Lava Bomb Fossils Hold Clues to Islands' Fiery Origin

Tiny fossils resurrected from a watery grave and shot to the ocean's surface in steaming lava bombs could help unravel the ancestry of the Canary Islands volcanic chain, according to a new study.

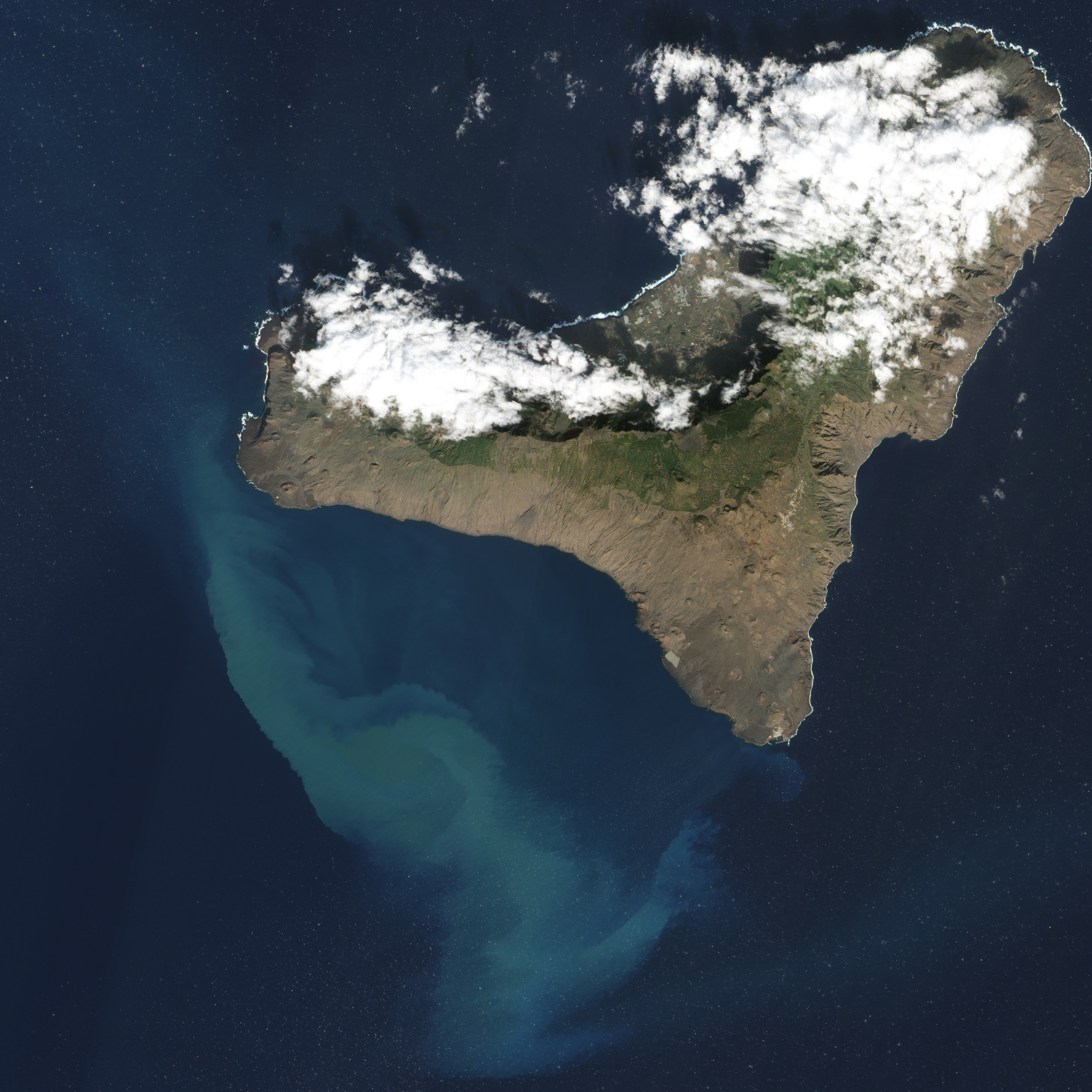

The Canary Islands, located offshore of northwestern Africa, are a long chain of volcanic islands similar to the Hawaiian Islands in the Pacific Ocean. However, in a mirror image of the Hawaiian chain, these Atlantic volcanoes grow younger from west to east, with the most recent eruptions bubbling up from El Hierro volcano in 2011.

Many scientists think that such strings of fiery volcanoes — such as the Canary Islands and the Hawaiian Islands — are evidence that the Earth's mantle contains plumes of hot rock that pool and remain stationary while the plates of the Earth's crust move over them. As tectonic plates trundle over the plumes, the heat generates magma that feeds volcanic eruptions. [Amazing Images: Volcanoes from Space]

Now, a new study favors a mantle plume origin for the Canary Islands.

"In the plume model, the islands mature as they move away from the source," said Valentin Troll, a volcanologist at Uppsala University in Sweden. And the Canary Islands do line up from youngest to oldest, like the Von Trapp family singers in "The Sound of Music." "We can see the juvenile, the adult and the [elderly] stage. I find it very striking that they all seem to go through a life cycle of similar stages," Troll said.

