Babies Understand Friendship, Meanies and Bystanders

Babies who are just over a year old already comprehend complex social interactions — they understand what other people know and don't know, and expect them to behave accordingly, new research shows.

In the new study, 13-month-olds who watched a puppet show in which one character witnessed another behaving badly expected the witness to shun the villain. But the babies did not expect a shunning if the villain acted badly when the witness wasn't looking.

Even at this young age, the babies were mostly very intrigued by the drama, said Yuyan Luo a psychologist at the University of Missouri and co-author of the study.

"Almost all babies look really concerned when they see the puppet violence," Luo told Live Science.

Social smarts

In the study, the two characters — call them A and B — interacted in a friendly manner, but then B hit a third character, C.

"Babies think A should do something about it if they see B do something bad," Luo said. [That's Incredible! 9 Brainy Baby Abilities]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Before they can even talk and walk, babies seem to exhibit social savvy, research shows. At around 8 months old, infants like to see wrongdoers punished, and they may develop sympathy for victims of bullying by 10 months of age.

Likewise, even very young babies seem to understand others' perspectives, a talent called "theory of mind." Although researchers once thought that theory of mind did not develop until the preschool years, more-recent studies suggest that it begins to emerge by 7 months to 18 months of age.

Most studies of theory of mind use experiments called "false belief" tasks, in which a baby may watch a person put an item in a hiding place, then leave the room. While the person is away, another experimenter moves the object. The first person then returns and either looks in the original spot or in the new spot.

The researchers test where babies or toddlers expected the person to look. This is done to find whether these youngsters understand that the person should not know that the object has been moved, or, in other words, that he or she has a false belief about the world. In the new study, Luo and her graduate student, You-jung Choi, created a similar false-belief task. This one, however, was about social situations.

Complex interactions

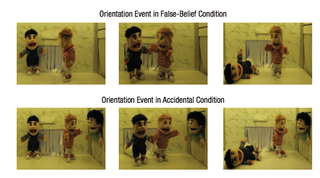

In the experiment's puppet show, Puppet A and Puppet B first interacted in a friendly way, clapping and dancing around one another. Next, Puppet B hit a third puppet, Puppet C. In some cases, Puppet A was standing nearby, watching the bad behavior. In others, Puppet A had left the stage and didn't see the hit.

In a third condition, Puppet B hit Puppet C only by accident. Finally, Puppets A and B reunited, and A was either depicted as playing nicely with B or as shunning B.

A total of 48 13-month-olds watched these shows as researchers tracked how long the babies watched A and B after the hit.

Pre-verbal babies, in general, spend more time looking at things that are unexpected. In this case, Luo and Choi found, the babies stared longer when A acted friendly after seeing B hit C than they did when A shunned B after witnessing the bullying. In other words, the babies seemed to realize that A had seen something bad happen and expected A to respond accordingly.

Babies also stared longer when A shunned B after not seeing the hit.

"Even though baby saw B hit C, baby expected A to play with B again," Choi said. This finding indicates that the babies know what A does — and doesn't — know. They don't expect A to shun B, because they realize that A didn't see B do anything wrong.

Finally, when the hit was accidental, babies looked equally at the A and B interaction, whether or not A shunned B or played nicely. The babies seemed to understand the intentionality of the hit, Luo said, as well as A's knowledge about it.

The study, published online Jan. 28 in the journal Psychological Science, is among the first to examine young babies' responses to complicated social interactions, particularly false beliefs that might arise during social situations. These are talents that help humans navigate the social world as they get older, Choi said.

Now, the researchers are studying how babies react when a character does something nice rather than mean. The scientists also want to research how babies expect witnesses to treat victims.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.