Waking Beasts: Underwater Volcanoes Roused by Ice Ages

Do fire and ice link up to alter Earth's climate?

The climate-driven rise and fall of sea level during the past million years matches up with valleys and ridges on the seafloor, suggesting ice ages influence underwater volcanic eruptions, two new studies reveal. And because volcanic chains suture some 37,000 miles (59,500 kilometers) of ocean floor, the eruptions could pump out enough carbon dioxide gas to shift planetary temperatures, the study authors suggest.

"Surprisingly, the deep seafloor matters in the long-term climate cycle," said Maya Tolstoy, lead author of one of the studies and a marine geophysicist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, New York.

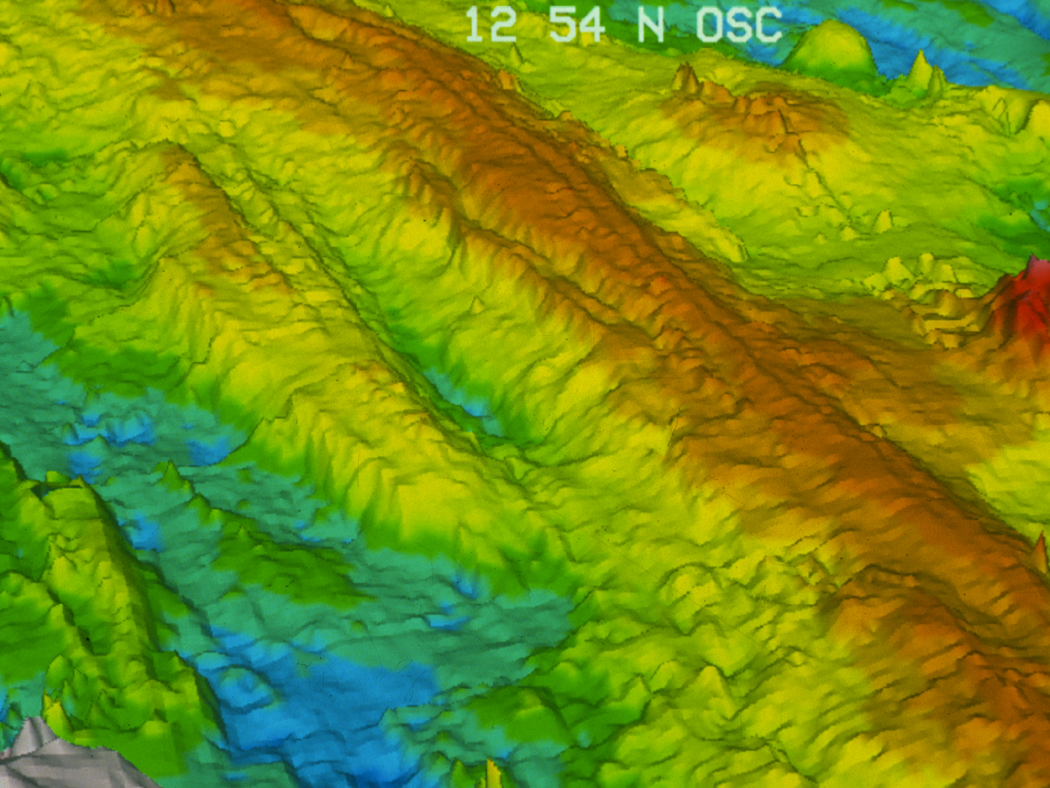

New oceanic crust is born at underwater volcanic chains called spreading ridges, where magma (molten rock) rises to fill the gap between moving tectonic plates. Scientists think that as the plates pull away from spreading ridges, the new crust cools, cracks and sinks, creating gaps between the lines of volcanoes (which are carried away from the ridge with the plate). These parallel volcanic ridges and valleys are some of the most visible features on Earth's ocean floor. [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

Wrinkles in time

Tolstoy's study at the East Pacific Rise spreading ridge, offshore western South America, found connections between ice age cycles and these seafloor corrugations that extend back 800,000 years. The bands of thicker and thinner crust correspond to 100,000-year ice age cycles — the most powerful of Earth's freeze-and-thaw rhythms. When glaciers expanded and sea level dropped, more lava oozed from the ridge volcanoes, Tolstoy discovered. (When magma breaches the surface, it is called lava.) The thinnest crust, formed when eruptions slowed, matches up with eras of higher sea level. The findings were published today (Feb. 5) in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

