Talk about a rodent of unusual size.

The biggest rodent to ever stalk the Earth lived about 3 million years ago in what is now South America — and it used its large front teeth the way today's elephants use their tusks.

The bull-size creature likely used its incisors to root around in the ground for food, possibly even fighting off predators with the sturdy teeth, according to a new study.

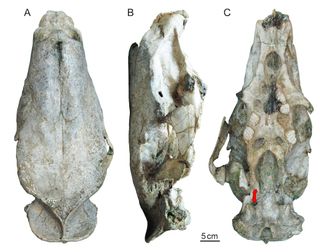

An amateur paleontologist first unearthed the skull of an extinct rodent, Josephoartigasia monesi, from a boulder on a beach in Uruguay. The stunningly well-preserved skull was about 20 inches (51 centimeters) long, suggesting the rodent could grow to 2,200 pounds (1,000 kilograms), the researchers calculated.

For comparison, the next largest rodent ever discovered, Phoberomys, may have weighed up to 1,500 pounds (680 kg). And the modern world's biggest rodent, the capybara, can weigh a modest 130 pounds (60 kg). [Rumor or Reality: The Creatures of Cryptozoology]

These ancient overgrown rodents sported large front teeth, whose exact purpose had remained unclear.

Past studies had suggested the beasts had fairly weak chewing muscles and small grinding teeth. That suggested the animals dined on soft vegetation and fruit. Yet most rodents have tremendously strong bites, and the researchers suspected this massive rodent was no exception.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To understand more about how J. monesi used its teeth, Philip Cox, an archaeologist at Hull York Medical School in England, and his colleagues analyzed the likely orientation and size of the animals' muscles along the jaw.

They estimated the rodent could produce a bite force of about 312 pounds force (1,389 N) — equivalent to that of a tiger. Even more impressive, the force at the animals' incisors, or third molars, could reach about three times that amount, at 936 pounds force (4,165 N).

Because chomping down on veggies wouldn't require that level of force, the authors suspected the incisors had another purpose.

"We concluded that Josephoartigasia must have used its incisors for activities other than biting, such as digging in the ground for food, or defending itself from predators. This is very similar to how a modern-day elephant uses its tusks," Cox said in a statement.

The findings were published Feb. 4 in the Journal of Anatomy.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.