However, other researchers think there's a simpler explanation for what fuels the Canary Island volcanoes, which also line up with fractures and cracks in the seafloor. These fractures could let magma punch through the crust, which could contradict the idea that there must be a mantle plume below this part of the crust.

In the Canary Islands, there is evidence supporting both ideas, leading to an active debate over the islands' origins.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For instance, a 2013 study of lava rocks that were dredged up from the submerged seamounts (small, underwater volcanoes) surrounding the islands supports this alternative. The dredging dug up rocks that represented a grab bag of ages, rather a linear progression from west to east. For instance, rocks near El Hierro volcano were about 133 million years old, making them younger than rocks found both farther westward and farther eastward.

"The rocks turned out to be very much older than we expected," said Troll, who was not involved in the 2013 study. "Since that year, the entire question [of the islands' origin] has been entirely open."

Surprise inside

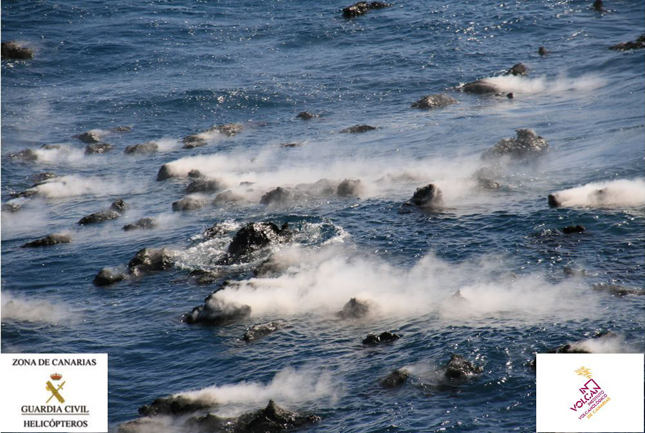

When El Hierro erupted in 2011, volcanologists who flocked to the eruption (including Troll) witnessed a strange and rarely seen phenomenon: Steaming, boulder-size blobs of hot lava resembling lava bombs rose to the ocean surface and then floated for miles, eventually piling up on beaches or sinking back down to the seafloor. These rocks are now called restingolites, for La Restinga, the village closest to the eruption. [Gallery: Eerie Rocks From El Hierro Volcano]

Anyone who cracked open a restingolite rock found a startling surprise: Inside the brown lava shell was cream-colored cooked carbonate, the remnants of marine rock picked up by magma before erupting. The restingolites resembled mint-patty candies mangled by the summer sun. Even better for geoscientists, there were fossils in the cores of some restingolites.

"It's exciting and unusual and a strange phenomenon to get fossils coming out of a volcano," Troll said. "But once you actually accept that sediments were picked up by rising magma, you realize that with these rocks, we can actually look under the volcano, which is not possible in any other way."

The scientists now think that marine sediments underlie El Hierro. Magma tunneling upward through the volcano picked up the carbonate rocks on its journey to the surface. The fossils are microscopic, single-celled marine creatures called coccolithophores, a type of phytoplankton that floats in the upper ocean. Their shells fall to the seafloor after the creatures die.

Like the rocks dredged up offshore El Hierro, the fossils range widely in age, from 100 million to 2.5 million years old, the researchers reported in a study published Jan. 22 in the journal Scientific Reports and led by Kirsten Zaczek, a graduate student working with Troll.

But the youngest fossils place new age limits on when El Hierro volcano formed, according to the study. The researchers think the 2.5-million-year-old fossils were present on the seafloor before the volcano began to grow. And the marine sediments offer a new way to explain the juxtaposition of dinosaur-age volcanic rocks next to a very young volcano. Troll thinks the marine rocks blanket an ancient volcanic province that formed more than 100 million years ago, long before El Hierro blasted into existence.

The findings add new weight to the mantle plume origin for the islands, because the lava fossils suggest that El Hierro is only 2.5 million years old, and thus the youngest volcano in the volcanic chain, the researchers said.

"The sediment seems to fit between these ancient rocks and the actual activity of El Hierro," Troll said. "It tells us there was an ancient volcanic province that went extinct; then, much, much later, the island of El Hierro formed."

Mind the gap

However, the study is unlikely to have a significant impact on current thinking about the origin of the Canary Islands, said Paul van den Bogaard, a geochemist at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany. "El Hierro-South Hierro Ridge has a proven volcanic eruption record ranging from the Early Cretaceous [Period] to the Quaternary [Period]," Van den Bogaard said in an email. "It looks to me like they are making a mountain out of a mole hill, or a seamount out of a coccolithophore, so to speak."

Troll and his students are now collecting similar lava fossils from other Canary Island volcanoes, to document whether the chain becomes younger toward the west. If the plume model is correct, scientists can start to predict how El Hierro volcano will behave in the future, Troll said.

"It will grow up and become an adult, like any other member of its family," he said.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science .