Sterling Nesbitt, an assistant professor of geology at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

But the new findings show that “it is either the closest relative of the common ancestor of birds and crocodylians, or it is more closely related to crocodylians than to birds, most appropriately called "a crocodylian cousin," Nesbitt told Live Science.

In fact, the 245-million to 240-million-year-old Middle Triassic fossil has features of both birds and crocodylians, the researchers reported in a new paper on the fossil.

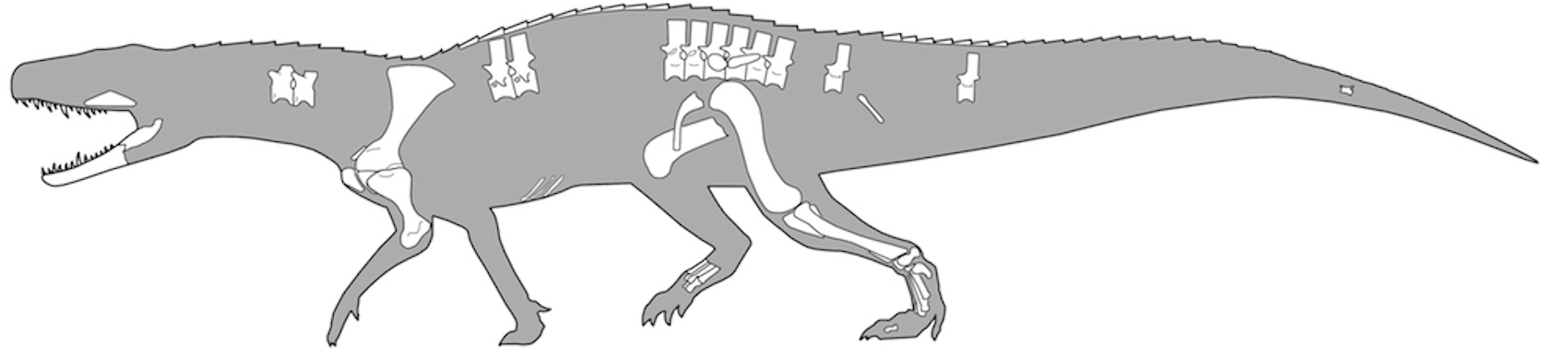

"The reptile itself was heavy bodied, with limbs under its body like a dinosaur or bird, but with bony plates on its back like a crocodilian," Nesbitt said in a statement.

Nesbitt discovered the fossil in Tanzania in 2007, and has now spent more than 1,000 hours with his colleagues uncovering, assembling and cleaning the fossil, combining thousands of pieces into a partial skeleton and part of a skull. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

The researchers named the new species Nundasuchus songeaensis, a name that includes a mix of Swahili and Greek. "Nunda" means predator in Swahili, and "suchus" is a Greek word that refers to the Greek word for crocodile.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The 'songeaensis' comes from the town, Songea, near where we found the bones" in southwestern Tanzania, Nesbitt said.

The team had hoped to find prehistoric relatives of modern-day birds and crocodiles, but discovering the fossil turned into a "eureka moment," Nesbitt said.

"There's such a huge gap in our understanding around the time when the common ancestor of birds and crocodilians was alive — there isn't a lot out there in the fossil record from that part of the reptile family tree," Nesbitt said. "This helps us fill in some gaps in the reptile family tree, but we're still studying it [the fossil] and figuring out the implications."

The researchers announced their findings yesterday (Jan. 20) in a statement. The research was published online on Nov. 4, 2014, in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.