Ancient Earth Had Weird Chemistry: Vanilla Rocks, Lemon-Juice Soil

During the worst mass extinction in Earth's history, acid rain may have at times made the ground as acidic as lemon juice, new research shows.

The mass extinction at the end of the Permian period, about 250 million years ago, was the most extreme die-off in Earth's history. The catastrophe killed as much as 95 percent of ocean species.

The highly level of acidity in the soil at the time of the extinction was revealed in the new study when researchers looked at levels of a compound called vanillin in rocks that date to that time. The chemical is the main ingredient in natural vanilla extract and is also produced when wood decomposes. Normally, bacteria in the soil convert vanillin into vanillic acid, but acidic conditions hinder this process.

The researchers found that the ratios of vanillic acid to vanillin in the rocks show that the level of acidity of the soil at the end of the Permian could have been close to that of vinegar or lemon juice.

"We have used methods from the present-day food industry to work out what happened during an end-Permian food-chain collapse," said lead study author Mark Sephton, a geochemist at Imperial College London in England. [Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions]

That level of acidity suggests that large-scale volcanic eruptions occurred at the time of the extinction, the researchers said. It'sS long been thought that a key factor behind the end-Permian extinction was cataclysmic volcanic activity in what is now Siberia, which spewed out as much as 2.7 million square miles (7 million square kilometers) of lava, an area nearly as large as Australia.

Three-dimensional computer simulations suggest these eruptions would have pumped out gases that led to intense pulses of acid rain. This would have killed off plant life on land, causing a collapse in the food chain and wreaking global havoc. However, until now, researchers lacked direct evidence of this acidification.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

With the new findings, however, "we have the ability to look at the end-Permian event like a crime scene and recognize the chemical fingerprints of the murder weapon," Sephton told Live Science.

That crime scene would have involved acid rain falling on the ancient supercontinent Pangaea as the result of the volcanic eruptions, killing off end-Permian forests and releasing vanillin from their decaying remains. The acidic soils would have prevented bacteria from converting the vanillin to vanillic acid, and as the soil eroded with the demise of the Permian forests, the vanillin and vanillic acid would have washed with sediments into shallow marine waters.

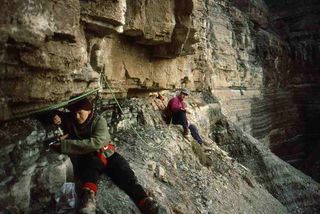

In their research, the scientists investigated marine sediments that were nearly 252 million years old, located in the cliff faces near the village of Vigo Meano in the Southern Alps of northern Italy. These rocks have displayed the most diverse collection of organic compounds seen yet in end-Permian marine sediments.

The findings also suggest that the acidification of the soil occurred not all at once, but rather in repeated pulses of acid rain, the researchers said.

The next step in the research "will be to carry out similar studies on rocks from around the world to confirm the global extent of acidity at the end of the Permian," Sephton said. However, "finding other locations with such well-preserved organic matter may be a challenge," he said.

Sephton and his colleagues will detail their findings in the February issue of the journal Geology.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.