HIV, Syphilis Tests? There's an App for That

There are gizmos that let your smartphone read credit cards, sync with your fitness wristband and even function as a TV remote control. Now you can add "run an HIV test" to the list.

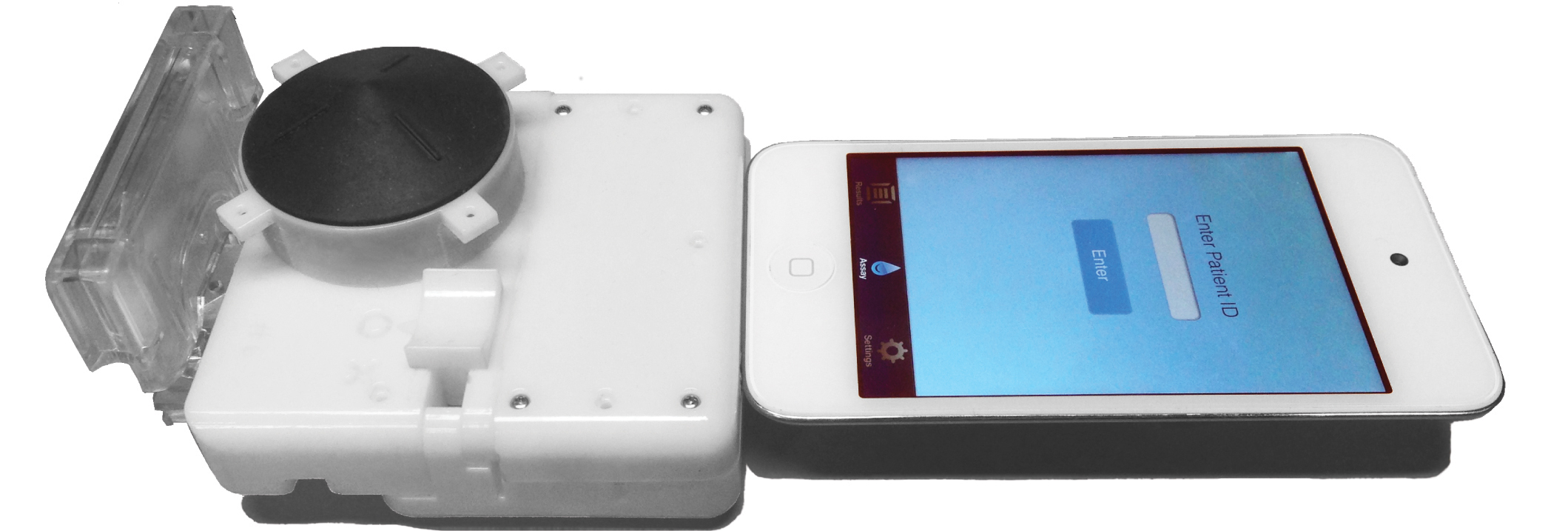

A device invented by biomedical engineers at Columbia University turns a smartphone into a lab that can test human blood for the virus that causes AIDS or the bacteria that cause syphilis. The device is a dongle that attaches to the headphone jack, and requires no separate batteries. An app on the phone reads the results.

