Medieval Skulls Reveal Long-Term Risk of Brain Injuries

Skull fractures can lead to an early death, even if the victims initially survived the injuries, according to a new study that looked at skulls from three Danish cemeteries with funeral plots dating from the 12th to the 17th centuries.

This is the first time that researchers have used historical skulls to estimate the risk of early death among men who survived skull fractures, experts said. The study showed that these men were 6.2 times more likely to die an early death compared with men living during that time without skull fractures. Today, the risk of dying after getting a traumatic brain injury is about half that, likely because of improvements in modern medicine and social support, according to the researchers.

"Their treatment then would have been pretty much go home, lie down and hope for the best," said study researcher George Milner, a professor of anthropology at Pennsylvania State University. "There was very little that could be done at that time." [Inside the Brain: A Photo Journey Through Time]

Often, epidemiology — the study of disease incidence and prevalence among large populations — is confined to living samples. But the researchers suggest that skull fractures, much like high blood pressure or cholesterol in present-day patients, can be used in historic samples as markers for an increased risk of getting sick or dying.

"What we want to do is to be able to obtain figures or statistics that are comparable to those of today to give us a long-term perspective of pathological conditions of various sorts," Milner said.

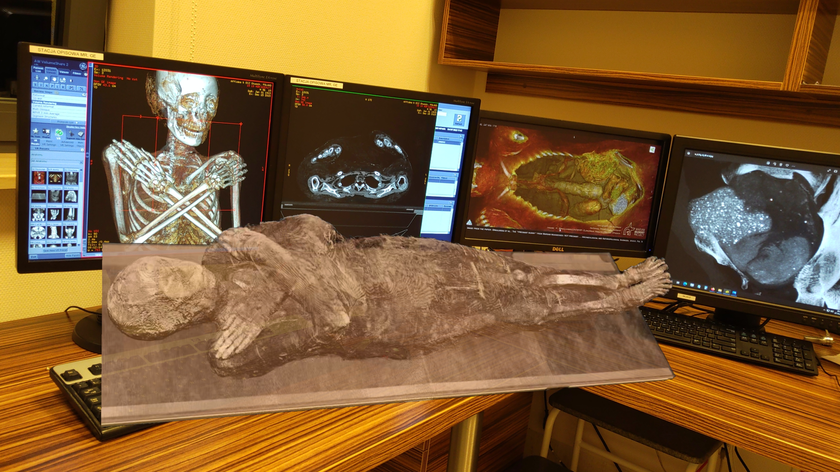

The researchers examined skeletons that were exhumed to make room for new building developments in Denmark. In all, the scientists found 236 skulls from men, including 21 individuals who had healed skull fractures.

Too few women had skull fractures, so they were not included in the analysis. The researchers also excluded men who appeared to have died immediately from their skull injuries, based on jagged and sharp fractures seen on the skulls. Healed fractures tend to have rounded edges from remodeled bone, Milner said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The vast majority only had one blow" to the head, Milner said. But two skulls had two injuries apiece, including a man with an injury on both sides of his head, and another man with separate injuries on the front and side of his skull.

It's likely that the fractures happened during violence or fighting between people or from work accidents, the researchers said. But it's unclear what ultimately killed the men.

One speculation is that these skull fractures were accompanied by traumatic brain injuries, which could have affected the men's longevity. But it's also possible the fractures and reduced longevity were caused by the same lifestyle traits among the men.

"Was it a lifestyle that caused the trauma that led to early death?" said Jane Buikstra, a professor of bioarchaeology at Arizona State University, who was not involved with the study. Or did the trauma lead "to a biological disability that may have predisposed early death?"

For instance, an aggressive man might get into fights and eventually die because of his violent lifestyle. Or, he might have sustained a brain injury from a skull fracture that put him at risk for dying of some other cause.

"There are a lot of studies that describe violence in the past," Buikstra said. "What this does that’s novel and important is that it looks at the degree to which the past people, who, though they survived the trauma, died earlier than individuals who were not affected by trauma."

The study was published Monday (Jan. 26) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.