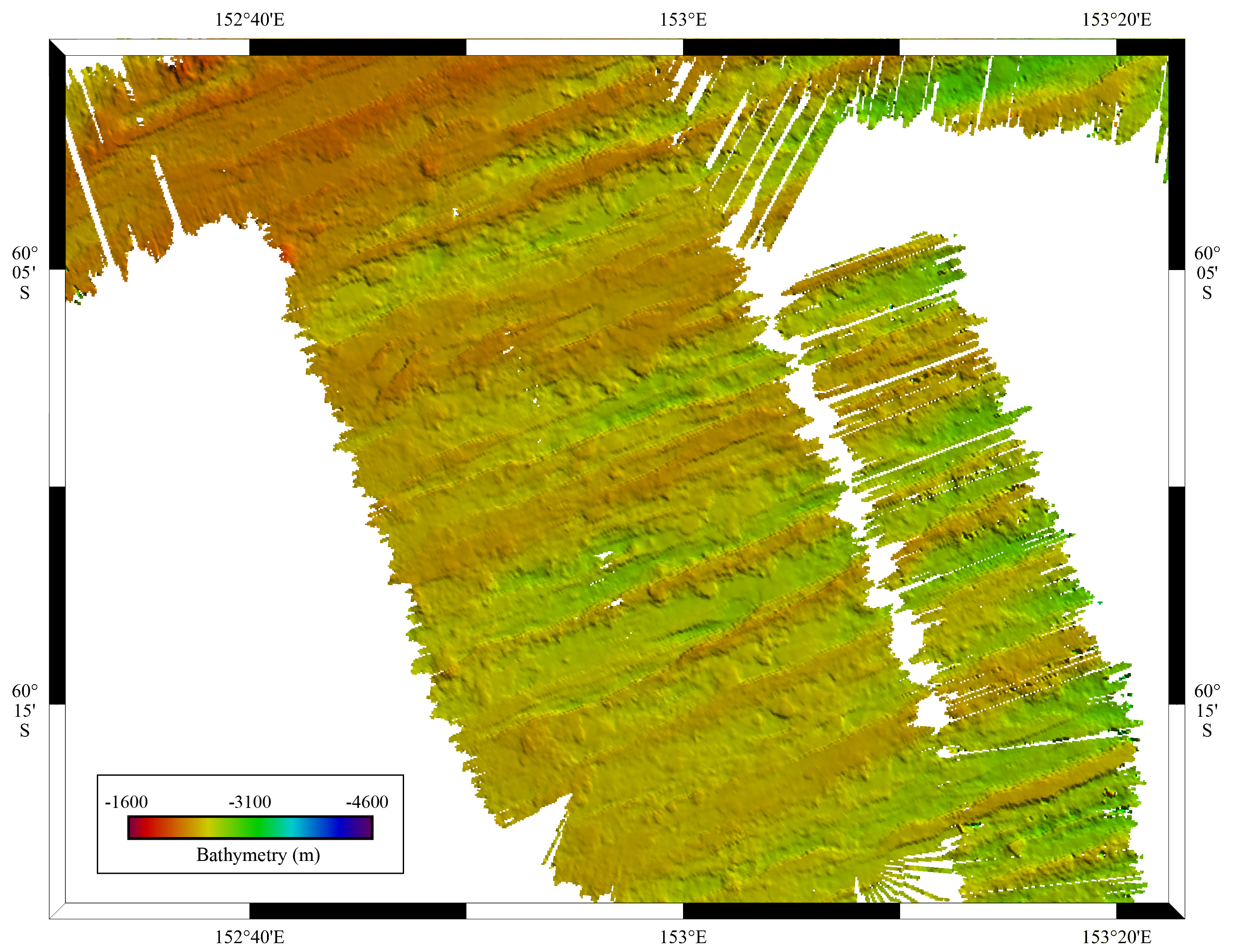

A separate study conducted at the junction between the Australia and Antarctic tectonic plates came up with similar results. For the past million years, when sea level rose, underwater eruptions slowed along the ridge. And when ice sheets expanded and sea level dropped, the lowered ocean pressure boosted volcanic activity, according to a computer model published today in the journal Science. The model suggests that water weight can change how quickly the molten rock, or magma, wells up at spreading ridges.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When ice sheets melt and sea level goes up, it has an effect on volcanoes under the sea," said Richard Katz, co-author of the study in Science and a geophysicist at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom.

Earlier studies have found that volcanoes on land also surged in activity between 12,000 and 7,000 years ago, when ice sheets shrunk after the most recent cold climate swing ended.

Ice ages are driven by regular variations in Earth's orbit. These changes in tilt, eccentricity and orbit create climate cycles that last 23,000 years; 41,000 years; and 100,000 years, respectively (at least for the previous million years). Sea level may rise and fall by some 330 feet (about 100 meters) during these climate swings.

Although eruptions along the Australia-Antarctica spreading ridge and the East Pacific Rise spreading ridge continued whether sea level was high or low, there were pulses of volcanic activity that corresponded to each of these three ice age cycles, both studies reported. The 100,000-year ice age cycle created the most prominent changes in the seafloor crust.

Until now, scientists had assumed that seafloor volcanoes ooze lava at relatively steady rates through time.

Climate converters

Both studies suggest that there could be a complex feedback loop among ice ages, sea level changes and these bursts of volcanic activity. For instance, if volcanoes pick up their pace during an ice age, then carbon dioxide gas could warm the Earth and shrink the ice sheets. (Underwater volcanoes pump carbon dioxide into the ocean, just as their terrestrial cousins add climate-altering gases to the atmosphere.) However, no one knows how much gas would escape into the atmosphere from the oceans. [Fire and Ice: Images of Volcano-Ice Encounters]

"In a broad sense, this reinforces the idea that the climate system and the solid Earth are connected and, in fact, may be thought of as a single system," Katz said. "Not only do ice ages affect volcanism, but volcanism has a feedback effect on climate itself. We haven't proved that yet, but it's a tantalizing possibility."

Tolstoy summarized the results from the East Pacific Rise and from closely monitored submarine eruptions around the world. The findings in Science, led by University of Oxford researcher John Crowley, are based on ocean floor surveys gathered by a Korean icebreaker in 2011 and 2013. Both studies rely on high-resolution spectral imaging of the seafloor, a remote-sensing technique that maps the surface in great detail.

"Both of these data sets have found a signal which is consistent with climate forcing of variations at midocean ridges," said Paul Asimow, a geology professor at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena who was not involved in either study. "Now, apart from showing the effect is there, the other part that needs to be teased out is its consequences."

The authors of each study are now searching for additional ice age signals at other spreading ridges, such as the Juan de Fuca Ridge offshore Washington and Oregon.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science .