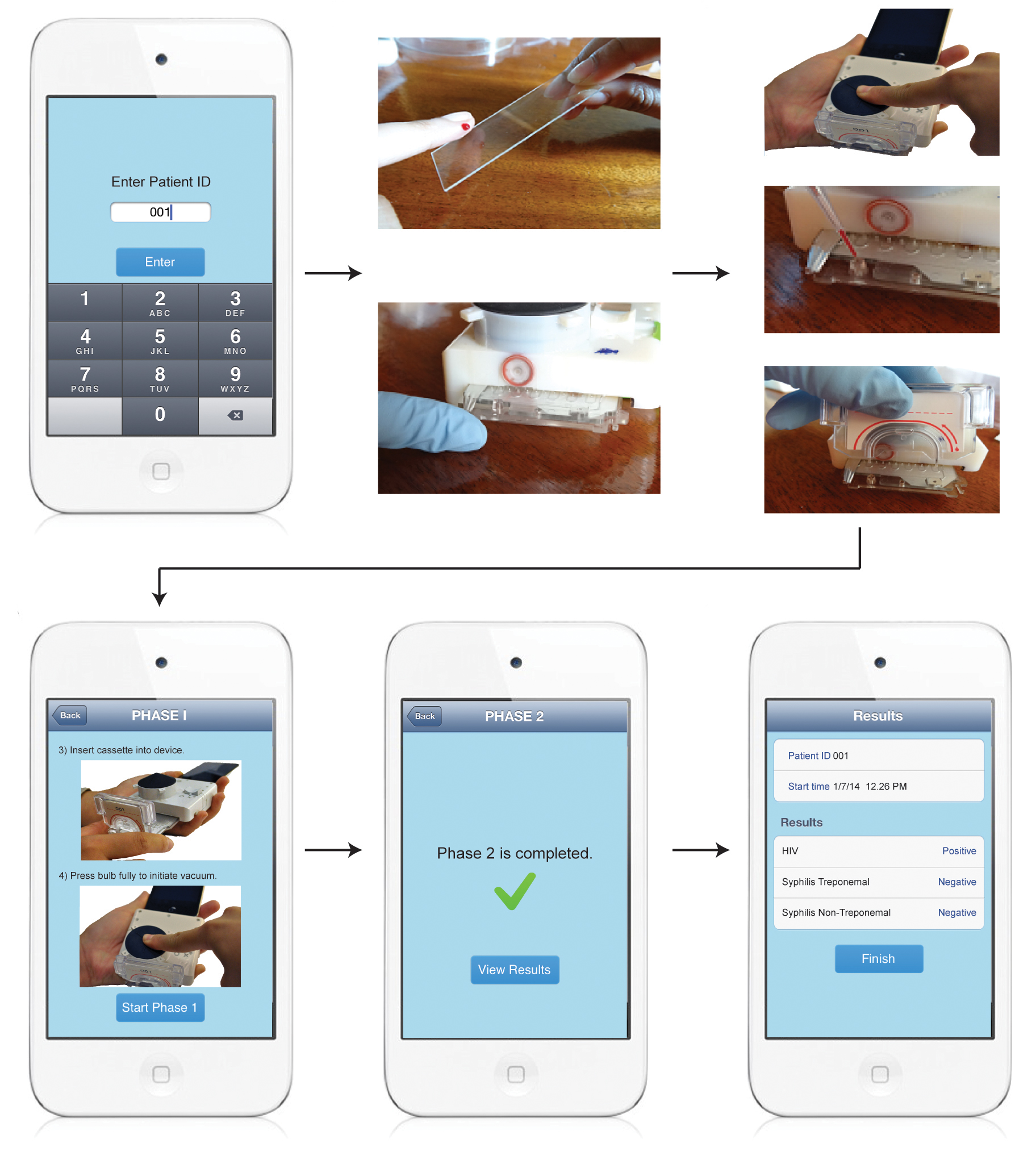

The dongle contains a lab on a chip. It consists of a one-time-use cassette — which has tiny channels as thin as a human hair — and a pump, which is operated by a mechanical button and draws blood from an inlet through the channels.

Once the blood is inside the device, it meets chemicals that react with markers for HIV and syphilis. This kind of test is called an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and is considered one of the best methods for diagnosing diseases, said Samuel Sia, an associate professor of biomedical engineering at Columbia, who led the research. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

The blood changes the color and opacity of the chemicals (formally speaking, the solutions' optical depth changes). Then, LED lights shine through the mixture to a set of photocells, which read the change in the color and opacity and send the data to the app. The whole process takes 15 minutes.

The device requires little power because the pump is hand-activated — the person who wants to conduct the blood test presses a plunger to draw the blood. The current to run the LEDs comes from the phone's audio signal, according the researchers' report of their device, which is published today (Feb. 4) in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

The test results can be read by anyone with little prior training in lab technique necessary, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers got the idea for the device when examining the costs and the logistical difficulties of getting equipment for HIV testing to rural areas or developing countries. Lab-on-a-chip devices have become more common in the last several years, but few are designed for use by people who don't have a lot of trianing, and the devices themselves tend to be expensive and customized.

"People [developing such devices] were not focused on usability," Sia said. "If you have a test that takes 20 steps and a laboratory staff, that's not going to make an impact on society."

Although sophisticated lab technology is scant in the developing world, smartphones are being adopted quickly. The research firm Informa UK projects that the number of smartphone connections, a close proxy for users, in Africa will grow to 204 million in 2015, from 154 million in 2014.

That kind of growth makes smartphones a natural target for the kind of technological development involved in the blood-testing device, the researchers said.

Sia said the device should cost about $34. The equipment normally needed to run an ELISA test usually costs $18,000 or more, and the tests themselves — if one screened or both HIV and syphilis — are on the order of $8.50, according to the paper. To keep costs down in the new method, the cassette is made via injection molding, a process that allows for mass production, and each test would run about $1.44.

The device can also work with an iPod, the researchers noted.

The team tested the device at three clinics in Rwanda, with a total of 96 patients, as part of a screening program to help prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

When looking to see whether patients were infected with HIV or syphilis, the test was able to correctly identify an infection 92 to 100 percent of the time.

The testing device was compared to commercial lab tests and produced 12 false positives for HIV. In testing syphilis, of which there are two types (treponemal and nontreponemal), there were 26 false positives in total and only one false negative. Sia noted that false positives are often caught as the patient goes for further treatment and more-sophisticated testing, and for screening purposes it's generally better to have some false positives and fewer false negatives.

Because there's no need to ship the blood sample to a laboratory, health workers can discuss the results with the patient on the spot. This also removes some of patients' privacy concerns, the researchers said.

The patients also seemed to like a finger prick more than the needle used to draw larger quantities of blood in traditional testing, Sia told Live Science.

The work was funded by a Saving Lives at Birth transition grant and the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation. The team collaborated with a company, OPKO Diagnostics, and two researchers on the team are employees of that company, according to the study.

The paper appears in the Feb. 4 issue of Science Translational Medicine.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.